Vincenzo Accurso1, Marco Santoro2*, Salvatrice Mancuso1, Angelo Davide Contrino1, Paolo Casimiro1, Mariano Sardo1, Simona Raso2, Florinda Di Piazza3, Alessandro Perez3, Marco Bono3, Antonio Russo3 and Sergio Siragusa1.

1

Hematology Division University Hospital Policlinico "Paolo Giaccone",

Via del Vespro 129, 90127, Palermo, Italy, Via del Vespro 129, 90127,

Palermo, Italy.

2 Dept. of Surgical, Oncological and

Stomatological Disciplines, University of Palermo, Via del Vespro 129,

90127, Palermo, Italy.

3 Department of Surgical,

Oncological and Stomatological Disciplines, Section of Medical

Oncology, University of Palermo, Via del Vespro 129, 90127, Palermo,

Italy.

Corresponding

author: Vincenzo Accurso. Hematology Division University of

Palermo, Via del Vespro 129, 90127, Palermo, Italy, +393338963096.

E-mail:

casteldaccia@tiscali.it

Published: January 1, 2020

Received: September 8, 2019

Accepted: December 16, 2019

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12(1): e2020008 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2020.008

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Thromboembolic

and bleeding events pose a severe risk for patients with Polycythemia

Vera (PV) and Essential Thrombocythemia (ET). Many factors can

contribute to promoting the thrombotic event due to the interaction

between platelets, leukocytes, and endothelium alterations. Moreover, a

significant role can be played by cardiovascular risk factors (CV.R)

such as cigarette smoking habits, hypertension, diabetes, obesity and

dyslipidemia. In this study, we evaluated the impact that CV.R plays on

thrombotic risk and survival in patients with PV and ET.

|

Introduction

Diagnosis

of PV requires as major criteria, the increase of hemoglobin/hematocrit

ratio, whose threshold levels have been established by 2016 World

Health Organization (WHO) revised criteria (>16.5 g/dL or >49%

for males and >16 g/dL or >48% for females), the presence of JAK2

mutation, the bone marrow tri‐lineage proliferation with Pleomorphic

mature megakaryocytes, and in the absence of a major criterium the

presence of one minor.[1,2] Almost all patients with

PV harbor a JAK2 mutation; approximately 96% and 3% of them display

somatic activating mutations in exon 14 (JAK2-V617F) and JAK2 exon 12,

respectively. Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a chronic

myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) characterized by persistently high

platelet count and overall favorable prognosis with respect to the

other MPNs (but Life-expectancy in ET is inferior to the control

population).[2] Approximately 90% of patients with ET

show a mutually exclusive JAK2, CALR, or myeloproliferative leukemia

(MPL) mutation. In a recently published study conducted on 826 Mayo

Clinic patients with ET, PV, or PMF, the respective median survivals

were approximately 20 years for ET, 14 years for PV, and 6 years for

primary myelofibrosis.[3] The increased risk of

vascular complications over time is the main clinical feature of PV and

ET. Concerning PV, two risk categories are defined. In particular, a

low and high risk has been considered for patients without a history of

thrombosis and younger than 60 years, and patients aged older than 60

or with a history of thrombosis. In ET, four risk categories are

considered: very low (age ≤ 60 years, no thrombosis history, JAK2

wild-type), low (same as very low but presence of a JAK2 mutation),

intermediate (age > 60 years, no thrombosis history, JAK2 wild-type)

and high (thrombosis history present or age > 60 years with JAK2

mutation).[4] Current classifications of the

thrombotic risk in patients with PV, as well as in those with ET do not

predict cardiovascular risk (CVR), and this condition does not

currently influence the choice of cytoreductive therapy. In this study,

we considered evaluating the frequency of CVR in a cohort of patients

with ET and with PV and the possible impact on the thrombotic risk on

survival. This study was approved by our hospital's ethics committee.

Methods

From

January 1997 to May 2019, 403 consecutive patients were followed with a

median follow-up of 48,43 months (0.3 – 316 months). In particular, PV

patients (n.165) had a median follow-up of 58,18 months (0.3 – 289.30

months), while the ET patients (n. 238) had a median follow-up of 44.60

months (0.4 - 316 months). We evaluated, with retrospective analysis,

at diagnosis, the main characteristics of the study population such as

gender, age, and mutational status along with CVR factors frequency

such as cigarette smoking habits, hypertension, diabetes, obesity and

dyslipidemia. In particular, patients with only one of these conditions

were distinguished by those with more than one cardiovascular risk

factor or without CVR factors. Moreover, the correlation of these

cardiovascular risk conditions with the onset of thrombosis has been

evaluated. The frequencies were calculated by using the chi-square

method, and the comparison between medians was evaluated through the

Kruskal-Wallis test. Furthermore, the survival has been evaluated by

the Kaplan and Meyer method and the comparison between survival curves

with the log-rank test.

