Received: January 15, 2015

Accepted: March 18, 2015

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2015, 7(1): e2015031, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2015.031

This article is available on PDF format at:

Ludmila Mourão Xavier Gomes1, Thiago Luis de Andrade Barbosa2, Elen Débora Souza Vieira2, Lara Jhulian Tolentino Vieira2, Karla Patrícia Ataíde Nery Castro2, Igor Alcântara Pereira2, Antônio Prates Caldeira2, Heloísa de Carvalho Torres3 and Marcos Borato Viana1

1 Núcleo de Ações e Pesquisa em Apoio Diagnóstico, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

2 Department of Medicine, State University of Montes Claros, Montes Claros, Brazil

3 Department of Applied Nursing, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Introduction. Despite advances

in the management of sickle cell disease, gaps still exist in the

training of primary healthcare professionals for monitoring patients

with the disease. Objective. To assess the perception of community healthcare workers about the care and monitoring of patients with sickle cell disease after an educational intervention. Method. This exploratory, descriptive, and the qualitative study was conducted in Montes Claros, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The intervention involved the educational training of community healthcare workers from the Family Health Program of the Brazilian Unified Health System. The focus group technique was used to collect the data. The following topics were covered in the discussion: assessment of educational workshops, changes observed in the perception of professionals after training, profile of home visits, and access to and provision of basic healthcare services to individuals with sickle cell disease. The discussions were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data were subjected to content analysis and empirically organized into two categories. Results. Changes in the healthcare practices of community health workers were observed after the educational intervention. The prioritization of healthcare services for patients with sickle cell disease and monitoring of clinical warning signs in healthcare units were observed. Furthermore, changes were observed in the profile of home visits to patients, which were performed using a script provided in the educational intervention. Conclusion. The educational intervention significantly changed the work process of community health workers concerning patient monitoring in primary healthcare. |

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most important hemoglobinopathy

worldwide and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.[1] In

Brazil, SCD is a relevant public health topic, considering the

epidemiological, clinical, economic, and social issues involved. The

prevalence of sickle cell trait in Brazil is estimated to be between 2%

and 8%,[2] depending on the ethnic composition of the regional

populations. The incidence of SCD in Minas Gerais, a Southeastern

state, is 1:1,400 newborns, according to the Newborn Screening Program

(NSP-MG).[3]

The results of the NSP-MG have been rewarding, but

many challenges remain regarding patient care, including the training

of healthcare professionals in educational activities and the provision

of continuous patient care to reduce morbidity and mortality.[3,4]

Research conducted in Minas Gerais showed poor knowledge of primary

care professionals about many aspects of SCD. Poor knowledge probably

reflects badly on the quality of healthcare provided to people with SCD

and their families.[5]

One study that evaluated the perception of

patients with SCD identified several limitations related to providing

primary healthcare to them. These limitations included restricted

access to healthcare services, lack of communication between primary

and secondary healthcare professionals, and lack of confidence in the

ability of primary care professionals to accurately provide information

related to the disease.[6]

Experiences of educational

interventions for primary healthcare professionals about SCD are

scanty. Additionally, they had limited goals such as communication of

newborn screening results[7] and communication skills to offer prenatal

screening for SCD and thalassemia.[8] There are no studies of

educational interventions targeting primary healthcare professionals to

address general care to patients with SCD.

In Brazil, the Family

Health Program has been implemented to strengthen primary healthcare

and reorganize the assistance model in the Brazilian Health System

(Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS). Considering its principles and the

organization of its work processes, the Family Health Program provides

conditions to mitigate the indicators of suffering caused by chronic

diseases such as SCD. Moreover, the Program is characterized by the

integrated work of a multidisciplinary team comprising doctors, nurses,

nurse technicians, and community health workers.[9,10] Community health

workers are essential for the Family Health Program because they reside

in the same area where they work, conduct home visits, and so they can

fully understand the community’s health problems, way of life, and

culture.[11] Therefore, these workers require clear and objective

information from the technical–scientific area to guide community-based

activities,[12,13] and training of these professionals is crucial.

The

aim of this study was to analyze the perception of community primary

healthcare workers about the care and monitoring of individuals with

SCD after an educational intervention.

