Received: December 19, 2014

Accepted: March 3, 2015

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2015, 7(1): e2015026, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2015.026

This article is available on PDF format at:

Jonathan Braue1, Thomas Hagele2, Abraham Tareq Yacoub3, Suganya Mannivanan4, Lubomir Sokol5, Frank Glass5 and John N. Greene6

1 University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, 12901 Bruce B. Down Blvd, Tampa, Florida 33612-4742

2

University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Department of

Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 12901 Bruce B. Down Blvd, Tampa,

Florida 33612-4742

3 Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, Florida 33612-9497

4

University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Division of

Infectious Disease and International Medicine, 1 Tampa General Circle,

G323, Tampa, Florida 33612-9497

5 Moffitt Cancer Center, Department of Cutaneous Oncology, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, Florida 33612-9497

6 Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida College of Medicine, 12902 Magnolia Drive, Tampa, Florida 33612-9497

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Secondary syphilis has been known

since the late 19th century as the great imitator; however, some

experts now regard cutaneous lymphoma as the great imitator of skin

disease. Either disease, at times an equally fastidious diagnosis, has

reported to mimic each other even. It is thus vital to consider these

possibilities when presented with a patient demonstrating peculiar skin

lesions. No other manifestation of secondary syphilis may pose such

quandary as a rare case of rupioid syphilis impersonating cutaneous

lymphoma. We present such a case, of a 36-year-old HIV positive male,

misdiagnosed with aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, actually exhibiting

rupioid syphilis thought secondary to immune reconstitution

inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). |

Introduction

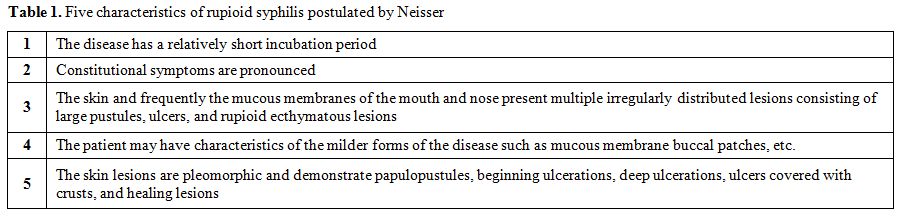

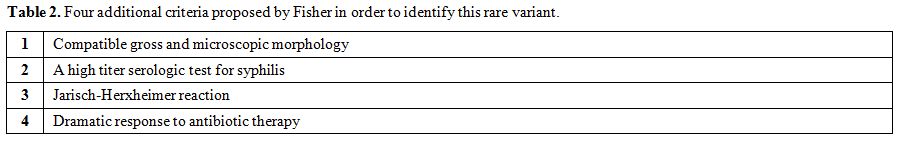

In 1859, the French dermatologist Pierre Bazin first used the term malignant to describe a case of secondary syphilis, and five years later, in a thesis, his student Dubue defined malignant syphilis.[1] Furthermore, in 1896, at the Third International Congress of Dermatology in London, the Danish dermatologist Haslund and German dermatologist Neisser, independently classified malignant syphilis as a rare and ulcerating form of secondary syphilis and not an early form of tertiary syphilis as was previously contemplated.[1-3] Malignant syphilis, also referred in the literature as syphilis maligna praecox, lues maligna, or rupioid syphilis, is defined to present with pleomorphic multiple round to oval papules, papulopustules, or nodules with ulceration, without central clearing, and additionally exhibiting a lamellate brown to black rupioid crust.[4,5] The term rupioid stems from the rupia, or “oyster-like” appearance of these lesions, and, therefore, is the author’s preferred title of this condition. Oddly, diagnosis by skin biopsy in affected patients proves difficult. In general, there is an extreme paucity of spirochetes in the skin lesions and special staining and dark field microscopy may not lead to a histologic diagnosis.[5] To guide the clinical diagnosis, Neisser postulated five characteristics of rupioid syphilis (Table 1).[1] Moreover, in 1969, Fisher et al proposed four additional criteria in order to identify this rare variant (Table 2).[5] This particular expression of secondary syphilis was quite rare prior to the advent of HIV, with an estimated frequency of 0.12-0.36 % and only about two dozen cases published in the English literature prior to 1994.[2] Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, the incidence of rupioid syphilis has been steadily rising, making it a disease of vital recognition for any patient with suspicious cutaneous lesions.[2]

|

Table 1. Five characteristics of rupioid syphilis postulated by Neisser |

|

Table 2. Four additional criteria proposed by Fisher in order to identify this rare variant. |

