Management of HBV Infection During Immunosuppressive Treatment

Alfredo Marzano

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, San Giovanni Battista Hospital, Turin, Italy

Correspondence

to: Alfredo Marzano, Division of Gastroenterology, AOU San

Giovanni Battista, Corso Bramante 88, 10125, Torino. E-mail: alfredomarzano@yahoo.it

Published: December 22, 2009

Received: December 17, 2009

Accepted: December 21, 2009

Medit J Hemat Infect Dis 2009, 1(3): e2009025 DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2009.025

This article is available from: http://www.mjhid.org/article/view/5226

This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

The

literature on hepatitis B virus (HBV) in immunocompromised patients is

heterogeneous and refers mainly to the pre-antivirals era. Currently, a

rational approach to the problem of hepatitis B in these patients

provides for: a) the evaluation of HBV markers and of liver condition

in all subjects starting immunosuppressive therapies (baseline), b) the

treatment with antivirals (therapy) of active carriers, c) the

pre-emptive use of antivirals (prophylaxis) in inactive carriers,

especially if they are undergoing immunosuppressive therapies judged to

be at high risk, d) the biochemical and HBsAg monitoring (or universal

prophylaxis in case of high risk immunosuppression, as in

onco-haematologic patients and bone marrow transplantation) in subjects

with markers of previous contact with HBV (HBsAg-negative and

antiHBc-positive), in order to prevent reverse seroconversion. Moreover

in solid organ transplants it is suggested a strict adherence to the

criteria of allocation based on the virological characteristics of both

recipients and donors and the universal prophylaxis or therapy with

nucleos(t)ides analogs

Introduction: Hepatitis

B virus infection is a major public and medical concern. Two billion

people are overt carriers of HBV worldwide; of them, 360 million suffer

from chronic HBV infection and over 520,000 die each year, 50,000 from

acute hepatitis B and 470,000 from cirrhosis or liver cancer. Moreover

many subjects have only markers of previous contact with the HBV

(antiHBc+/- antiHBs), which can indicate an Occult HBV Infection (OBI).

Immunodepression due to the underlying disease or to drugs used in immunosuppressive, anticancer therapy and in organ transplants can influence the hepatitis B virus (HBV), both in terms of reactivation and in terms of the acceleration of a pre-existing chronic hepatitis. In this situation the possibility of HBV relapse has been known for years, with clinical manifestations ranging from selflimiting anicteric to fulminant forms or to chronic hepatitis with an accelerated clinical course towards liver decompensation. Hepatitis reacti-vation may influence the continuation of the specific treatments and the survival of immuno-depressed or transplanted patients[1].

The risk of clinical events is mainly observed in overt carriers of HBV, but can also develop in the OBI condition which has been widely described in the literature of the last decade.[2]

Progress in the diagnostic procedures of the various virological conditions associated with HBV, the recent availability of effective antiviral treatments, the growing incidence of immunocompromised patients attributable to the evolution of immunosuppressive therapies and organ transplants and the expectation of an important future increase of HBV reactivation have brought this problem to the fore, although the rational approach and management of these patients is still debated.

Definitions

Virological characteristics: Persistent HBV infection is defined as overt when the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is present in amounts well-detectable by sensitive immune assays and occult in HBsAg-negative subjects with evidence of intrahepatic and/or serum HBV DNA.[2] In occult carriers, HBsAg can be completely absent (real OBI) or undetectable for very low amounts or polymorphisms (false OBI).

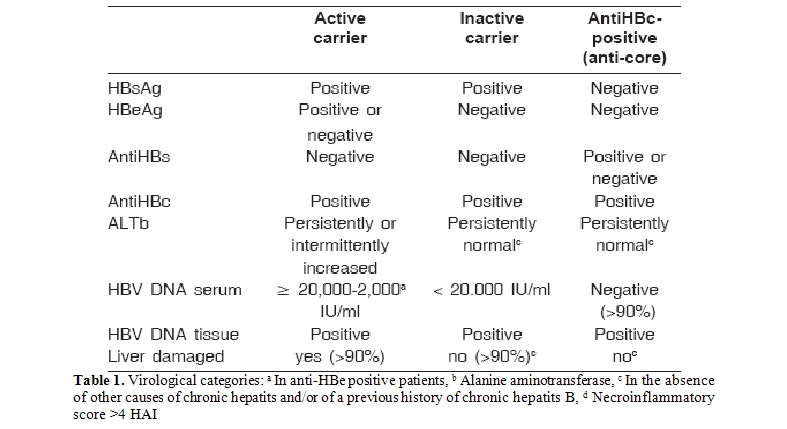

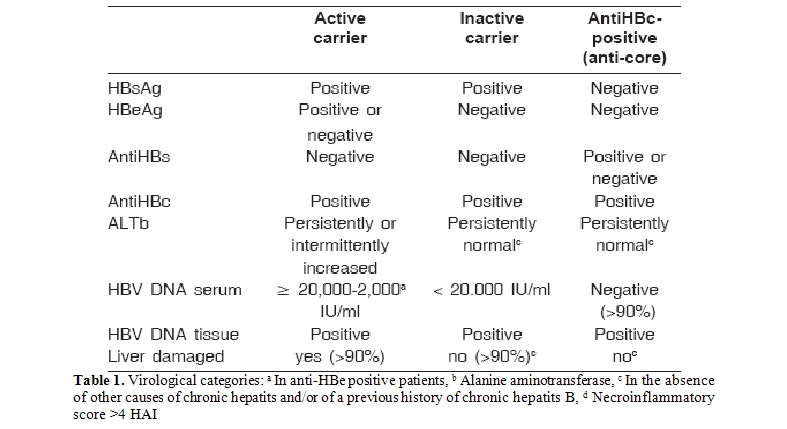

Virological events: In HBV carriers (occult or overt) the following virological events are considered significant: 1) in anti-core subjects the reemergence of HBsAg(sero-reversion), 2) in inactive carriers the appearance of a significant viremia (≥20,000 IU/ml) (reactivation), as this is frequently associated with liver damage due to HBV, 3) in active carriers the persistence of a significant viremia (> 20,000 IU/ml in HBeAg positive patients and > 2,000 IU/ml in HBeAg negative subjects) (activity), as this is frequently associated with progression of liver damage due to HBV, 4) in all the virological categories (whether or not during prophylaxis or therapy with antivirals), the increase in at least one logarithm of HBV DNA, compared to its nadir, reconfermed in two consecutive serum tests during monitoring (virologic breakthrough) (Table 1)[4].

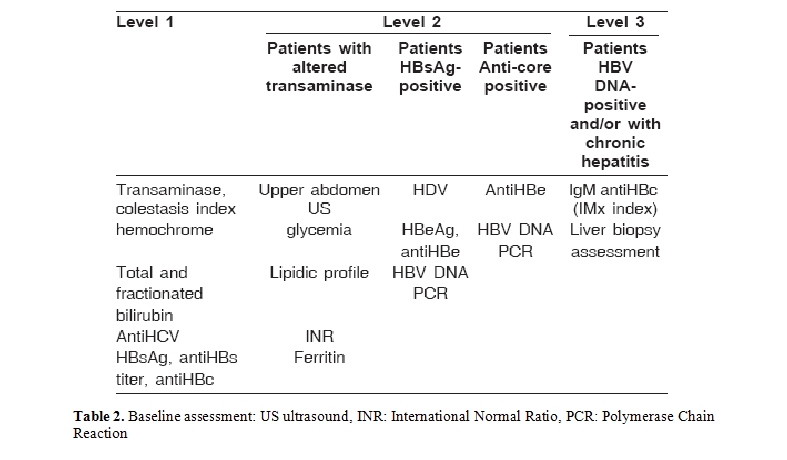

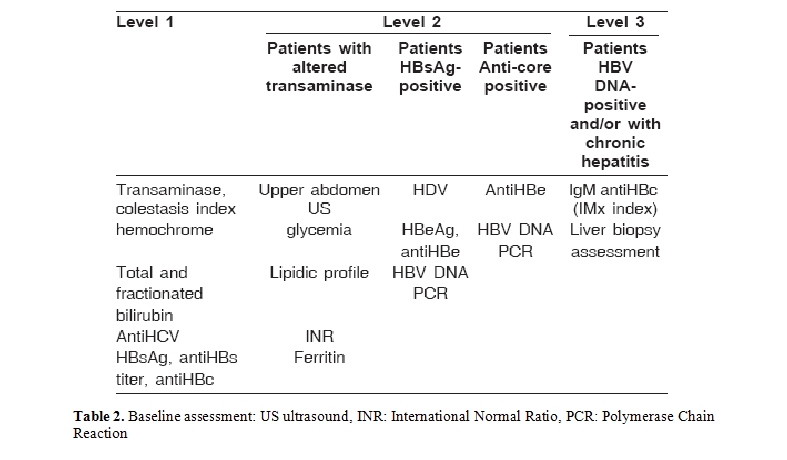

Clinical definitions: The assessment of chronic liver disease is the fundamental event of the diagnostic picture (baseline) (Table 2) and requires the use of all the instruments usually utilised in hepatology including, if necessary, trans-cutaneous or trans-jugular liver biopsy in subjects with coagulation problems (for example patients with blood or kidney diseases).

