Fungal Infections of the Ear in Immunocompromised Host: a Review

Borlingegowda Viswanatha1 and Khaja Naseeruddin2

11Professor

of ENT, Victoria Hospital, Bangalore Medical College & Research

Institute, Bangalore. INDIA 2Professor of ENT, Joint Director of

Medical Education, Bangalore. INDIA

Correspondence

to: DR.

B. Viswanatha, M.S; DLO., # 716, 10th Cross, 5th Main, M.C. Layout,

Vijayangar, Bangalore - 560, 040 Karnataka, INDIA. Tel: 91-80-23381567

Cell: 91-0-9845942832. E-mail: drbviswanatha@yahoo.co.in

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Published: January 14, 2011

Received: November 09, 2010

Accepted: December 22, 2010

Medit J Hemat Infect Dis 2011, 3: e2011003; DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2011.003

This article is available from: http://www.mjhid.org/article/view/7008

This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of

the

Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Otomycosis

is a fungal infection of the external ear; middle ear and open mastoid

cavity.1 Meyer first described the fungal infection of the external ear

canal in 1884. External ear canal has an ideal warm humid environment

for the proliferation of fungus.2 Although this disease is rarely life

threatening, it can presents a challenging and frustrating situation

for the otologist and patients due to long term treatment and high rate

of recurrence.3 Otomycosis is seen more frequently in immunocompromised

patients as compared to immunocompetent persons. Recurrence rate is

high in immunocompromised patients and they need longer duration

treatment and complications are more frequent in immunocompromised

patients.

In the recent years; opportunistic fungal infections are gaining greater importance in human medicine as a result of possibly huge number of immunocompromised patients.4 In immunocompromised patients, it is important that the treatment of otomycosis be vigorous, to minimize complications such as hearing loss, tympanic membrane perforations and invasive temporal bone infection.5 Fungal cultures are essential to confirm the diagnosis.

Hematological investigations play a very important role in confirming the diagnosis and immunity status of the patients. In diabetic patients with otomycosis, along with antifungal therapy, blood sugar levels should be controlled with medical therapy to prevent complications.

In the recent years; opportunistic fungal infections are gaining greater importance in human medicine as a result of possibly huge number of immunocompromised patients.4 In immunocompromised patients, it is important that the treatment of otomycosis be vigorous, to minimize complications such as hearing loss, tympanic membrane perforations and invasive temporal bone infection.5 Fungal cultures are essential to confirm the diagnosis.

Hematological investigations play a very important role in confirming the diagnosis and immunity status of the patients. In diabetic patients with otomycosis, along with antifungal therapy, blood sugar levels should be controlled with medical therapy to prevent complications.

Introduction

Otomycosis or fungal otitis externa has typically been described as fungal infection of the external auditory canal with infrequent complications involving the middle ear.[3] Fungi causes 10% of all cases of otitis externa.[6] In the recent years there has been an increase in the incidence as a result of possibly huge number of immunocompromised patients. In the past, there were controversies regarding the prevalence and even existence of otomycosis. It is now considered to be a definitive clinical entity and a continuing problem.1 Although there has been controversy with respect to whether the fungi are the true infective agents versus mere colonization of the species as a result of compromised local host immunity secondary to bacterial infection, most clinical and laboratory evidence shows that otomycosis as a true pathological entity.[3]

General cellular immunity is reduced in situations such as diabetes, steroid administration, HIV infection, chemothraphy and malignancy (especially those involving cells of immune system).This makes an immunocompromised host susceptible to fungal infections. Normal bacterial flora is one of the host defense mechanism against fungal infections .This mechanism is altered in patient patients using antibiotics ear drops and cause otomycosis.[2]

Otomycosis is sporadic and caused by a wide variety of fungi, most of which are saprobe occurring in diverse type of environmental material.[4] It affects 10% of the population in their life time.[6] Fungi are abundant in soil or sand which contains decomposing vegetable matter. This is desiccated rapidly in tropical sun and blown in wind as small dust particles. The air borne fungal spores are carried by water vapors, a fact which correlates the higher rates of infection, monsoon when relative humidity rises to 80%.[7] Many studies have shown that the incidence was more common in third decade of life. Higher incidence in young adults may be attributed to the fact that these people are more exposed to the mycelia, whereas extreme age groups are not exposed to the pathogens.[3,8,9,10]

Common symptoms of otomycosis are itching, ear pain, ear discharge, blocking decreased hearing and tinnitus.[3,8,10] The correct diagnosis of otomycosis requires a high index of suspicion, given that the most common presenting symptoms, otalgia and otorrhea, are nonspecific.[5]