Only cutaneous lymphoma, with its myriad presentations both

clinically and histologically, could be such a comparably challenging

diagnosis as that of secondary syphilis. In 1975, Abell et al, gathered

histologic data on skin biopsies from 57 patients with serologically

proven secondary syphilis.[6] The most common clinical

diagnosis previous to histologic examination from these biopsies, other

than syphilis, was said to be in order of frequency, pityriasis

lichenoides, psoriasis, eczema, insect bites, sarcoidosis,

leishmaniasis, and lymphoma.[6] Moreover, many reports

of syphilis mimicking mycosis fungoides (MF) have been documented. In

1980, Levin et al described a patient with compelling evidence for the

diagnosis of MF, only to later be revealed as a strange case of

secondary syphilis.[7] Since Levin’s report, there have been other documented cases of secondary syphilis mimicking MF.[8-10]

Our patient highlights similar points, and, in addition, offers an

etiology to the cause of rupioid syphilis in HIV underlining the

importance of a detailed medical history and adequate laboratory tests

in an HIV infected patient.

Case Report

In late July, a 36-year-old African American man with a history of

HIV and remote history of properly treated syphilis, presented to our

institution for a second opinion regarding his recent diagnosis of

peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS). The

patient’s history revealed he had not been on anti-retroviral therapy

(ART) for many years due to adverse effects. During the evaluation by

his outside practitioner, he was

told that his viral load was

“very high”, but uncertain in the number, though his CD4 count was 325

cells/ml. He was thus started on a combination of elvitegravir,

cobicistat, tenofovir, and emtricitabine. Two weeks after restarting

ART, he reported fevers, chills, night sweats and several erupting skin

lesions on his jaw, scalp, nose, legs, and arms. Follow-up CD4 count

revealed a moderate increase up to 450 cells/ml.

In June,

during his initial work-up at an outside facility, a skin biopsy was

done on a right scalp lesion and revealed an atypical lymphohistiocytic

infiltrate in the subcutaneous tissue, consisting mainly of CD3+, CD5+,

CD7+, and CD8+ cells. Histiocytes were positive for CD68 marker, and

the T-cell receptor (TCR) gene was clonally rearranged. Successively, a

computed tomography (CT) scan of his neck, chest, and abdomen

demonstrated several prominent lymph nodes in the neck, axillary, and

inguinal areas, ranging from 14 mm up to 19 mm. A biopsy of the

terminal ileum and of a rectal mass, which revealed on the former CT

scan, were performed. The pathology of the terminal ileum showed an

atypical submucosal lymphoid infiltrate consisting of 50% CD8+ and 50%

CD4+ cells. The biopsy of the rectal mass showed atypical lymphoid

cells in a necrotic background. The bone marrow biopsy was performed

and showed normocellular marrow (40-60% cellularity) with regular

trilinear hematopoiesis. No abnormal lymphoid population was detected

using flow cytometry, and cytogenetics was normal 46, XY. Further

inguinal and peripheral lymph node biopsies failed to show evidence of

lymphoma. The differential at this time consisted of PTCL NOS versus

CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. The patient

underwent port placement and was to begin chemotherapy. It was at this

time that he presented to us.