The baseline diagnosis of the disease is pivotal in the choice of which treatment to adopt, as the risk of severe complications is related to the severity of the underlying liver disease [5].

In order to standardize the deȚ nitions the following terms were suggested: 1) infection (not necessarily associated with reactivation of hepatitis) in the case of the detection of HBV DNA by sensitive HBV assays and/or of HBsAg in patients in whom these markers were originally negative, 2) reactivation of hepatitis B (hepatitis), in the presence of a significant viremia and ALT levels above the upper normal value.

Treatment Strategies

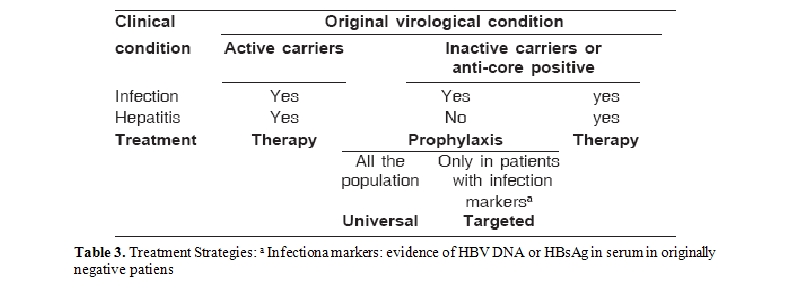

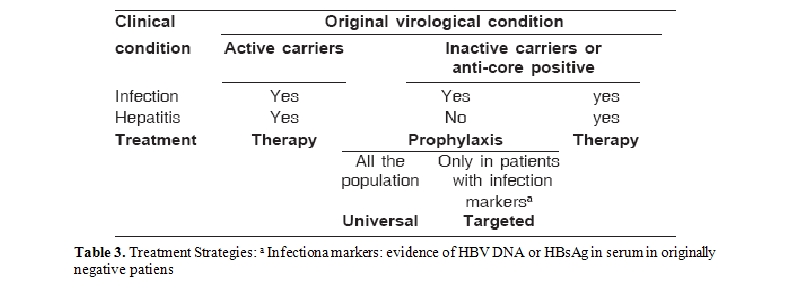

The term prophylaxis was used to mean treatment with antiviral drugs of an inactive or occult infection, with the aim of preventing hepatitis reactivation. Prophylaxis was defined as: 1) universal prophylaxis (UP), if it is carried out on the entire population potentially at risk (inactive carriers and/or anti-core), 2) or targeted prophylaxis (TP), if it is subordinate to the appearance of infection markers (HBV DNA and/or HBsAg) in the absence of hepatitis reactivation (Table 3). Therapy (T) was understood to mean the treatment of hepatitis B (i.e. chronic hepatitis in active carriers or hepatitis reactivation)

Treatment Options

In Italy the following drugs are available at present: interferons, either standard or peghilated (both little tolerated in the condition of immunodepression, especially in transplant patientsfor the potential risk of rejection) and the nucleos(t)ides analogs(NAs), which currently include lamivudine, adefovir-dipivoxil , entecavir, telbivudine and tenofovir and and emtricitabine for patients with HBV-HIV co-infection.

In naive patients lamivudine, which has a considerable antiviral effect, frequently (50-60% at 4 years, low genetic barrer) induces the selection of lamivudine-resistant mutants in locus YMDD of the polymerase gene (YMDD). However, adefovir-dipivoxil has a low antiviral effect but induce a lower selection of mutants, while Telbivudine is more potent with an intermediate genetic barrer. Finally, third generation NAs (Entecavir and Tenofovir) have both a high potency and a high genetic barrer[3].

Data from experience in liver transplanted and HIV patients have shown a relation between the original viremia, the degree of immunosuppression and the selection of mutants during prophylaxis with lamivudine.[9,10] Consequently a careful monitoring of the response to treatment and of the resistance is suggested in immunocompromised patients treated with Nas.

Hereafter are reported the statements of the Italian guidelines referred to hepatitis B and recently updated with a special attention to the different therapeutic options available nowadays.[8]

Screening. It is recommended that all immunocompromised patients and those candidate to chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy and/or transplantion are screened for HBsAg and anti-HBc. Seronegative patients should be vaccinated preferibly with a reinforced course of vaccination for the diminished vaccinal response linked to the immunocompromission.

Chronic carriers with active HBV replication (HBV DNA > 2.000 IU/mL). They should be treated as immune-competent patients. NAs are the first choice, regardless of the clinical setting (oncology, haematology, rheumatology, nephrology, gastroenterology, dermatology, solid organ transplantation). Pegylated interferon is contraindicated in most cases. NAs with high potency and low resistance should be used, such as Entecavir or Tenofovir. Telbivudine could be considered in those with HBV DNA < 2,000,000 IU/ml.

Close virologic monitoring is mandatory during immunosuppression. The addition of a second drug (a nucleotide in patients treated with a nucleoside and vice versa) is advisable in cases of incomplete virologic response, or primary non-response to monotherapy. In immunocompromised patients the dose of NA(s) should be adjusted according to the renal function, co-morbidities and drugs interactions.

Inactive HBsAg carriers (HBV DNA persistently < 2,000 IU/ml). In patients undergoing solid organs transplant or autologous or allogenic bone marrow transplantation or high risk immune suppressive treatment (anti-TNF, anti-CD20, anti-CD56, medium/high dose of steroids (>10 mg/die) for prolonged periods, ciclofosphamide, metotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine and micofenolate) antiviral prophylaxis with a NA is recommended, starting from the beginning of the immune-suppressive treatment or preferibly 2-4 weeks before. In other conditions patients should be only monitored for HBV DNA reactivation.

If the duration of immunosuppressive therapy is limited, the pharmacologic risk of resistence is diminished; therefore a low cost NA, such as Lamivudine, may be used. In patients who need prolonged immunosuppression the use of more potent NAs at lower risk to induce resistance can be considered).

HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc positive patients. In these subjects HBV DNA should be tested at baseline in order to distinguish real from false OBI. Viremic HBsAg-negative patients should be treated with a NA. Anti-HBc positive subjects with haematological diseases undergoing strongly immunosuppressive treatments such as: fludarabine, dose-dense regimens, autologous or allogenic bone marrow transplant, treatment with monoclonal antibodies (anti – CD-20 and anti CD52) should be treated with a NA (preferably Lamivudine for short term therapies),independently of anti- HBs reactivity.

Anti-HBc positive patients in other clinical settings should not be treated but only monitored for liver enzymes and the emergence of serum HBsAg every 1-3 months. Some experts recommend prophylaxis with a NA also in non-haematological patients if they are treated with anti-CD20.

Monitoring During Therapy

Once NAs therapy or prophylaxis has been started, monitoring will essentially be through testing serum HBV DNA and ALT levels every three months, to assess: 1) response to treatment (i.e. reduction of HBV DNA, preferably below the limit of sensitivity of the amplified techniques and ALT normalization) and 2) drug-resistance, which should be suspected in the case of virologic breakthrough while ontreatment, in order to activate an early rescue therapy[3,11]. Resistance can be defined clinically by the virologic breakthrough [4] but a genotypic testing is reccomended and should be used in order to better define the different mutations and to choose the rescue therapy [3,8].

Impact on Different Specialist Fields

Data regarding hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients are very heterogeneous. As a result there is a strong indication to promote studies aimed at defining the natural history of hepatitis B in these patients, to assess – also prospectively - different treatment protocols and to promote close cooperation among different specialists.

Oncology, Hematology and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Background: During chemotherapy hepatitis B can make its appearance in two different phases: 1) during the treatment, in relation to the intense bone marrow suppression, which is associated with a strong viral replication and, sometimes, with the emergence of a fulminant hepatitis in the form of fibrosing cholestasis, 2) after the end of therapy, as during the immuno-reconstitution phase the immune response can bring on a reactivation of hepatitis whose clinical course may be more or less severe depending on the baseline condition of the liver and other possible factors that may contribute to the damage.

In oncology the prevalence of HBsAg-positive patients ranges between 5.3% (in Europe) and 12% (in China). In these patients the frequency of clinical HBVreactivation ranges between 20 and 56%, correlating with the use of steroids, anthracyclines, 5-fluouracil with some virological indicators (presence of HBeAgor of e-minus variants and/or of a detectable HBV DNA prior to therapy). Theclinical significance of relapse has been clearly associated with the pre-chemotherapy liver function, with a mortality of 5-40%.