Methods

This exploratory, descriptive, and qualitative study was conducted

in basic healthcare units of Montes Claros, state of Minas Gerais,

Brazil. Montes Claros is situated in a region with a high prevalence of

SCD. The study was conducted after the educational intervention for

community health workers.

Educational intervention.

The intervention consisted of the training of community health agents

in the Family Health Program on the primary care and monitoring of

individuals with SCD. It was conducted by three nurses who were

previously trained via a 90-hour distance learning course over a

3-month period. Activities were conducted in the form of active

methodologies such as case studies, meetings, stage plays, and

parodies.

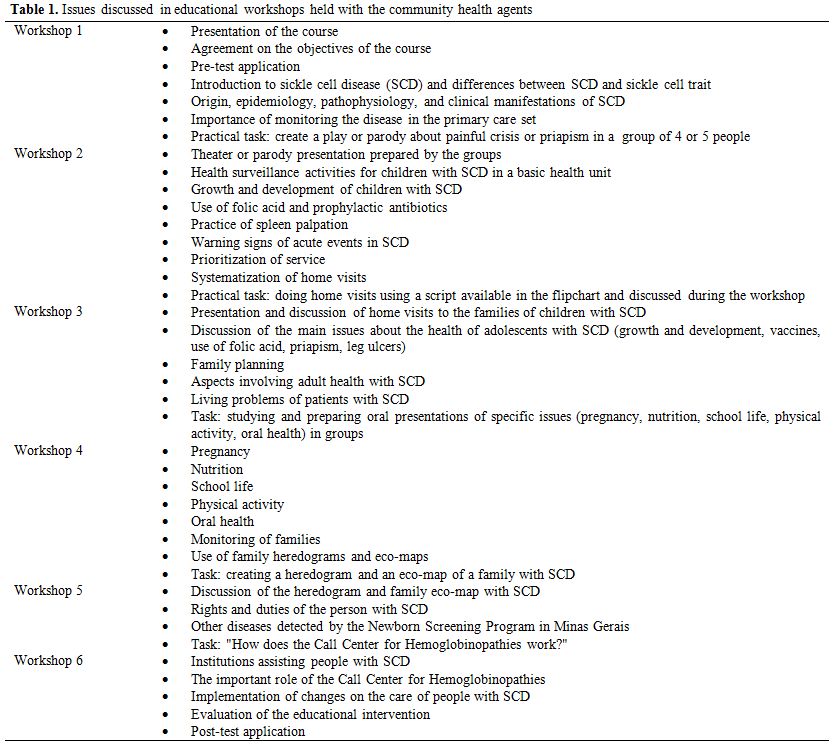

The contents and design of the program are depicted in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Issues discussed in educational workshops held with the community health agents |

The

educational intervention lasted 40 hours: 30 hours in the classroom and

10 hours outside the classroom. Six 5-hour meetings were conducted with

healthcare professionals at intervals of 7 days. After each workshop,

the professionals were assigned homework related to the topics, which

would be addressed in the subsequent workshop.

On completion of

training, two visits were made to healthcare units and involved

discussions on the main topics and guidance on patient monitoring.

A

total of 68 community health agents who assisted patients with SCD and

were from six basic healthcare units were trained. Medical records from

the NSP-MG were used. In addition, each healthcare team was

interrogated about the presence of individuals with SCD in each

jurisdiction.

Participants.

Three months after the intervention, the trained community health

agents were invited to participate in a meeting in a room provided by

the Health Department of Montes Claros. The professionals were selected

on the basis of the following criteria: (i) worked in the Family Health

Program during the study period, i.e. they were not on vacation or work

leave; (ii) their jurisdiction assisted patients with SCD; (iii) they

passed the course with a minimum attendance of 80%; and (iv) they

agreed to participate in the study. Among the 68 trained community

health agents, 27 worked in jurisdictions containing patients with SCD,

and two refused to participate in the study. Consequently, 25 community

health workers were selected to participate in this study.