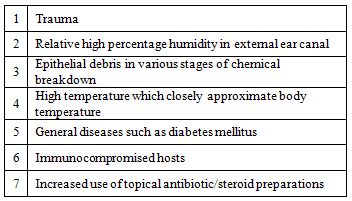

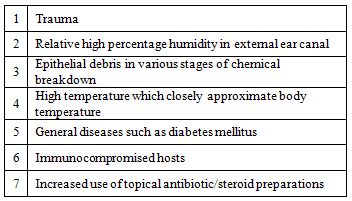

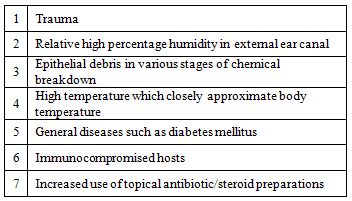

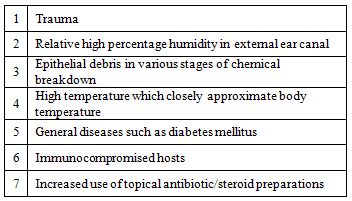

A few conditions may predispose an individual for otomycosis (table 1).[3,11] An immunocompromised host is more susceptible to otomycosis. Patients suffering from diabetes, lymphoma, transplantation patients, patient receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy and AIDS patients, are also at increased risk for potential complications from otomycosis [9].

Table 1: Showing predisposing factors for otomycosis

Ear cleaning habits may also contribute to pathogenesis. Traumatized external ear canal skin can present a favorable condition for fungal growth.[11]Clinical studies have shown that otological procedures, particularly those that result in mastoid cavity, as a potential risk factor for otomycosis.[3] The factors that predisposes to otomycosis in the previously operated ears are;

Pseudallescheria boydii is a saprophytic fungus capable of causing invasive fungal infections in humans, especially in immunocompetent hosts. This fungus is morphologically similar to Aspergillus but is resistant to conventional systemic antifungal therapy with amphotericin B.[14]

Many studies have shown that otomycosis is predominantly unilateral disease in immunocompetent hosts.[8,11,15] In a recent study by Viswanatha et al [13] bilateral involvement was seen more in immunocompromised group than in immunocompetent group.

Fungal cultures are essential to confirm the diagnosis. Hematological investigations play a very important role in confirming the diagnosis and immunity status of the patients. In diabetic patients with otomycosis, blood sugar levels should be controlled with medical therapy to prevent complications due to otomycosis. All the relevant hematological investigations should be done in immunocompromised patients.

Complications of otomycosis includes tympanic membrane perforation, hearing loss and invasive temporal bone infection (table 2).[5,16] Tympanic membrane perforation can occur as a complication of otomycosis that starts in an ear with an intact ear drum.[5] In a clinical study by Ram Kumar,[16] the incidence of tympanic membrane perforation in otomycosis was found to be 11% and perforation was more common with otomycosis caused by Candida albicans. Tympanic membrane perforation is seen more commonly in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent patients.[13] This may be due to the fact that majority of the cases of otomycosis in immunocompromised patients are caused by Candida albicans.[13]

Table 2: Showing complications of otomycosis

Most of the perforations were behind the handle of the malleus. The mechanism of perforation has been attributed to mycotic thrombosis of the tympanic membrane blood vessels resulting in avascular necrosis of tympanic membrane.[5,17] There may not be any clinical features predictive of tympanic membrane perforation. Tympanic membrane involvement is likely a consequence of fungal inoculation in the most medial aspect of the external canal or direct extension of the disease from adjacent skin.[3]

In immunocompromised patients malignant otitis externa can, rarely, present as an aggressive angioinvasive fungal infection of the temporal bone.[2] Invasive Aspergillus otomastoiditis resulting from a tympanogenic source is a rare entity but is being found with increased frequency in immunocompromised hosts. Invasive Aspergillosis is most commonly observed in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, but it may occur in variety of diseases characterized by defective humoral or cell-mediated immunity.[18] Aspergillus and Mucor, have a propensity to invade arterial walls in immunocompromised patients, especially uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, leading to thrombosis and tissue infarction.[19]

Strauss and Fine20 reported two cases of Aspergillus otomastoiditis caused by Aspergillus fumigatus in AIDS patients. Haruna et al [19] reported a case of invasive fungal temporal bone infection caused by Mucor, leading to meningoencephalitis in an immunocompromised patient. Nicolas et al [14] have reported a case of invasive Pseudallescheria boydii fungal infection of the temporal bone in a patent with AIDS.