The reactivation of hepatitis, moreover, influences the continuation of the chemotherapy, inducing its suspension and not infrequently posing problems of differential diagnosis with regard to drug toxicity. Hepatitis B can develop both in active and in inactive carriers and it is generally associated with the reappearance of a significant viremia in the preceding 2-3 weeks.

In hematology the frequency of HBsAg positive patients is higher (12.2% in Greece and 8.8% in a recent study from Italy) and the risk of reactivation appears to be greater than in other settings of oncology, depending on the degree of immunosuppression. In this setting, control of the HBV infection assumes great importance in order to prevent HBV-related complications, but also so as not to modify a highly successful therapeutic schedule.In this field the main prognostic indicators unfavorably associated with hepatitis B reactivation are, besides those already cited, hyper-transaminasemia and the condition of second or third cycle compared to the first [1,12- 14].

In hematology, a 21-67% (median 50%) risk of reactivation has been described, with an average mortality of 20%. In this setting, the available literature is not clear whether the severity of hepatitis in HBsAg-positive patients is directly due to the liver damage caused by HBV reactivation or by other causes (i.e. VOD, GvHD or MOF) and also the degree of risk in relation to the condition of active or inactive carrier is not clearly determinable.

The risk would appear to be heightened by the use of monoclonal antibodies (antiCD20, antiCD52), with the possibility of hepatitis reactivation (even after a cycle of 1-3 months of prophylaxis with lamivudine) at a variable distance from the last administration of these drugs, particularly in overt carriers, but also in anti-core subjects. An analogous risk exists in the course of allogeneic HSCT, as the immuno-suppressive effect in the conditioning phase is particularly strong and is amplified by the subsequent anti-rejection therapy, so the risk of hepatitis reactivation remains throughout the phase of immuno-reconstitution (in some cases until 1-2 years from transplantation)[1,15-17,45].

Experiences in the different virological categories:

Recommendations from the Italian guidelines:

Effects of different virological conditions in donors (D) and recipients (R) of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT):

General recommendations in HSCT:

Background: Dialysis: The incidence of overtcarriers of HBsAg among dialyzed patients is 0-7% in developed countries and 10-20% in developing ones. In these subjects the frequent normality of the transaminase makes clinical judgment difficult, confirming the fundamental role of the virological markers (quantitative HBV DNA) and of the liver biopsy to distinguish between active and inactive carriers (baseline). In this setting data about the condition of OBI carrier among anti-HBc patients are scarce and consider the sole presence of viremia in serum, whose diagnostic sensitivity is low.

In kidney transplant the condition of HBsAg carrier can be estimated in 10-20% of cases and is associated with a significantly higher risk of death (OR 2.49, 95% CI), independent of the viremic condition (active or inactive carrier), and the chronic hepatitis presents an accelerated course towards cirrhosis (5.3-12%-year), decompensation and hepatocarcinoma [23,24].

In heart and lung transplant, Italian reports have signalled HBsAg positivity in 2.3-3.7% of recipients. In this setting the evolution of the HBV-related disease is accelerated in active carriers and the risk of hepatitis B reactivation post-transplant is over 50% in originally inactive subjects. Finally, the risk of sero-reversion postsurgery (de-novo hepatitis B) in HbsAg-negative/anti-HBc positive recipients seems to be lower than 5% [25-27].

Clinical experiences in nephrology: No controlled trials for the treatment of HBV with either interferon or lamivudine in dialyzed patients or in kidney transplants are currently available. Interferon can be used to treat dialyzed patients with chronic hepatitis B, but it is contraindicated in transplanted patients. Short-term administration of lamivudine monotherapy is effective but when the drug is withdrawn, viremia rebounds and hepatitis relapses in most cases. Continuous administration of lamivudine monotherapy for 3 to 4 years is able to obtain long-term suppression of HBV replication and may prevent the development of liver related complications and mortality [28]. Secondary treatment failure is caused by the emergence of YMDD which, in some patients, herald hepatitic flares and progression of the liver disease.

Recommendations in relation to transplant recipients from the Italian guidelines:

Recommendations in relation to transplant donors:

Background: The risk of post transplantation hepatitis B is strictly influenced from both recipient and donor virological characteristics:

Rheumatology

Background: Reports regarding the reactivation of HBV in the rheumatology setting are episodic, during the course of hydroxychlorochine, azathioprine, methotrexate and anti-Tumor Necrosis factor (TNF). The few data available all refer to active and inactive HBsAg carriers. However, reports on anti-CD20 derive from hematological experience, and like in hematology the risk of HBV reactivation in the rheumatology setting would appear to be linked both to the phase of immuno-suppression and to that of immuno-reconstitution.

In the meantime no reactivations have been reported in the few HbsAg-positive rheumatology patients undergoing universal prophylaxis with lamivudine during immunosuppressive therapy.[38-41]

In the absence of data two risk categories have been identifiedwith regard to the type and to the degree of immunosuppression: a) high risk of HBV reactivationin patients undergoing the following therapy: anti-TNF antibodies, medium to high dosage steroids (>7.5 mg/die) for prolonged periods, immunosuppressors such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine and mycophenolate. Although cases of viral reactivation have not yet been described in rheumatology patients undergoing treatment with anti-CD20 antibodies, the data which have emerged in other specialist circles suggest the inclusion in this group of these and other monoclonals; b) low risk of HBV reactivation in patients treated with steroids at <7.5 mg/die, sulfasalazine and hydroxychlorochine1.

Recommendations from the Italian guidelines: Among HBsAg-positive patients, therapy is indicated in active carriers and universal prophylaxis with a NA is suggested in inactive carriers who underwent high-risk treatment, especially if they are subjects with manifestations of chronic liver disease due to the previous activity of HBV or other causes. Finally, in inactive HBsAg-carriers treated with low risk therapies and in HbsAg-negative/ anti-HBc positive subjects the proposal is a strategy of monitoring,with the activation of therapy or targeted prophylaxis in the case of viral reactivation (HBV DNA > 20,000 IU/ml) or sero-reversion, respectively.

Prophylaxis should be started 2-4 weeks before the immunosuppressive therapy, if possible, and continued for at least 6-12 months afterwards (i.e. after immunosuppressive therapy has been suspended). Hematology literature advises particular caution in suspending prophylaxis, especially in subjects treated with repeated cycles of monoclonal antibodies.

Peculiar conditions in the rheumatology setting: Anti-HBV vaccination in rheumatology patients remains controversial and its cost/benefit ratio should be carefully assessed in groups particularly at risk of HBV (for example those living with HBsAg-positive individuals or health workers).

Panarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare necrotizing vasculitis that affects small and medium-sized arteries which presents, at least in a portion of cases, a pathogenic correlation with HBV infection. In the treatment of HBV-related PAN, the immunosuppressive therapy (which also poses the question of an uncontrolled activation of the virus) should be associated with an antiviral therapy (in active carriers) or universal prophylaxis (in inactive carriers) to repress viral replication. In this regard single cases and observational studies with small numbers of cases have documented the efficacy of interferon (IFN) and lamivudine.

HIV

Background: Cirrhosis and liver cancer are the second cause of death worldwide in HIV carriers (3-4 million), 9% of whom have HBV infection. Co-infection with HIV increases the rate of chronic HBV infection, reduces the annual rate of seroconversion to antiHBe and to antiHBs and may be linked to the reactivation of the occult infection in HBsAg-negative subjects in the presence of severe immunodepletion.

Moreover co-infection with HIV accelerates progression towards cirrhosis and liver decompensation and reduces survival in decompensated cirrhotics. Therefore mortality due to liver disease in those co-infected with HIV-HBV is higher compared to subjects with just HBV infection [43-44].

Recommendations from the Italian guidelines:

Immunodepression due to the underlying disease or to drugs used in immunosuppressive, anticancer therapy and in organ transplants can influence the hepatitis B virus (HBV), both in terms of reactivation and in terms of the acceleration of a pre-existing chronic hepatitis. In this situation the possibility of HBV relapse has been known for years, with clinical manifestations ranging from selflimiting anicteric to fulminant forms or to chronic hepatitis with an accelerated clinical course towards liver decompensation. Hepatitis reacti-vation may influence the continuation of the specific treatments and the survival of immuno-depressed or transplanted patients[1].

The risk of clinical events is mainly observed in overt carriers of HBV, but can also develop in the OBI condition which has been widely described in the literature of the last decade.[2]

Progress in the diagnostic procedures of the various virological conditions associated with HBV, the recent availability of effective antiviral treatments, the growing incidence of immunocompromised patients attributable to the evolution of immunosuppressive therapies and organ transplants and the expectation of an important future increase of HBV reactivation have brought this problem to the fore, although the rational approach and management of these patients is still debated.

Definitions

Virological characteristics: Persistent HBV infection is defined as overt when the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is present in amounts well-detectable by sensitive immune assays and occult in HBsAg-negative subjects with evidence of intrahepatic and/or serum HBV DNA.[2] In occult carriers, HBsAg can be completely absent (real OBI) or undetectable for very low amounts or polymorphisms (false OBI).