Data

collection. The focus group technique was used, allowing interaction

and discussions of aspects related to training and changes implemented

in daily activities involving patient care and monitoring.[14] For the

focus discussion, a moderator and two observers who had not

participated in the educational intervention were present. The focus

groups sessions lasted no more than a hundred minutes and used a plan

that included the following topics: assessment of educational

workshops, changes observed in the professionals after training,

profile of home visits, access to and provision of basic healthcare to

individuals with SCD. The discussions were tape recorded and later

transcribed verbatim. The focus sessions were conducted with two

groups, one with 12 participants and the other with 13. The

professionals were allocated to each focus group on the basis of their

availability on previously scheduled dates. Each group participated in

only one focus session. The number of groups formed for the focus

sessions allowed the data to reach saturation range, ensuring that no

new or relevant data were missing when data collection was completed.

Analysis of the data.

The data were subjected to thematic content analysis according to the

following steps: preanalysis, content analysis, processing of the

results, and interpretation.[15] Subsequently, the data were organized

into two empirical categories. Statements from participants were

identified by letter codes accompanied by Arabic numerals. The two

focus groups were designated G1 and G2, and participants received a

code with the letter P.

Ethical aspects.

The confidentiality and anonymity of study participants were guaranteed

throughout the study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics

Committee and was registered in the Brazilian National Council of

Research Ethics under protocol CAAE-0683.0.203.000-11.

Results

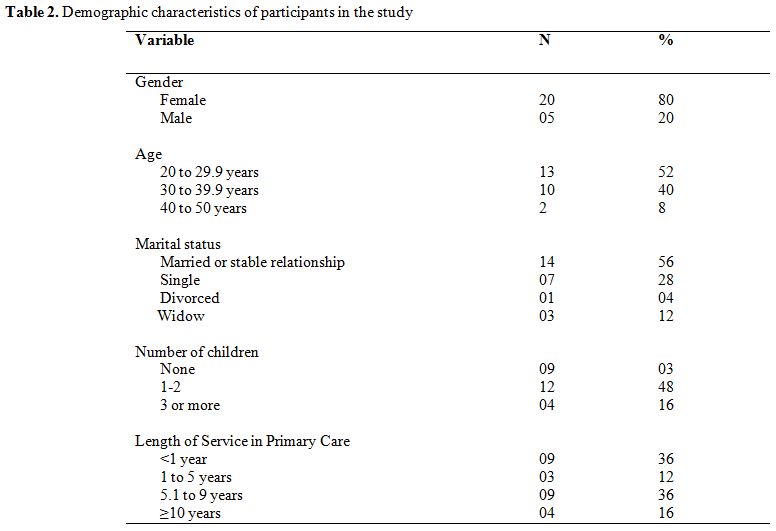

The profile of the 25 professionals is presented in Table 2.

|

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants in the study |

In the focus group, two categories emerged based on the

participants’ statements, as follows: “perception of the educational

intervention” and “training for the promotion of changes in the work of

the professionals.”

Perception of educational intervention.

In this category, the professionals discussed the topics and evaluated

training performed. The educational intervention received a positive

assessment from participants, and they gained deeper knowledge about

different aspects of patient care and monitoring:

“Training

was great, since I had the freedom to play, role play, relax, and

clarify many topics. On our own, we were looking for knowledge about

the disease through the problems we encounter in our daily lives.” G2P4

“We

didn't know about priapism, wounds, the natural history of the disease,

the age of each medication, electrophoresis, and enlarged spleen.”

G2P10 and G2P8

Community health workers covered many topics

related to SCD that they were unaware of; these topics were addressed

in workshops. Negative experiences prior to training were mentioned by

the professionals. Among these, the most important was the lack of

awareness about priapism:

“I had

a very bad negative experience, I went to the house of a young man with

SCD who had an erection at the time of the visit. I left in a hurry

because I didn't know what priapism was. Today I know how to handle

this situation.” G2P10

It was noted that before the

intervention, some professionals stated that they were unaware on how

to manage patients with SCD in healthcare units. The course taught them

how to monitor patients, and the professionals considered the

educational intervention to be relevant to their everyday practice:

“This

course was very important to our practice. By knowing all these

aspects, now we can take better care of the person who has this

disease. Now we pay more attention when a person with SCD arrives in

our unit.” G1P1 and G1P7

“The

course made me think about my own work. I didn't pay much attention to

my patients SCD, but the course awakened my interest in caring.” GP1P2

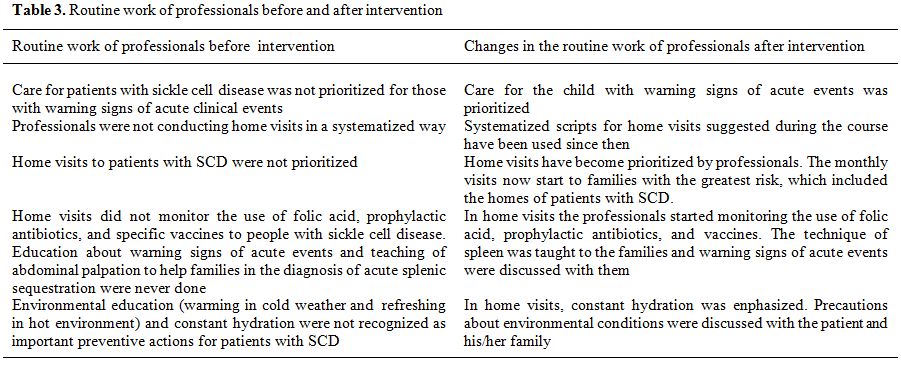

Training to promote changes in the routine work of professionals. Of note, this category included changes implemented by community health agents in their practice after training (Table 3).

They discussed changes in areas such as the prioritization of services,

treatment of new patients, home visit routines, and monitoring of

specific outcomes of patients with SCD. These changes are described

below as subunits of this thematic category.

|

Table 3. Routine work of professionals before and after intervention |

Subtopic: Prioritizing care and treating new patients in the health unit.

Prior to training, healthcare professionals lacked knowledge regarding

the need for prioritizing the care for patients with SCD. They were not

able to understand why mothers of children with the disease were so

critical regarding delays in care for their children and kept insisting

on it to be prioritized:

“It was

in the course that I understood the issue of priority of care. I

started thinking about the mother in my area who has two boys with SCD,

and who comes to the unit and requests her children to be assisted

quickly, unlike other mothers of children who do not have SCD.” G1P10

After

training, the professionals stated that they prioritized care for the

child visiting their unit with warning signs. Furthermore, they

promptly provided humanized care services to individuals with SCD.

“When

the mother comes in, I inquire whether the child has fever, because it

is a risk situation. I also note if the child has pain in the belly,

which can be a problem in the spleen.” GP2P12, G2P8.

Disease

surveillance was performed for every child who visited the healthcare

unit to have anthropometric measurements. In cases where the child had

any health problems or warning signs, health services were performed

promptly:

“The child came to

get weighed and was complaining of fever. So I went and talked to the

doctor. Then the child was examined promptly and the problem was

solved.” GP2P4

Subtopic: changes in the home visit routine.

The main changes referred to by the professionals occurred in home

visits, which were performed using systematized scripts introduced in

the course. Community health agents reported that home visits to

patients with SCD became more time consuming because these

professionals were concerned about evaluating other health aspects and

providing targeted orientation. In addition, the visits became

prioritized, i.e., the professionals made their monthly visits starting

with families with the greatest risk, which included the homes of

patients with SCD:

“The visit

takes much longer. I see if the child in my area is taking folic acid

and antibiotics to prevent complications and remember of the

vaccination programs. I teach them about palpating the spleen and

warning signs. I didn't do this prior to the course.” G1P11

According

to the professionals, the primary change in home visits after training

was monitoring the use of folic acid, prophylactic antibiotics, and

vaccines in patients as well as teaching them how to palpate the spleen

and diagnose warning signs.

In home visits, orientations on

precautions about environmental conditions were conducted, and the need

for constant hydration was also taught, improving care for her child:

“In

one case, the mother worked by selling door-to-door and used to take

the child with her, exposing the child to the sun, which in turn led to

bouts of pain. So I told the mother about the risk of dehydration, and

now she is avoiding taking the child with her, and always hydrates her,

and this is the result of the course. G1P9

Discussion

The educational intervention received a positive evaluation from

community health agents. In addition, the intervention produced changes

in the daily work of these professionals.