Treatment of otomycosis includes microscopic suction clearance of fungal mass, discontinuation of topical antibiotics and treatment with antifungal ear drops for three weeks. Ear should be kept dry for three weeks. Small perforations heal spontaneously and larger perforation requires myringoplasty.[13]

Bassouni et al [21] studied the effects of antifungal agents and found that clotrimazole ear drops was more effective antifungal agent in the treatment of otomycosis. According to Stern et al [22] and Jackman et al, [23] clotrimazole ear drops is the most effective antifungal agent. In another study fluconozole ear drops was found to be more effective in treating otomycosis.[24] Clotrimazole and fluconozole ear drops should be used for 3-4 weeks.

Oral and intravenous preparations of antifungal agents are available for severe infections in immunocompromised patients.[2] Oral antifungal are unlikely to succeed in the absence of adequate local care.[3] These antifungal agents should be given for 3-4 weeks depending on the patient’s condition.

Fungal infections of the mastoid cavity of the immunocompromised patients who have undergone canal wall down mastoidectomy are seen quite frequently and they require prolonged treatment with antifungal ear drops and oral antifungal drugs. The recommended treatment for patients suffering from fungal otomastoiditis includes surgical debridement and systemic antifungal therapy with amphotericin B being the gold standard.[14] Antifungal agents should be given for 3-4 weeks depending on the patient’s condition.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of otomycosis in can be really challenging in immunocompromised patients. Recurrences are common in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent patients. Eradication the disease may be difficult in immunocompromised patients, who have undergone canal wall down mastoidectomy. In these patient prolonged antifungal therapy is required.

Otologist should remain alert for otomycosis and should consider obtaining hematological investigations and fungal cultures when this disease is suspected in immunocompromised host.

Otomycosis or fungal otitis externa has typically been described as fungal infection of the external auditory canal with infrequent complications involving the middle ear.[3] Fungi causes 10% of all cases of otitis externa.[6] In the recent years there has been an increase in the incidence as a result of possibly huge number of immunocompromised patients. In the past, there were controversies regarding the prevalence and even existence of otomycosis. It is now considered to be a definitive clinical entity and a continuing problem.1 Although there has been controversy with respect to whether the fungi are the true infective agents versus mere colonization of the species as a result of compromised local host immunity secondary to bacterial infection, most clinical and laboratory evidence shows that otomycosis as a true pathological entity.[3]

General cellular immunity is reduced in situations such as diabetes, steroid administration, HIV infection, chemothraphy and malignancy (especially those involving cells of immune system).This makes an immunocompromised host susceptible to fungal infections. Normal bacterial flora is one of the host defense mechanism against fungal infections .This mechanism is altered in patient patients using antibiotics ear drops and cause otomycosis.[2]

Otomycosis is sporadic and caused by a wide variety of fungi, most of which are saprobe occurring in diverse type of environmental material.[4] It affects 10% of the population in their life time.[6] Fungi are abundant in soil or sand which contains decomposing vegetable matter. This is desiccated rapidly in tropical sun and blown in wind as small dust particles. The air borne fungal spores are carried by water vapors, a fact which correlates the higher rates of infection, monsoon when relative humidity rises to 80%.[7] Many studies have shown that the incidence was more common in third decade of life. Higher incidence in young adults may be attributed to the fact that these people are more exposed to the mycelia, whereas extreme age groups are not exposed to the pathogens.[3,8,9,10]

Common symptoms of otomycosis are itching, ear pain, ear discharge, blocking decreased hearing and tinnitus.[3,8,10] The correct diagnosis of otomycosis requires a high index of suspicion, given that the most common presenting symptoms, otalgia and otorrhea, are nonspecific.[5]

A few conditions may predispose an individual for otomycosis (table 1).[3,11] An immunocompromised host is more susceptible to otomycosis. Patients suffering from diabetes, lymphoma, transplantation patients, patient receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy and AIDS patients, are also at increased risk for potential complications from otomycosis [9].

Table 1: Showing predisposing factors for otomycosis

Ear cleaning habits may also contribute to pathogenesis. Traumatized external ear canal skin can present a favorable condition for fungal growth.[11]Clinical studies have shown that otological procedures, particularly those that result in mastoid cavity, as a potential risk factor for otomycosis.[3] The factors that predisposes to otomycosis in the previously operated ears are;

- Recurrent drainage, antibiotic/antifungal applications – this may alter the local environment of the external ear canal and allow super infection by nasocomial fungi.