- A. HBV carriers (HBsAg-positive). In accordance with the international definitions, they can be identified as: 1) active carriers, in presence of HBeAg or of anti-HBe antibodies and of a viral load ≥ 2-20,000 IU/ml; this condition is associated with the presence of hepatic disease in the most part of cases, or 2) inactive carriers,in case of subjects HBeAg-negative and antiHBe-positive, whose alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are persistently within the normal range, HBV DNA below 2,000 IU/ml in the most part of cases and IgM antiHBc levels < 0.20 IMx Index. In the majority of these subjects the histological finnding, when available, does not reveal a significant liver disease (necro-inflammatory activity < 4 HAI), while in a small minority of cases it is possible to observe the effects of a chronic liver disease which became silent spontaneously or following antiviral treatment [3,4].

- B. Occult HBV carriers (HBsAg-negative).The difficulty in determining HBV DNA in the liver biopsy (frequently not justified in subjects without clinical signs of hepatitis), the rare presence of detectable viremia in serum even with sensitive techniques, and the frequent presence in occult carriers of markers of previous contact with the HBV (antiHBc+/- antiHBs), leads one to consider all anti-HBc (anti-core)-positivesubjectsas potential occult carriers. Instead there are no serum determinants in the minority (about 20%) of occult carriers who are negative for all HBV markers.

Virological events: In HBV carriers (occult or overt) the following virological events are considered significant: 1) in anti-core subjects the reemergence of HBsAg(sero-reversion), 2) in inactive carriers the appearance of a significant viremia (≥20,000 IU/ml) (reactivation), as this is frequently associated with liver damage due to HBV, 3) in active carriers the persistence of a significant viremia (> 20,000 IU/ml in HBeAg positive patients and > 2,000 IU/ml in HBeAg negative subjects) (activity), as this is frequently associated with progression of liver damage due to HBV, 4) in all the virological categories (whether or not during prophylaxis or therapy with antivirals), the increase in at least one logarithm of HBV DNA, compared to its nadir, reconfermed in two consecutive serum tests during monitoring (virologic breakthrough) (Table 1)[4].

Clinical definitions: The assessment of chronic liver disease is the fundamental event of the diagnostic picture (baseline) (Table 2) and requires the use of all the instruments usually utilised in hepatology including, if necessary, trans-cutaneous or trans-jugular liver biopsy in subjects with coagulation problems (for example patients with blood or kidney diseases).

The baseline diagnosis of the disease is pivotal in the choice of which treatment to adopt, as the risk of severe complications is related to the severity of the underlying liver disease [5].

In order to standardize the deȚ nitions the following terms were suggested: 1) infection (not necessarily associated with reactivation of hepatitis) in the case of the detection of HBV DNA by sensitive HBV assays and/or of HBsAg in patients in whom these markers were originally negative, 2) reactivation of hepatitis B (hepatitis), in the presence of a significant viremia and ALT levels above the upper normal value.

Treatment Strategies

The term prophylaxis was used to mean treatment with antiviral drugs of an inactive or occult infection, with the aim of preventing hepatitis reactivation. Prophylaxis was defined as: 1) universal prophylaxis (UP), if it is carried out on the entire population potentially at risk (inactive carriers and/or anti-core), 2) or targeted prophylaxis (TP), if it is subordinate to the appearance of infection markers (HBV DNA and/or HBsAg) in the absence of hepatitis reactivation (Table 3). Therapy (T) was understood to mean the treatment of hepatitis B (i.e. chronic hepatitis in active carriers or hepatitis reactivation)

Treatment Options

In Italy the following drugs are available at present: interferons, either standard or peghilated (both little tolerated in the condition of immunodepression, especially in transplant patientsfor the potential risk of rejection) and the nucleos(t)ides analogs(NAs), which currently include lamivudine, adefovir-dipivoxil , entecavir, telbivudine and tenofovir and and emtricitabine for patients with HBV-HIV co-infection.

In naive patients lamivudine, which has a considerable antiviral effect, frequently (50-60% at 4 years, low genetic barrer) induces the selection of lamivudine-resistant mutants in locus YMDD of the polymerase gene (YMDD). However, adefovir-dipivoxil has a low antiviral effect but induce a lower selection of mutants, while Telbivudine is more potent with an intermediate genetic barrer. Finally, third generation NAs (Entecavir and Tenofovir) have both a high potency and a high genetic barrer[3].

Data from experience in liver transplanted and HIV patients have shown a relation between the original viremia, the degree of immunosuppression and the selection of mutants during prophylaxis with lamivudine.[9,10] Consequently a careful monitoring of the response to treatment and of the resistance is suggested in immunocompromised patients treated with Nas.

Hereafter are reported the statements of the Italian guidelines referred to hepatitis B and recently updated with a special attention to the different therapeutic options available nowadays.[8]

Screening. It is recommended that all immunocompromised patients and those candidate to chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy and/or transplantion are screened for HBsAg and anti-HBc. Seronegative patients should be vaccinated preferibly with a reinforced course of vaccination for the diminished vaccinal response linked to the immunocompromission.

Chronic carriers with active HBV replication (HBV DNA > 2.000 IU/mL). They should be treated as immune-competent patients. NAs are the first choice, regardless of the clinical setting (oncology, haematology, rheumatology, nephrology, gastroenterology, dermatology, solid organ transplantation). Pegylated interferon is contraindicated in most cases. NAs with high potency and low resistance should be used, such as Entecavir or Tenofovir. Telbivudine could be considered in those with HBV DNA < 2,000,000 IU/ml.

Close virologic monitoring is mandatory during immunosuppression. The addition of a second drug (a nucleotide in patients treated with a nucleoside and vice versa) is advisable in cases of incomplete virologic response, or primary non-response to monotherapy. In immunocompromised patients the dose of NA(s) should be adjusted according to the renal function, co-morbidities and drugs interactions.

Inactive HBsAg carriers (HBV DNA persistently < 2,000 IU/ml). In patients undergoing solid organs transplant or autologous or allogenic bone marrow transplantation or high risk immune suppressive treatment (anti-TNF, anti-CD20, anti-CD56, medium/high dose of steroids (>10 mg/die) for prolonged periods, ciclofosphamide, metotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine and micofenolate) antiviral prophylaxis with a NA is recommended, starting from the beginning of the immune-suppressive treatment or preferibly 2-4 weeks before. In other conditions patients should be only monitored for HBV DNA reactivation.

If the duration of immunosuppressive therapy is limited, the pharmacologic risk of resistence is diminished; therefore a low cost NA, such as Lamivudine, may be used. In patients who need prolonged immunosuppression the use of more potent NAs at lower risk to induce resistance can be considered).

HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc positive patients. In these subjects HBV DNA should be tested at baseline in order to distinguish real from false OBI. Viremic HBsAg-negative patients should be treated with a NA. Anti-HBc positive subjects with haematological diseases undergoing strongly immunosuppressive treatments such as: fludarabine, dose-dense regimens, autologous or allogenic bone marrow transplant, treatment with monoclonal antibodies (anti – CD-20 and anti CD52) should be treated with a NA (preferably Lamivudine for short term therapies),independently of anti- HBs reactivity.

Anti-HBc positive patients in other clinical settings should not be treated but only monitored for liver enzymes and the emergence of serum HBsAg every 1-3 months. Some experts recommend prophylaxis with a NA also in non-haematological patients if they are treated with anti-CD20.

Monitoring During Therapy

Once NAs therapy or prophylaxis has been started, monitoring will essentially be through testing serum HBV DNA and ALT levels every three months, to assess: 1) response to treatment (i.e. reduction of HBV DNA, preferably below the limit of sensitivity of the amplified techniques and ALT normalization) and 2) drug-resistance, which should be suspected in the case of virologic breakthrough while ontreatment, in order to activate an early rescue therapy[3,11]. Resistance can be defined clinically by the virologic breakthrough [4] but a genotypic testing is reccomended and should be used in order to better define the different mutations and to choose the rescue therapy [3,8].

Impact on Different Specialist Fields

Data regarding hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients are very heterogeneous. As a result there is a strong indication to promote studies aimed at defining the natural history of hepatitis B in these patients, to assess – also prospectively - different treatment protocols and to promote close cooperation among different specialists.

Oncology, Hematology and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Background: During chemotherapy hepatitis B can make its appearance in two different phases: 1) during the treatment, in relation to the intense bone marrow suppression, which is associated with a strong viral replication and, sometimes, with the emergence of a fulminant hepatitis in the form of fibrosing cholestasis, 2) after the end of therapy, as during the immuno-reconstitution phase the immune response can bring on a reactivation of hepatitis whose clinical course may be more or less severe depending on the baseline condition of the liver and other possible factors that may contribute to the damage.