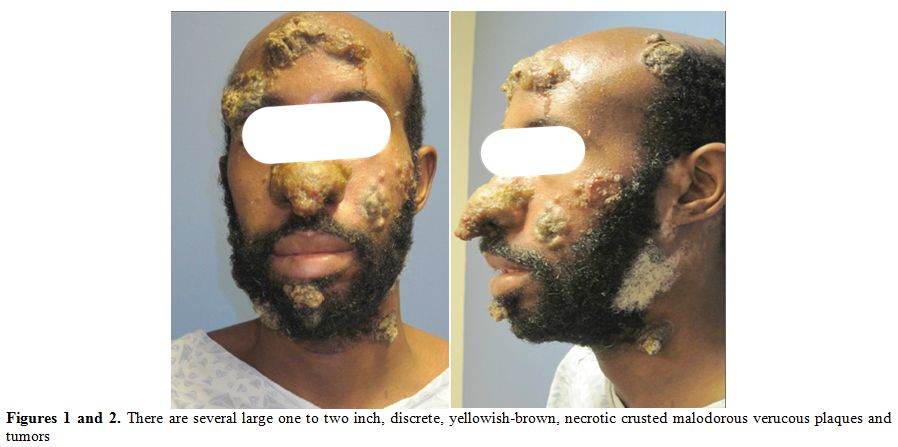

On initial presentation, the patient

exhibited on his nose, forehead, scalp, cheek, neck, and bilateral

upper and lower extremities, several large one to two inch, discrete,

yellowish-brown, necrotic crusted malodorous verrucous plaques and

tumors (Figures 1 and 2). He

reported that the large plaque on his nose was occluding his nares and

draining a foul-smelling brownish fluid, making it difficult for him to

breath. At this time, he was not experiencing fever, chills, or night

sweats, but did continue to endorse some unintentional weight loss. The

lesion located on his right arm was quite painful, making it difficult

to sleep, but there were no intraoral lesions present. At this time,

further skin biopsies were performed. The pathology (Figures 3 A and B)

showed an atypical lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that appeared to be

reactive without clonal etiology. There were areas of necrosis and no

discrete granulomas. The epidermis showed spongiosis, keratinocyte

necrosis; acute inflammatory infiltrate, and pseudo-epitheliomatous

hyperplasia with flow cytometry of the skin specimen showed

predominantly small mature lymphocytes and histiocytes with no clonal

findings and no evidence of T-cell lymphoma. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB),

cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex and varicella zoster viruses, and

Warthin-Starry staining were negative. AFB, fungal, and bacterial

cultures were also negative. Throughout this work-up, the patient

reported that his lesions were only getting worse, and his nasal

breathing problems were also increasing.

|

Figures 1 and 2. There are several large one to two inch, discrete, yellowish-brown, necrotic crusted malodorous verucous plaques and tumors |

| Figure 3. Skin biopsy from anterior scalp lesion. H+E Stain. A: Prominent dermal infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes. Poorly formed granulomas with Giant cells are present. B: A dermal perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate is present. The lymphocytes are predominantly small with mildly irregular nuclear contours. |

After effectively ruling out cutaneous lymphoma, secondary syphilis of the rupioid type became top of our differential. The fluorescent treponemal antibody (FTA-ABS) was positive, and the rapid plasma reagin titer was very highly reactive at 1:1,024. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies were negative. In conjunction with the time course and increase in his CD4 count after starting ART, it was thought that his rupioid syphilis was derived from an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). He was consequently commenced on intravenous penicillin G (IV) 24 million units daily but after about 24 hours from initiation, he developed fever and chills. It was unclear if this was due to an allergic reaction or secondary to a mild Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, which is expected during treatment for rupioid syphilis. However, the dose was decreased and within days, the lesions began resolving and the patients breathing improved. He was treated in this manner for two weeks and then discharged with an additional three weekly injections of intramuscular benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units. The crusted lesions flaked off within a week of treatment. Within several weeks of treatment, all of the cutaneous lesions were resolved, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up without reevaluation of his intra-abdominal lesions.

Discussion

Since the beginning of the 20th

century, when Neisser described 31 patients with rupioid syphilis and

devised clinical criteria to aid in the diagnosis of this ailment,

until the early 1900’s only a handful of cases were reported.[2,4] During this period, rupioid syphilis classically afflicted those who were malnourished, alcoholic, or injection users.[5,8]

However, since the emergence of the HIV-era, the incidence of syphilis,

in general, has been increasing, and with it, the incidence of rupioid

syphilis.[4,5,8] This particular

manifestation of the ancient Treponema remains rare and thus difficult

to recognize and diagnose, especially when disguised so persuasively as

another disorder like cutaneous lymphoma.

There have been many

reports of unusual presentations of secondary syphilis mimicking

cutaneous lymphoma, both clinical and histologically.[6-10]

To our knowledge, there is only a single case that reports a patient

with rupioid syphilis masquerading as mycosis fungoides (MF).[8]

However, our case proves unique in several key points. First, differing

from all of the previous reports, it is not an indolent form of

cutaneous lymphoma like MF that our patient was thought to posses, but

rather a very aggressive form in need of systemic chemotherapy.

Secondly,

and somewhat curiously, the initial TCR gene rearrangement on our

patient did indicate a clonal T-cell proliferation unlike what was

reported in previous cases. Finally, we propose an etiology to our

patient’s eruption of rupioid syphilis, in that it could have been

secondary to an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).