Results

The

main features, including sex, median age, and the mutational status,

along with the cardiovascular risk factors of the cohort under

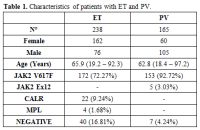

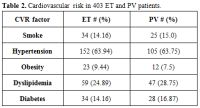

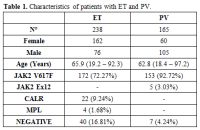

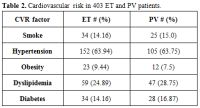

examination (n. 403) were, respectively, summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

In particular, 59 patients with ET (24.79%) and 37 PV patients (22.42)

have no CVR, while 93 ET patients (39.07%) show only one CVR factor and

85 (35.71%) have more than one. Furthermore, 66 PV patients (49%) have

only one cardiovascular risk factor, while 62 (37.57%) have more than

one CVR.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with ET and PV. |

|

Table 2.Cardiovascular risk in 403 ET and PV patients. |

In

patients with PV, we highlighted 49 (29.69%) cases of thrombosis at

diagnosis or before diagnosis and 16 (9.69%) cases of thrombosis after

diagnosis, while in patients with ET, respectively 49 (20.61%) and 17

cases (6.72%). Overall, PV patients show a thrombosis frequency of

39.39% if compared to 27.39% of ET patients (p = 0.014).

In

patients with PV and ET, the frequency of thrombotic episodes is

strictly correlated with cardiovascular risk factors; in fact, the

frequency of thrombosis is much lower in patients without CVR. In ET

patients without CVR, the thrombotic event is present in 10/59 cases if

compared to patients with only one CVR factor (18/93) and to patients

with more than one CVR factor (37/85). In PV patients, thrombosis is

present, respectively, in 11/37 cases, 20/66 cases and 24/62 cases. Our

data also show a significant correlation between cardiovascular risk

factors and survival both in the cohort of patients with PV and ET,

distinguished by the number of cardiovascular risk factors (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Survival and CVR factors in PV (A) and ET (B) patients. |

Discussion

Patients

with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have an increased risk of

thrombotic events if compared with the general population, adding the

latter a higher risk of morbidity and mortality MPNs-associated.[5,6]

A recent single-center study conducted on 526 patients with MPNs with

an overall study period of 3497.4 years, reported an incidence rate of

1.7% of venous thrombosis per patient/year.[7]

Overall, 38.4% of all venous thrombosis occurred before or at diagnosis

of MPNs, with 55.6% occurring at uncommon sites such as splanchnic or

cerebral veins. Polycythemia Vera (PV) and Essential Thrombocythemia

(ET) are myeloproliferative neoplasms respectively characterized by

erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis; other clinical features include

leukocytosis, splenomegaly, thrombosis, bleeding, microcirculatory

symptoms, pruritus, and risk of leukemic or fibrotic transformation;

moreover, thrombosis and cardiovascular disease are more prevalent in

PV than in the other MPNs. It has been estimated that 30% to 50% of PV

patients have minor and major thrombotic complications, and vascular

mortality accounts for 35% to 45% of all deaths.[8]

Also, in ET, thrombotic complications and cardiovascular events are

very frequent. In a recent study, thrombotic events before or at the

time of ET diagnosis were reported in 231 (17.8%) of 1,297 patients.[9]

Determining the thrombotic risk in the PV and ET is pivotal for the

proper therapeutic choice. In PV, two risk categories are generally

considered: high risk (age > 60 years or thrombosis history present)

and low risk (absence of both risk factors). The IPSETt classification

of the thrombotic risk contemplates the assignment of 2 points for

previous thrombotic events in patients aged greater than 60 years and

the presence of JAK2-V617F mutation, 1 point for age greater than 60

years and a point for the presence of CVR factors. The low-risk is

defined by a score lower than 2, the intermediate-risk by a score equal

to 2 and the high-risk by a score greater than 2.[10]