In oncology the prevalence of HBsAg-positive patients ranges between 5.3% (in Europe) and 12% (in China). In these patients the frequency of clinical HBVreactivation ranges between 20 and 56%, correlating with the use of steroids, anthracyclines, 5-fluouracil with some virological indicators (presence of HBeAgor of e-minus variants and/or of a detectable HBV DNA prior to therapy). Theclinical significance of relapse has been clearly associated with the pre-chemotherapy liver function, with a mortality of 5-40%.

The reactivation of hepatitis, moreover, influences the continuation of the chemotherapy, inducing its suspension and not infrequently posing problems of differential diagnosis with regard to drug toxicity. Hepatitis B can develop both in active and in inactive carriers and it is generally associated with the reappearance of a significant viremia in the preceding 2-3 weeks.

In hematology the frequency of HBsAg positive patients is higher (12.2% in Greece and 8.8% in a recent study from Italy) and the risk of reactivation appears to be greater than in other settings of oncology, depending on the degree of immunosuppression. In this setting, control of the HBV infection assumes great importance in order to prevent HBV-related complications, but also so as not to modify a highly successful therapeutic schedule.In this field the main prognostic indicators unfavorably associated with hepatitis B reactivation are, besides those already cited, hyper-transaminasemia and the condition of second or third cycle compared to the first [1,12- 14].

In hematology, a 21-67% (median 50%) risk of reactivation has been described, with an average mortality of 20%. In this setting, the available literature is not clear whether the severity of hepatitis in HBsAg-positive patients is directly due to the liver damage caused by HBV reactivation or by other causes (i.e. VOD, GvHD or MOF) and also the degree of risk in relation to the condition of active or inactive carrier is not clearly determinable.

The risk would appear to be heightened by the use of monoclonal antibodies (antiCD20, antiCD52), with the possibility of hepatitis reactivation (even after a cycle of 1-3 months of prophylaxis with lamivudine) at a variable distance from the last administration of these drugs, particularly in overt carriers, but also in anti-core subjects. An analogous risk exists in the course of allogeneic HSCT, as the immuno-suppressive effect in the conditioning phase is particularly strong and is amplified by the subsequent anti-rejection therapy, so the risk of hepatitis reactivation remains throughout the phase of immuno-reconstitution (in some cases until 1-2 years from transplantation)[1,15-17,45].

Experiences in the different virological categories:

- Active HBsAg-carriers: In the onco-hematological setting lamivudine therapy of chronic hepatitis in active carriers appears to be effective.[1]

- Inactive HBsAg-carriers: The start of lamivudine therapy at the time of the clinical relapse (hepatitis) in inactive carriersmaintains a residual mortality of 20%, probably in relation to the baseline conditions and to the delayed treatment.However, in retrospective studies lamivudine has been shown to be effective in prophylaxis of hepatitis B (0-9% of hepatitis reactivation compared to 25-85% in untreated patients) and in the only prospective study hepatitis relapse developed in 5% of treated subjects and in 24% of controls. Moreover, in the study the universal use of lamivudine was better than the targeted prophylaxis (activated only at the appearance of HBV DNA with a non-amplified technique, during bimonthly monitoring), both in terms of survival and of hepatitis reactivation (0% vs.53%, P=0.002)[1,17,18,49,50].Recently many meta-analyses have confirmed the signficant efficacy of lamivudine in preventing hepatitis B in HBsAg positive patients, in reducing deaths and in reducing chemotherapy discontinuation.Finally, as lately reported in literature, lamivudine-prophylaxis in HBsAg-positive patients undergoing chemotherapy has been shown to be cost-effectivein terms of HBV reactivation (9.6% LAM+ vs. 43.8% LAM-), liver related deaths (0/500 LAM+ vs 20/500 LAM-), chemotherapy discontinuation and cancer deaths (39/500 LAM+ vs 47/500 LAM-)[46-48].

- Anti-core patients (HBsAg-negative): In the oncological

setting there are few data, at present, for this virological category,

which can reach 20-40% in averagely endemic areas and 70-80% in highly

endemic areas.However, in the hematological setting, out of a total of

176 patients described in literature, sero-reversion has been reported

in 21 subjects (12%) during conventional chemotherapy, whether or not

this was associated with HSCT, with percentages of 4-30% during

chemotherapy and 14-50% in the course of autologous

transplantation.After

autologous HSCT, hepatitis B developed in anti-HBc patients later (6-52

months, average 19 months) than in overt carriers (average 2-3 months)

and none of the patients described died of hepatitis B (in 7 cases

during therapy with lamivudine, started at the time of the clinical

relapse). After the reactivation nine of the 10 patients remained HBsAg

positive and one lost the HBsAg during follow-up. Instead, two deaths

out of 39 subjects with seroreversion have been reported in literature

after allogeneic HSCTand this appeared to have been significantly

linked to the absence of protective antibodies (antiHBs) in the donor

and to GVHD1.Recently the introduction in hematologic treatments of

monoclonal anti-lymphocyte B and T antibodies (anti-CD20 and

anti-CD52), used alone or together with chemotherapy, has been

associatedwith the signaling of some cases of sero-reversion in

anti-core subjects, sometimes with a fulminant form and death of the

patients, despite therapy with lamivudine1.HBV infection has been

described to be the most frequently (39%) experienced viral infection

in lymphoma patients treated with Rituximab. In a study about 50% of

Rituximab-related HBV infections resulted in death, whereas this was

the case in only 33% of the patients with other infections.An Italian

study has lately stressed a very low (1%) overall risk of

sero-reversion in a large series of patients treated for lymphoma, but

the risk of hepatitis B reactivation was 3.5 fold increased. Rituximab

therapy, compared to conventional chemotherapy (P < 0.005). Data

confirming the increased risk of HBV reactivation in patients

undergoing anti B-cell therapy have also emerged in a trial which

showed as alemtuzumab containing chemotherapy regimen was associated

with a high risk (29%) of reactivation of occult HBV infection and of

severe HBV-related hepatitis [51-54].

Recommendations from the Italian guidelines:

- In active carriers therapy is considered useful to control the liver disease pre- and post-immunosuppressive treatments. In HSCT, in particular, the control of the HBV-related disease permits a more precise diagnosis and treatment of specific liver complications (GVHD and VOD). In these patients, antiviral therapy should be continued lifelong (due to the high risk of relapse after withdrawal) or at least until the disappearance of HBsAg in serum. A strict monitoring of mutants should be activated, in order to prevent hepatitis relapse with rescue therapy.

- In the inactive carriers universal prophylaxis appears to be indicated and should be continued for the entire phase of chemotherapy, until at least 12-18months after the end of the treatment.[1,18] The optimal duration of the prophylaxis is still debated and requires prospective studies. In any case, it is recommended the monitoring of the viremia after suspension, for the prompt diagnosis and return to treatment in the case of reactivation.

- In anti-HBc positive (HBsAg-negative) patients, two different strategies can be identified:

- a) in oncology or in patients undergoing mild hematological therapies (judged to be at low immunosuppressive potential, such as the ABVD of the CHOP 21 days scheme), HBsAg monitoring every 1-3 months is advised, with the activation of targeted prophylaxis or therapy in the case of sero-reversion or hepatitis reactivation, respectively. However,the use of HBV DNA monitoring for targeted prophylaxis remains controversial because of the lack of data referred to the timing and duration of the monitoring and to the clinical significance of minimal levels of detectable viremia (i.e. the presence of low levels of serum HBV DNA in OBI carriers after solid organs transplantation has rarely a clinical impacts and is not constantly associated with hepatitis relapse)[19].

- b) In subjects who need to be treated with intense immunosuppression(chemotherapy with fludarabine, dose-sense regimes, allogeneic transplant, autologous myeloablative transplant, induction in acute leukemia, use of monoclonal antibodies) universal prophylaxis is proposed.

Effects of different virological conditions in donors (D) and recipients (R) of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT):

- D (HBsAg-/antiHBs+/antiHBc±)->R (HBsAg+):In the case of transplant from an immunized (antiHBs-positive) donor to an overt carrier (HBsAg-positive) recipient two possible scenarios have been described: a) the chance of adoptive transfer of immunity with the possible clearance of HBsAg (especially if recipients are treated with lamivudine), b) an acute and sometimes fulminant hepatitis (in historical series)[1].

- D (HBsAg-/antiHBs±/anti-HBc+)->R (HbsAg-/antiHBs±/anti-HBc ±): Only few data are available, indicating that in the case of transplant from an anti-HBc positive donor the risk of sero-reversion in the recipient would appear to be negligible in both anti-HBc positive and negative recipients [21].