- Alteration in the anatomy by canal wall down procedures may also produce changes in the cerumen production or relative humidity that favor fungal growth.[3]

Pseudallescheria boydii is a saprophytic fungus capable of causing invasive fungal infections in humans, especially in immunocompetent hosts. This fungus is morphologically similar to Aspergillus but is resistant to conventional systemic antifungal therapy with amphotericin B.[14]

Many studies have shown that otomycosis is predominantly unilateral disease in immunocompetent hosts.[8,11,15] In a recent study by Viswanatha et al [13] bilateral involvement was seen more in immunocompromised group than in immunocompetent group.

Fungal cultures are essential to confirm the diagnosis. Hematological investigations play a very important role in confirming the diagnosis and immunity status of the patients. In diabetic patients with otomycosis, blood sugar levels should be controlled with medical therapy to prevent complications due to otomycosis. All the relevant hematological investigations should be done in immunocompromised patients.

Complications of otomycosis includes tympanic membrane perforation, hearing loss and invasive temporal bone infection (table 2).[5,16] Tympanic membrane perforation can occur as a complication of otomycosis that starts in an ear with an intact ear drum.[5] In a clinical study by Ram Kumar,[16] the incidence of tympanic membrane perforation in otomycosis was found to be 11% and perforation was more common with otomycosis caused by Candida albicans. Tympanic membrane perforation is seen more commonly in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent patients.[13] This may be due to the fact that majority of the cases of otomycosis in immunocompromised patients are caused by Candida albicans.[13]

Table 2: Showing complications of otomycosis

Most of the perforations were behind the handle of the malleus. The mechanism of perforation has been attributed to mycotic thrombosis of the tympanic membrane blood vessels resulting in avascular necrosis of tympanic membrane.[5,17] There may not be any clinical features predictive of tympanic membrane perforation. Tympanic membrane involvement is likely a consequence of fungal inoculation in the most medial aspect of the external canal or direct extension of the disease from adjacent skin.[3]

In immunocompromised patients malignant otitis externa can, rarely, present as an aggressive angioinvasive fungal infection of the temporal bone.[2] Invasive Aspergillus otomastoiditis resulting from a tympanogenic source is a rare entity but is being found with increased frequency in immunocompromised hosts. Invasive Aspergillosis is most commonly observed in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, but it may occur in variety of diseases characterized by defective humoral or cell-mediated immunity.[18] Aspergillus and Mucor, have a propensity to invade arterial walls in immunocompromised patients, especially uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, leading to thrombosis and tissue infarction.[19]

Strauss and Fine20 reported two cases of Aspergillus otomastoiditis caused by Aspergillus fumigatus in AIDS patients. Haruna et al [19] reported a case of invasive fungal temporal bone infection caused by Mucor, leading to meningoencephalitis in an immunocompromised patient. Nicolas et al [14] have reported a case of invasive Pseudallescheria boydii fungal infection of the temporal bone in a patent with AIDS.

Treatment of otomycosis includes microscopic suction clearance of fungal mass, discontinuation of topical antibiotics and treatment with antifungal ear drops for three weeks. Ear should be kept dry for three weeks. Small perforations heal spontaneously and larger perforation requires myringoplasty.[13]

Bassouni et al [21] studied the effects of antifungal agents and found that clotrimazole ear drops was more effective antifungal agent in the treatment of otomycosis. According to Stern et al [22] and Jackman et al, [23] clotrimazole ear drops is the most effective antifungal agent. In another study fluconozole ear drops was found to be more effective in treating otomycosis.[24] Clotrimazole and fluconozole ear drops should be used for 3-4 weeks.

Oral and intravenous preparations of antifungal agents are available for severe infections in immunocompromised patients.[2] Oral antifungal are unlikely to succeed in the absence of adequate local care.[3] These antifungal agents should be given for 3-4 weeks depending on the patient’s condition.

Fungal infections of the mastoid cavity of the immunocompromised patients who have undergone canal wall down mastoidectomy are seen quite frequently and they require prolonged treatment with antifungal ear drops and oral antifungal drugs. The recommended treatment for patients suffering from fungal otomastoiditis includes surgical debridement and systemic antifungal therapy with amphotericin B being the gold standard.[14] Antifungal agents should be given for 3-4 weeks depending on the patient’s condition.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of otomycosis in can be really challenging in immunocompromised patients. Recurrences are common in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent patients. Eradication the disease may be difficult in immunocompromised patients, who have undergone canal wall down mastoidectomy. In these patient prolonged antifungal therapy is required.

Otologist should remain alert for otomycosis and should consider obtaining hematological investigations and fungal cultures when this disease is suspected in immunocompromised host.

References

- Pradhan B, Tuladhar NR, Amatya RM.