Prior to the 1970’s it was not uncommon for secondary syphilis to be clinically confused with MF.[6,11]

In 1975, Abell et al described several different histologic appearances

in their biopsies, and proposed that the presence of a heavy upper

dermal infiltrate with invasion of mononuclear cells into the epidermis

would simulate MF.[6] They then argued however, that

the usual presence of plasma cells and lack of large hyperchromatic

mononuclear cells with crenate nuclei would speak against a diagnosis

of MF and support secondary syphilis. Yet, there was a single case

where a small population of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells was

present amongst a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, thus at first glance

being very easily misconstrued as cutaneous lymphoma.[6] Moreover, several other cases since Abell’s have made equally compelling histological arguments for a diagnosis of MF.[7-10]

However, when reported, the T-cell receptor (TCR) gamma/beta gene

rearrangement assay was negative, and in some of the cases the

Warthin-Starry stain demonstrated spirochetes.[8,9] In

our patient, MF was not a consideration based on the rapidity of the

eruption and more aggressive pathology seen from the skin biopsies. For

this reason, it is vital to consider alternative diagnosis and repeat

of key laboratory work-up prior to initiating highly toxic

chemotherapy. Why then did out patient’s skin express such an

aggressive pathology, and why was the initial peripheral flow cytometry

indicative of a clonal T-cell expansion? Perhaps it was truly related

to a rebound hunger from his immune system following initiation of ART

and thus an underlying IRIS.

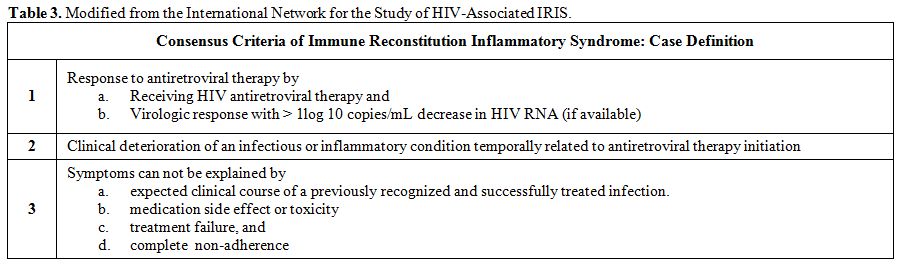

IRIS is a paradoxical immunological phenomenon, which occurs in patients whom are recovering from an immunocompromised state.[12]

In the HIV affected individual, this can occur in up to 25% within a

few months of being placed on ART, with additional risk incurred when

placed on ART late in the disease course.[12-15]

Attempts have been made to tabulate clinical criteria to diagnose IRIS,

as there are no currently accepted laboratory data that can render a

diagnosis. In 2004, French et al decreed a set of criteria for this

purpose.[13] Our patient met the minimum criteria for

a diagnosis of IRIS based on French et al’s publication, on the basis

that he did respond to antiretroviral therapy, he did have a very

atypical presentation of his infection, his CD4+ count raised, and the

increase in the immune response was directed at his syphilis. Moreover,

the atypical lymphocytic infiltrate seen in his skin, a diagnostic

criterion, could certainly be the reason for the aggressive cutaneous

lymphoma mimicry. Additionally, French et al and Martin-Blondel et al

discuss risk factors for development of IRIS, and although our

patient’s CD4 count was not critically low prior to the induction of

ART, many of the other risk factors were met, such as the high pre-ART

viral load, strong response to ART based on increase in CD4 counts,

ART-naïve patient, black ethnicity, and his subclinical infection.[13,16]

Furthermore,

most recently the consensus criteria for the diagnosis of IRIS were put

forth by the International Network for the Study of HIV-associated IRIS

(Table 3).[12]

Our patient met many of these criteria, and although he did not have

follow-up HIV RNA titers, there was a clear response to treatment as

his CD4 count increased by nearly 175 cells/ml. It is thus very likely

that our patient did suffer from IRIS after initiating ART, which could

have led to the initial positive peripheral flow cytometry and the

peculiar pathology demonstrated from his multiple biopsies.

|

Table 3. Modified from the International Network for the Study of HIV-Associated IRIS. |

Conclusion

Because of the similar appearance of rupioid syphilis and cutaneous lymphoma, this case validates the notion of truly combining the clinical and pathologic information to distinguish the two entities. Our patient could have significantly worsened if he had been placed on chemotherapy rather than properly treated with antibiotics. Additionally, through a diagnosis of IRIS, we suggest a plausible relationship between our patient’s rare presentation of rupioid syphilis and the imitation that took place.

References

.

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

. .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

. [TOP]