- D (HBsAg+).>R (HBsAg-): In a few studies, transplant from an HBsAg-positive donor was associated with hepatitis in 44-62% of recipients, with generic hepatic mortality in 33-75% of cases, although the role of HBV in these clinical events was not well defined. In a historical retrospective multicenter study performed in the pre-antiviral phase, the anti-HBV specific immunoglobulins (HBIG) were not protective against the transmission of the infection. In contrast, in a recent study the activation of therapy with lamivudine in donors and of prophylaxis with the same antiviral in recipients significantly reduced the HBV-related hepatitis rate (48 vs. 7%, P=0.002) and mortality (24 vs. 0%, P=0.01) compared to a historical control group[1]. Furthermore two case reports have confirmed the efficacy of lamivudine-prophylaxis in this clinical setting in preventing HBV related hepatitis[55,56].

General recommendations in HSCT:

- Vaccination of the recipient prior to transplant, if possible, with accelerated protocols, (recombinant vaccine 40 ”g by intramuscular route, time 0-1-2 months or 0-7-21 days), especially if he/she is naïve.

- Vaccination of the donor not immunized prior to transplant, with accelerated protocols (recombinant vaccine 20 ”g by intramuscular route time 0-1-2 months or 0-7-21 days) in the case of allogeneic HSCT.

- Treatment of the HBsAg-positive donor with lamivudine pre- HSCT in order to reduce infectivity through the reduction of viremia (preferably below the limit of sensitivity of an amplified assay) and universal prophylaxis of the recipient on the day before the transplant.

- The use of high doses of HBIG (intravenous 10,000 IU)

during infusion of hematopoietic stem cells from overt carriers (who

have been preventively treated with antivirals) in HBsAg-negative

recipients remains controversial. Because of the actual results of the

hepatologic and hematologic therapy there is no reason to deny

hematopoietic stem transplantation from an HBV positive donor (any

form) if the risk-benefit ratio is in favor of transplantation.

Moreover in the case of an HLA identical family HBV positive member

there is no point in wasting time and resources in searching for an

unrelated donor in the international bone marrow donor bank.

Background: Dialysis: The incidence of overtcarriers of HBsAg among dialyzed patients is 0-7% in developed countries and 10-20% in developing ones. In these subjects the frequent normality of the transaminase makes clinical judgment difficult, confirming the fundamental role of the virological markers (quantitative HBV DNA) and of the liver biopsy to distinguish between active and inactive carriers (baseline). In this setting data about the condition of OBI carrier among anti-HBc patients are scarce and consider the sole presence of viremia in serum, whose diagnostic sensitivity is low.

In kidney transplant the condition of HBsAg carrier can be estimated in 10-20% of cases and is associated with a significantly higher risk of death (OR 2.49, 95% CI), independent of the viremic condition (active or inactive carrier), and the chronic hepatitis presents an accelerated course towards cirrhosis (5.3-12%-year), decompensation and hepatocarcinoma [23,24].

In heart and lung transplant, Italian reports have signalled HBsAg positivity in 2.3-3.7% of recipients. In this setting the evolution of the HBV-related disease is accelerated in active carriers and the risk of hepatitis B reactivation post-transplant is over 50% in originally inactive subjects. Finally, the risk of sero-reversion postsurgery (de-novo hepatitis B) in HbsAg-negative/anti-HBc positive recipients seems to be lower than 5% [25-27].

Clinical experiences in nephrology: No controlled trials for the treatment of HBV with either interferon or lamivudine in dialyzed patients or in kidney transplants are currently available. Interferon can be used to treat dialyzed patients with chronic hepatitis B, but it is contraindicated in transplanted patients. Short-term administration of lamivudine monotherapy is effective but when the drug is withdrawn, viremia rebounds and hepatitis relapses in most cases. Continuous administration of lamivudine monotherapy for 3 to 4 years is able to obtain long-term suppression of HBV replication and may prevent the development of liver related complications and mortality [28]. Secondary treatment failure is caused by the emergence of YMDD which, in some patients, herald hepatitic flares and progression of the liver disease.

Recommendations in relation to transplant recipients from the Italian guidelines:

- Active carrier: In candidates for kidney, heart or lung transplant the indication to therapy is confirmed, both in the pre-transplant (with NAs or interferons, when they are tolerated) and in the post-transplant phase (only NAs in view of the high risk of interferon-induced rejection).

- Inactive carrier: Pre-transplant and during dialysis there is no indication for prophylaxis but biochemical and virological monitoring is advised, if the diagnosis has been confirmed by strict adherence to previously defined criteria. Instead, therapy should be used in the re-activated forms (HBV DNA >20,000 IU/ml), especially if associated with significant liver damage (HAI > 4 and/or signs of Ț brotic disease by non-invasive methods). Post-transplant, however, there is an indication to universal prophylaxis,in relation to the available data on mortality in HBV carriers, independently from their virological condition.[23]

- Anti-HBc positive recipient: In these recipients of kidney, heart and lung transplant the presence of subclinical manifestations (low levels of circulating HBV DNA detectable with very sensitive techniques post-transplant) without sero-reversion in over 95% of cases[19,23,24,27] has been indicated.

Recommendations in relation to transplant donors:

- Anti-HBc positive donors: In the case of kidney, heart or lung allocation from an HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc ositive/antiHBs-positive or negative donor in a HBsAg-negative recipient, the risk of hepatitis B appears to be less than 5% [27,29]. The low risk does not justify preventive prophylaxis, but only HBsAg monitoring (every 3-6 monthsand/or in the case of transaminase increase) and the use of targeted prophylaxis or therapy only in the case of sero-reversion.

- HBsAg-positive donors: In this condition the risk of transmission of the HBV infection is very high in the absence of prophylaxis, especially from HBeAg-positive donors.[30] Recently some reports have indicated the post-transplant control of hepatitis B in HBsAg-negative/antiHBs-positive recipients of organs from HBsAg-positive donors, while on lamivudine prophylaxis [31].

Background: The risk of post transplantation hepatitis B is strictly influenced from both recipient and donor virological characteristics:

- HBsAg-positive recipients: in the absence of pre- and postoperative prophylaxis the risk of post-transplantation hepatitis B is over 80%.In this condition the use of antivirals before transplant (one single antiviral in the case of wild type virus, combined with a second one that is active on the mutants, in the condition of drug resistance with active replication), associated with HBIG after surgery (combined prophylaxis), is protective in more than 90% of patients [32,33].

- HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc positive recipients: in absence of prophylaxis the risk of sero-reversion after transplantation (de-novo hepatitis B) is less than 5% from naïve liver donors and 10-15% from anti-HBc positive donors[19,34].

- HBsAg-positive donors: the risk of hepatitis B transmission from a HBsAg-positive donor is high, as the neutralizing effect of HBIG is very low and the reappearance of HDV, in co-infected recipients, is constant. In this particular condition the reactivation of hepatitis would appear to be controlled by the combination of two antivirals in the long term [35].

- HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc positive donors: in this category the overall risk of HBV transmission and hepatitis is high (33-78%), in the absence of prophylaxis, ranging from 70% in naïve to 10-15% in anti-core recipients. Combined prophylaxis with lamivudine±HBIG controls relapse in nearly all cases, while personalized prophylaxis with only HBIG or only lamivudine has been suggested in low risk recipients (anti-core positive)[34]. Comparative studies are not available in this setting.

- in active carriers, therapybefore surgery is indicated (with one or two antivirals in cases of YMDD mutants), with the aim of achieving the reduction of HBV DNA below the limit of sensitive HBV assays or at least below < 20,000 IU/ml, in association with combined prophylaxis (HBIG and one or two antivirals, as previously reported) in the post-operative period;

- in inactive carriers, the role of therapy before surgery remains controversial because of the high (> 80%) protective effect of post-transplantation combined prophylaxis. In these subjects a preventive reduction of HBV DNA before surgery might not be necessary, with regard to the minimal residual risk, but it could be desirable in order to save HBIG in the long term after liver transplantation. Likewise, insubjects with spontaneous undetectable viremia (PCR-negative) or with levels around the limit of detectability (< 2,000 IU/ml), especially if co-infected with HDV, the protective power of just HBIG seems to be very high. Although also in this conditionthe use of the combined prophylaxis after liver transplantation permits a considerable saving of HBIG in the long term.

- in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc positive recipients, in analogy with what has been described in the other transplants, albeit in the presence of serum and intra-hepatic evidence of re-infection by HBV in the post-transplant period, the risk of sero-reversion is practically nil [36-37] and so there is no indication for any prophylaxis, but only the monitoring of the HBsAg.

Rheumatology

Background: Reports regarding the reactivation of HBV in the rheumatology setting are episodic, during the course of hydroxychlorochine, azathioprine, methotrexate and anti-Tumor Necrosis factor (TNF). The few data available all refer to active and inactive HBsAg carriers. However, reports on anti-CD20 derive from hematological experience, and like in hematology the risk of HBV reactivation in the rheumatology setting would appear to be linked both to the phase of immuno-suppression and to that of immuno-reconstitution.