Prevalence of otomycosis in outpatient department of otolaryngology in

Tribhuvan university teaching hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. Ann Otol

Rhinol Laryngol 112:2003; 384-387

- Thrasher RD, Kingdom TT. Fungal infections

of the head and neck: an update. Otolaryngol Cli N Am 36:2003; 577-594.

doi:10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00029-X

- Ho T, Vrabec JT, Yoo D. Otomycosis

:Clinical features and treatment implications. Otolaryngology-Head and

neck surgery 2006;135: 787-791. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.07.008

PMid:17071313

- Jadhav VJ, Pai M, Mishra GS. Etiological

significance of Candida albicans in otitis externa. Mycopathologica

2003;156:313-315. doi:10.1023/B:MYCO.0000003574.89032.99

PMid:14682457

- Rutt AL, Sataloff RT. Aspergillus

otomycosis in an immunocompromised patient. Ear Nose Throat journal

2008; 87:622-623

- Carney AS. Otitis externa and otomycosis is Scott Brown’s Otolaryngology, Head and neck surgery.Eds: Gleeson M, Browning GG, Burton MJ et al. Vol 3,7th edition, Edward Arnold publication, Great Britain, 2008

- Beaney GPE, Broughton A. Tropical otomycosis. Journal of laryngology and otology 1967; 81:987-989. doi:10.1017/S0022215100067955

- Paulose KO, Al-Khalifa S, Shenoy P, Sharma

RK. Mycotic infections of the ear (otomycosis):A propective study.

Journal of laryngology and otology 1989; 103 : 30-35. doi:10.1017/S0022215100107960

- Chander J, Maini S, Subrahmanyan S, Handa

A. Otomycosis-a clinico-mycological study and efficacy of mercurochrome

in its treatment. Mycopathologica 1996; 135:9-12. doi:10.1007/BF00436569 PMid:9008878

- Mohanty JC, Mohanty SK, Sahoo RC et al.

Clinico-microbial profile of otomycosis in Berhampur. India journal of

otology 1999; 5:81-83

- Yassin A, Maher A, Mowad MK. Otomycosis: A

survey in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Journal of laryngology

and otology 1978; 92:869-876. doi:10.1017/S0022215100086242

- Prasad KC, Bojwani KM, Shenoy V, Prasad

SC. HIV manifestations in otolaryngology. Am J Otolaryngol 2006; 27:

179 – 185. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.09.011PMid:16647982

- Viswanatha.B, Sumatha D, Vijayashree MS. A comparative study of otomycosis in immune competent and immunocompromised patients. Accepted for publication in Ear nose & throat journal (2009)

- Busaba YN, Poulin M. Invasive

pseudallescheria boydii fungal infection of the temporal

bone.Otolaryngology-Head and neck surgery 1997; 117:

S91-S94

- Yehia MM, Al-Habib HM, Shehab NM.

Otomycosis-A common problem in North Iraq. Journal of laryngology and

otology 1990; 104:387-389. doi:10.1017/S0022215100158529

- Kumar KR. Silent perforation of tympanic membrane and otomycosis. Indian journal of otolaryngology1984; 36.No 4:161-162

- Stern JC, Lucente FE. Otomycosis. Ear Nose

Throat journal 1988:67 :804-5,809-810. PMid:3073938

- Lyos AT, Malpica A, Estrada R, Katz CD,

Jenkins HA. Invasive Aspergillosis of the temporal bone: an unusual

manifestation of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Otolaryngol

1993; 14:444-448. doi:10.1016/0196-0709(93)90121-M

- Haruna S, Haruna Y, Schachern PA, Morizono

T, Paparella MM. Histopathogy update: otomycosis. Am J Otolaryngol

1994; 15:74 -78. doi:10.1016/0196-0709(94)90045-0

- Strauss M, Fine E. Aspegillus

otomastoiditis in aduired immunedeficiency syndrome. Am J Otol

1991;12:49-53. PMid:2012190

- Bassiouny A, Kamel T, Moawad MK, Hindavy

DS. Broad spectrum antifungal agents in otomycosis. Journal of

laryngology and otology 1986; 100: 867-873. doi:10.1017/S0022215100100246

- Stern JC, Shah MK, Lucente FE. In vitro

effectiveness of 13 agents in otomycosis and review of

literature.Laryngoscope 1988;98:1173-1177. doi:10.1288/00005537-198811000-00005.

PMid:3054372

- Jackman A, Ward R, Apri M, Bent J. Topical

antibiotic induced otomycosis. International journal of pediatric

otorhinolaryngology 2005;69:857-860. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.01.022.

PMid:15885342

- Yadav SPS, Gulia JS, Jagat S, Goel AK, Aggarwal N. Role of ototopical fluconozole and clotrimazole in management of otomycosis. Indian journal of otology 2007:13; 12-15