A new classification for the thrombotic risk describes four risk

categories: very low, low, intermediate and high (as described in the

introduction) but, unfortunately, cardiovascular risk factors are not

yet considered. In a previously proposed thrombotic risk classification

model, at the traditional high and low risk category was added an

intermediate risk category specific for all the patients aged under 60

years, with no history of thrombosis but with the presence of

cardiovascular risk factors.[11] This thrombotic risk

classification model was not followed. Cerquozzi et al. explored the

association of cardiovascular risk factors with the occurrence of

arterial or venous events at or following diagnosis; they found that

older age (≥ 60 years), hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and

normal karyotype were associated with arterial events, whereas younger

age (< 60 years), female sex, palpable splenomegaly, and history of

major hemorrhage were associated with venous events.[12]

Today for patients with PV or ET with less than 60 years and with one

or more cardiovascular risk factors, there is no indication for

cytoreductive therapy, but only for antiplatelet drugs prophylaxis.

Only for ET, the IPSET-thrombosis system that includes age, previous

thrombosis, cardiovascular risk factors, and JAK2-V617F mutation is the

recommended prognostic system, and it should be scored in all patients

at diagnosis. This implies that general risk factors for thrombosis,

including smoking habits, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and

hypercholesterolemia, should also be considered even if the absence of

specific therapeutic indications remains.[13]

According to our experience, it should be useful to carry out

prospective studies for the characterization of the influence of

cardiovascular risk factors in the thrombotic event and on survival in

order to evaluate the opportunity to develop specific therapeutic

recommendations for patients with PV and ET with less than 60 years and

cardiovascular risk factors.

References

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016

revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid

neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391-2405. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544 PMid:27069254

- Tefferi

A, Barbui T. Polycytemia vera and essential thrombocythemia:2019 update

on diagnosis,risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2019

Jan;94(1): 133-143. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25303 PMid:30281843

- Tefferi

A, Guglielmelli P, Larson DR, et al. Long-term survival and blast

transformation in molecularly annotated essential thrombocythemia,

polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis. Blood 2014;124:2507-2513; https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-579136 PMid:25037629 PMCid:PMC4199952

- Mahnur

Haider, Naseema Gangat, Terra Lasho, Ahmed K. Abou Hussein, Yoseph C.

Elala, Curtis Hanson,and Ayalew Tefferi .Validation of the revised

international prognostic score of thrombosis for essential

thrombocythemia (IPSET- thrombosis) in 585 Mayo clinic patients.

American Journal of Hematology, Vol. 91, No. 4, April 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24293 PMid:26799697

- Barbui T, Finazzi G, Falanga A (2013) Myeloproliferative neoplasms and thrombosis. Blood 122:2176-2284. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-03-460154 PMid:23823316

- Marchioli

R.,Finazzi G,Landolfi R.,et al.Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large

cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23 (10):

2224-2232 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062 PMid:15710945

- Wille

K, Sadjadian P, Becker T, Kolatzki V, Horstmann A, Fuchs C,Griesshammer

M (2018) High risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in

BCR-ABL-negative myeloproli ferative neoplasms after termination of

anticoagulation. Ann Hematol 98:93-100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-018-3483-6 PMid:30155552

- Vannucchi

AM (2010) Insights into the pathogenesis and management of thrombosis

in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Intern Emerg Med

5:177-184 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-009-0319-3 PMid:19789961

- Andriani

A., Latagliata R.,et al.Spleen enlargement is a risk factor for

thrombosis in essential thrombocythemia: Evaluation on 1,297 patients.

American Journal of Hematology, Vol. 91, No. 3, March 2016 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24269 PMid:26748894

- Barbui

T, Finazzi G, Carobbio A,et al. Development and validation a

international Prognostic Score of thrombosis in World Health

Organization essential thrombocythemia Blood 2012 120: 5128-5133 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-07-444067 PMid:23033268

- Finazzi G.Barbui T. Risk-adapted therapy in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera.Blood Reviews (2005) 19, 243-252 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2005.01.001 PMid:15963833

- Cerquozzi

S, Barraco D,et al (2017) Risk factors for arterial versus venous

thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587

patients. Blood Cancer J 7:662 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6 PMid:29282357 PMCid:PMC5802551

- Barbui

T.,Tefferi A.Vannucchi A.M.,et al Philadelphia chromosome-negative

classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management

recommendations from European LeukemiaNet Leukemia. 2018 May; 32(5):

1057-1069 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1 PMid:29515238 PMCid:PMC5986069

[TOP]