In the meantime no reactivations have been reported in the few HbsAg-positive rheumatology patients undergoing universal prophylaxis with lamivudine during immunosuppressive therapy.[38-41]

In the absence of data two risk categories have been identifiedwith regard to the type and to the degree of immunosuppression: a) high risk of HBV reactivationin patients undergoing the following therapy: anti-TNF antibodies, medium to high dosage steroids (>7.5 mg/die) for prolonged periods, immunosuppressors such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, azathioprine and mycophenolate. Although cases of viral reactivation have not yet been described in rheumatology patients undergoing treatment with anti-CD20 antibodies, the data which have emerged in other specialist circles suggest the inclusion in this group of these and other monoclonals; b) low risk of HBV reactivation in patients treated with steroids at <7.5 mg/die, sulfasalazine and hydroxychlorochine1.

Recommendations from the Italian guidelines: Among HBsAg-positive patients, therapy is indicated in active carriers and universal prophylaxis with a NA is suggested in inactive carriers who underwent high-risk treatment, especially if they are subjects with manifestations of chronic liver disease due to the previous activity of HBV or other causes. Finally, in inactive HBsAg-carriers treated with low risk therapies and in HbsAg-negative/ anti-HBc positive subjects the proposal is a strategy of monitoring,with the activation of therapy or targeted prophylaxis in the case of viral reactivation (HBV DNA > 20,000 IU/ml) or sero-reversion, respectively.

Prophylaxis should be started 2-4 weeks before the immunosuppressive therapy, if possible, and continued for at least 6-12 months afterwards (i.e. after immunosuppressive therapy has been suspended). Hematology literature advises particular caution in suspending prophylaxis, especially in subjects treated with repeated cycles of monoclonal antibodies.

Peculiar conditions in the rheumatology setting: Anti-HBV vaccination in rheumatology patients remains controversial and its cost/benefit ratio should be carefully assessed in groups particularly at risk of HBV (for example those living with HBsAg-positive individuals or health workers).

Panarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare necrotizing vasculitis that affects small and medium-sized arteries which presents, at least in a portion of cases, a pathogenic correlation with HBV infection. In the treatment of HBV-related PAN, the immunosuppressive therapy (which also poses the question of an uncontrolled activation of the virus) should be associated with an antiviral therapy (in active carriers) or universal prophylaxis (in inactive carriers) to repress viral replication. In this regard single cases and observational studies with small numbers of cases have documented the efficacy of interferon (IFN) and lamivudine.

HIV

Background: Cirrhosis and liver cancer are the second cause of death worldwide in HIV carriers (3-4 million), 9% of whom have HBV infection. Co-infection with HIV increases the rate of chronic HBV infection, reduces the annual rate of seroconversion to antiHBe and to antiHBs and may be linked to the reactivation of the occult infection in HBsAg-negative subjects in the presence of severe immunodepletion.

Moreover co-infection with HIV accelerates progression towards cirrhosis and liver decompensation and reduces survival in decompensated cirrhotics. Therefore mortality due to liver disease in those co-infected with HIV-HBV is higher compared to subjects with just HBV infection [43-44].

Recommendations from the Italian guidelines:

- Patients undergoing Anti-Retroviral viral Therapy (ART): In active and inactive carrierstherapy and universal prophylaxis with antivirals(utilizing the same NAs effective on HBV used in the treatment of HIV infection) are indicated, respectively. In HbsAg-negative/anti-HBc positive subjects, the condition of occult carrier, characterized by HBV DNA positivity in serum and/ or in the liver, has been identified in 35-90% of subjects with HIV co-infection using high sensitivity techniques, and only in 1% of cases with less sensitive techniques. Even in the presence of anecdotal reports of reactivation during immunodepletion and/or of suspension of lamivudine, the risk of sero-reversion appears to be very low (0.23/100 patients/year) and it doesnot therefore justify any prophylaxis but only monitoring [44].

- Patients who do not require ART: In active carriers therapy with interferons or antivirals is indicated. In these subjects treatment should preferably be administered using drugs which do not have any effect on HIV and which do not, in the future, induce resistance to ART Instead, in inactive carriers and in anti-HBc positive subjects monitoring of HBV DNA or HBsAg, respectively, is recommended, with activation of therapy or targeted prophylaxis in the case of reactivation or sero-reversion.

Conclusion

Literature

on hepatitis B in immuno-compromised patients is very

heterogeneous. It refers mainly to the pre-NAs era and the period prior

to the introduction of the modern techniques of determination and

quantification of the viremia, which raises many doubts and

difficulties about the interpretation of the studies and leaves several

aspects still a matter of debate. This encourages a network of

communication and studies, in order to better define the natural

history, the potential risk of hepatitis B and the results of the

various strategies proposed in the management.

Even in the light of such premises today it appears to be justified to propose a rational approach to the problem of hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients, which provides for:a) screening of HBV markers in all subjects starting immunosuppressive therapies and the evaluation of their original liver condition (baseline; b) therapy of active carriers, preferably with third generation NAs; c) prophylaxis, preferentially with a low-cost NA, of inactive carriers and anti-HBc positive patients at risk (onco-hematologic and BMT patients); c) HBV DNA (in inactive overt carriers) or HBsAg (in anti-HBc positive subjects) monitoring of the remaining patients at low risk of reactivation. Finally, in the transplant setting, a precise Donor/Recipient matching should be considered.

Even in the light of such premises today it appears to be justified to propose a rational approach to the problem of hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients, which provides for:a) screening of HBV markers in all subjects starting immunosuppressive therapies and the evaluation of their original liver condition (baseline; b) therapy of active carriers, preferably with third generation NAs; c) prophylaxis, preferentially with a low-cost NA, of inactive carriers and anti-HBc positive patients at risk (onco-hematologic and BMT patients); c) HBV DNA (in inactive overt carriers) or HBsAg (in anti-HBc positive subjects) monitoring of the remaining patients at low risk of reactivation. Finally, in the transplant setting, a precise Donor/Recipient matching should be considered.

References

- Marzano A, Angelucci E, Andreone P, et

al.Prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B in immunocompromised

patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2007 May;39(5):397-408.

- Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR et al.

Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus

infection. J Hepatol 2008;49(4):652-7.

- EASL clinical practice guidelines:

management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2009;50(2):227-42.

- Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson

IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, et al. A treatment algorithm for the

management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:87-106.

- Di Marco V, Marzano A, Lampertico P,

Andreone P, Santantonio T, Almasio PL, et al. Clinical outcome of

HBeAgnegative chronic hepatitis B in relation to virological response

to lamivudine. Hepatology 2004;40:883-91.

- Fung SK, Chae HB, Fontana RJ, Conjeevaram

H, Marrero J, Oberhelman K, et al. Virologic response and resi stance

to adefovir in patients with chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol,

2006;44:283-90.

- Locarnini S, Hatzakis A, Heathcote J,

Keeffe EB, Liang TJ, Mutimer D, et al. Management of antiviral

resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther

2004;9:679-93.

- Carosi G, Rizzetto M. Treatment of

chronic hepatitis B: recommendations from an Italian workshop. Dig

Liver Dis. 2008 Aug;40(8):603-17

- Mutimer D, Dusheiko G, Barrett C,

Grellier L, Ahmed M, Anschuetz G, et al. Lamivudine without HBIg for

prevention of graft reinfection by hepatitis B: Long-term

follow-up.Transplantation 2000;70:809-15.

- Matthews GV, Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini

S, Ayres A, Sasaduesz J, Seaberg E, et al. Characteristics of drug

resistant HBV in an international collaborative study of

HIVHBV-infected individuals on extended lamivudine-therapy. AIDS

2006;20:863-70.

- Lampertico P, Vigano M, Manenti E,

Iavarone M, Lunghi G, Colombo M. Adefovir rapidly suppresses hepatitis

B in HBeAg-negative patients developing genotypic resistance to

lamivudine. Hepatology 2005;42:1414-9.

- Alexopoulos CG, Vaslamatzis M,

Hatzidimitriou G, Prevalence of hepatitis B virus marker positivity and

evolution of hepatitis B virus proȚ le, during chemotherapy, in

patients with solid tumours. B J Cancer 1999;81:69-74.

- Marcucci F, Mele A, Spada E, Candido A,

Bianco E, Pulsoni A, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis B virus

infection in B-cell non-Hodgkin.s lymphoma, Haematologica 2006;91:554-7.

- Takai S, Tsurumi H, Ando K, Kasahara S,

Sawada M, Yamada T, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus

infection in haematological malignancies and liver injury following

chemotherapy. Eur J Hematol 2005;74:158-65.

- Dai MS, Chao TY, Kao WY, Shyu RY, Liu

TM. Delayed hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of

preemptivelamivudine in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus

CHOP. Ann Hematol 2004;83:769-74.

- Hui CK, Cheung WW, Au WY, Lie AK, Zhang

HY, Yueng YH, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation after withdrawal of

pre-emptive lamivudine in patients with haematological malignancy on

completion of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gut 2005;54:1597-603.

- Lau GK, Yiu HH, Fong DY, Cheng HC, Au

WY, Lai LS, et al. Early is superior to deferred pre-emptive lamivudine

therapy for hepatitis B patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Gastroenterology 2003;125:1742-9.

- Kohrt HE, Ouyang DL, Keeffe EB. Systemic

review: Lamivudine prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced reactivation of

chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

2006;24:1003-16.

- Knoll A, Pietrzyk M, Loss M, Goetz WA,

Jilg W. Solid organ transplantation in HBsAg-negative patients with

antibodies to HBV core antigen: Low risk of HBV reactivation.

Transplantation 2005;79:1631-3.

- Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus

infection: Implications in transfusion. Vox Sang 2004;86:83-91.

- Zekri AR, Mohamed WS, Samra MA, Sherif

GM, El-Shehaby AM, El-Sayed MH. Risk factors for cytomegalovirus,

epatiti B and C virus reactivation after bone marrow transplantation.

Transpl Immunol 2004;13:305-11.

- Dickson RC, Terrault NA, Ishitani M,

Reddy KR, Sheiner P, Luketic V, et al. Protective antibody levels and

dose requirements for IV 5% Nabi Hepatitis B immune globulin combined

with lamivudine in liver transplantation for hepatitis B-induced end

stage liver disease. Liver Transpl 2006;12:124-33.

- Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Kanwal F,

Dulai G. HBsAg seropositive status and survival after renal

transplantation: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J

Transplant 2005;5:2913-21.

- Berger A, Preiser W, Kachel HG, Sturmer

M, Doerr HW. HBV reactivation after kidney transplantation. J Clin

Virol 2005;32:162-5.

- Fagiuoli S, Minniti F, Pevere S,

Farinati F, Burra P, Livi U, et al. HBV and HCV infections in heart

transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;20:718-24.

- Zampino R, Marrone A, Ragone E,

Costagliola L, Cirillo G, Karayiannis P, et al. Heart transplantation

in patients with chronic hepatitis B: Clinical evaluation, molecular

analysis and effect of treatment. Transplantation 2005;80:1340-3.

- De Feo TM, Grossi P, Poli F, Mozzi F,

Messa P, Minetti E, et al. Kidney transplantation from anti-HBc

positive donors: Results from a retrospective Italian study.

Transplantation 2006;81:76-80.

- Fabrizi F, Dulai G, Dixit V,

Bunnapradist S, Martin P. Lamivudine for the treatment of hepatitis B

virus-related liver disease after renal transplantation: Meta-analysis

of clinical trials. Transplantation 2004;77:859-64.

- Fabrizi F, Lunghi G, Martin P. Hepatitis

B virus infection in hemodialysis: Recent discoveries. J Nephrol

2002;15:463-8.

- Natov SN, Pereira BJ. Transmission of

viral hepatitis by kidney transplantation. Transplant Infect Dis

2002;4:117-23.

- Berber I, Aydin C, Yigit F, Turkmen F,

Titiz I, Altaca G. The effect of HBsAg-positivity of kidney donors on

long-term patient and graft outcome. Transplant Proc 2005;37:4173-5.

- Marzano A, Lampertico P, Mazzaferro V,

Carenzi S, Vigano M, Romito R, et al. Prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus

recurrence after liver transplantation in carriers of

lamivudine-resistant mutants. Liver Transpl 2005;11:532-8.

- Marzano A, Gaia S, Ghisetti V, Carenzi

S, Premoli A, Debernardi-Venon W, et al. Viral load at the time of

liver transplantation and risk of hepatitis B virus recurrence. Liver

Transpl 2005;11:402-9.

- Manzarbeitia C, Reich DJ, Ortiz JA,

Rothstein KD, Araya VR, Munoz SJ. Safe use of livers from donors with

positive hepatitis B core antibody. Liver Transpl 2002;8:556-61.

- Franchello A, Ghisetti V, Marzano A,

Romagnoli R, Salizzoni M. Transplantation of hepatitis B surface

antigen-positive livers into hepatitis B virus-positive recipients and

the role of hepatitis delta coinfection. Liver Transpl 2005;11:922-8.

- Ghisetti V, Marzano A, Zamboni F, Barbui

A, Franchello A, Gaia S, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in

HBsAg negative patients undergoing liver transplantation: Clinical

significance. Liver Transpl 2004;10:356-62.

- Abdelmalek MF, Pasha TM, Zein NN,

Persing DH, Wiesner RH, Douglas DD. Subclinical reactivation of

hepatitis B virus in liver transplant recipients with past exposure.

Liver Transpl 2003;9:1253-7.

- Vento S, Cainelli F, Longhi MS.

Reactivation of replication of hepatitis B and C viruses after

immunosuppressive therapy: An unresolved issue. Lancet Oncol

2002;3:333-40.

- Esteve M, Saro C, Gonzalez-Huix F,

Suarez F, Forne M, Viver JM. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following

inß iximab therapy in Crohn.s disease patients: Need for primary

prophylaxis. Gut 2004;53:1363-5.

- Zanati SA, Locarnini SA, Dowling JP,

Angus PW, Dudley FJ, Roberts SK. Hepatic failure due to Ț brosing

cholestatic hepatitis in a patient with pre surface mutant hepatitis B

virus and mixed connective tissue disease treated with prednisolone and

chloroquine. J Clin Vir 2004;31:53-7.

- Calabrese LH, Zein NN, Vassilopoulos D.

Hepatitis B reactivation with immunosuppressive therapy in rheumatic

disease: Assessment and preventive strategies. Ann Rheum Dis

2006;65:983-9.

- Buttgereit F, da Silva JA, Boers M,

Burmester GR, Cutolo M, Jacobs J, et al. Standardised nomenclature for

glucocorticoid dosages and glucocorticoid treatment regimens: Current

questions and tentative answers in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis

2002;61:718-22.

- Alberti A, Clumeck N, Collins S, Gerlich

W, Lundgren J, Palù G, et al. Short statement of the Ț rst European

Consensus Conference on the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C in

HIV co-infected patients. J Hepatol 2005;42:615-24.

- Puoti M, Torti C, Bruno R, Filice G,

Carosi G. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B in co-infected

patients. J Hepatol 2006;44:S65-70.

- Firpi R, Nelson D. Management of viral

hepatitis in hematologic malignancies. Blood Rev 2008;22:117-26.

- Katz LH, Fraser A, Gafter-Gvili A,

Leibovici L, Tur-Kaspa R. Lamivudine prevents reactivation of hepatitis

B and reduces mortality in immunosuppressed patients: Systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat 2008;15:89-102.

- Martyak LA, Taqavi E, Saab S. Lamivudine

prophylaxis is effective in reducing hepatitis B reactivation and

reactivationrelated mortality in chemotherapy patients: A

meta-analysis. Liver Int 2007;:28-38.

- Saab S, Dong MH, Joseph TA, Tong MJ,

Hepatitis B prophylaxis in patients undergoing chemotherapy for

lymphoma: A decision analysis model. Hepatology 2007;46:1049-56.

- Yeo W, Chan PK, Ho WM, Zee B, Lam KC,

Lei KL, et al. Lamivudine for the prevention of hepatitis B virus

reactivation in hepatitis B s-antigen seropositive cancer patients

undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy, J Clin Oncol 2004;22:927-34.

- Li YH, He YF, Jiang WQ, Wang FH, Lin XB,

Zhang L, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis reduces the incidence and

severity of hepatitis in hepatitis b virus carriers who receive

chemotherapy for lymphoma. Cancer 2006;106:1320-5.

- Aksoy S, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S,

Dede DS, et al. Rituximab-related viral infections in lymphoma

patients. Leuk Lymph 2007;48:1307-12.

- Targhetta C, Cabras MG, Mamusa AM,

Mascia G, Angelucci E. Hepatitis B virus related disease in isolated

anti-Hepatitis B-core positive lymphoma patients receiving chemo or

chemoimmune therapy. Haematologica 2008;93:951-2.

- Hui CK, Cheung WW, Leung KW, Cheng VC,

Tang BS, Li IW, et al. Outcome and immune reconstitution of HBVspeci Ț

c immunity in patients with reactivation of occult HBV infection after

alemtuzumab-containing chemotherapy regimen. Hepatology 2008;48:1-10.

- Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NWY et al.

Hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved

hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J

Clin Oncology 2009;27(4):605-611.

- Tavil B, Kuskonmaz B, Kasem M, Demir H,

Cetin M, Uckan D. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin in combination with

lamivudine for prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation in children

undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Pediatr Transplant

2006;10:966-9.

- Sobhonslidsuk A, Ungkanont A. A

prophylactic approach for bone marrow transplantation from a hepatitis

B surface antigen-positive donor. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:1138-40.