Because of its dialectic

and problem-based approach as well as the use of various educational

resources that allowed participants to interact, the educational

intervention increased awareness of community health agents about the

care and monitoring of individuals with SCD. During training workshops,

the professionals reflected on their role in patient care. The

dialectic approach of educational activities provided individuals with

the opportunity of self-reflection and to consider themselves as

promoters of change. In this sense, the educational intervention aimed

to contribute to the pursuit of transformation, and changes were

produced following training.[16]

The experiences

and problems described by healthcare workers during professional life

in the health team redirected their attention to training with the

purpose of improving care. In this context, continuing education is

considered important and is understood as “learning at work, in which

learning and teaching are incorporated into the daily lives of

organizations and work”.[17] The aim of continuing

education is the training of health workers, considering their own

experiences and the problems they face.

In the perception of

these professionals, the educational intervention led to changes in

their healthcare practices. One of these changes was the prioritization

of care for patients with SCD showing warning signs of acute events,

such as fever, pain, sudden increase in pallor, worsening jaundice,

abdominal distension, enlarged spleen or liver, cough or difficulty in

breathing, priapism, neurological changes, inability to swallow

liquids, dehydration, vomiting, and hematuria.

The

professionals’ statements indicated that mothers of children with SCD

were more demanding and required immediate care for their children.

This fact can be explained by the occurrence of vaso-occlusive

phenomena that can lead to serious complications such as stroke when a

child showing warning signs is not treated quickly. Knowledge derived

from the educational intervention allowed the provision of better care

because it changed the professionals' perception of the mothers who

demand immediate care for their children during emergencies. In their

daily work, community health agents alerted other team members to

expedite care as soon as they detected warning signs.

A relevant

point in the professionals’ statements was related to patient

monitoring. The professionals were aware of the warning signs and

always interrogated the responsible parties about these signs. This

happened, for example, when the child visited to the clinic for

anthropometric measurements and any complaints were noted by the

professionals or reported by the mother or guardian. A routine

appointment can then become an urgent situation for community health

workers.

Surveillance activities undertaken by community agents

are not restricted to the health units. A study of primary healthcare

professionals in Brazil found that community workers have acted more

intensely in the areas of education and coordination of information

between the healthcare team and service users. Moreover, they performed

various outdoor activities in streets, homes, and reference points in

the community. Home visits were the main activity of these

professionals.[18] Another study found that home

visit procedures conducted by community health workers were not

standardized and were defined by each professional. Moreover, home

visits are scheduled on the basis of their experience and physical

location within each service region. Home visits, therefore, become

bureaucratic reproductions of medical consultations, where forms are

completed and routine updates are provided, limiting the establishment

of a relationship between the healthcare team and service users.[19]

In

patients with SCD, patient monitoring through regular, targeted home

visits is essential to achieve more effective therapeutic results. The

results of the present study showed that home visits became

systematized and targeted to patients with SCD after adoption of a

script provided in the educational intervention. Moreover, changes were

observed in the prioritization of home visits to patients with SCD

because these families are at a greater risk. In this respect, the

prioritization of home visits benefited not only individuals with SCD

but also families that constituted risk groups. In the systematized

home visits, the professionals guided patients on the use of folic

acid, prophylactic antibiotics, and vaccines and taught family members

how to palpate the child’s spleen. Monitoring the use of folic acid in

home visits is necessary to cope with accelerated erythropoiesis, a

specific feature of the disease.[20] Adherence to drug therapy is a relevant issue in patient monitoring, as previously reported.[21,22]

When community health agents noted poor adherence to the recommended

drug therapy in home visits, these visits became more time consuming

because of the constant need to explain the importance of preventive

healthcare measures to families.

The vaccination status should be

monitored during visits both in relation to the basic vaccination

schedules and the vaccines recommended for SCD. Previous studies

indicated that vaccination coverage in relation to the basic calendar

varied between 65% and 100%.[4,23]

However, this is not the reality for all vaccines. In Brazil, vaccines

for pneumococcus and meningococcus were included in the basic

immunization schedule in 2010. Prior to this date, two studies in the

Brazilian states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo showed that 43.8%

and 50% of children with SCD, respectively, had incomplete immunization

against pneumococcus.[4,24] A study

in London found that immunization against encapsulated bacteria and the

flu virus was also precarious among adults and children with SCD.[25] In Madrid, the regular vaccine coverage was 85%. It was 50% for flu virus and 15% for hepatitis A.[26]

Home

visits are also conducive to teaching parents how to palpate the spleen

for the early diagnosis of acute splenic sequestration. Instructing

parents on this technique can decrease mortality, considering that this

outcome can quickly lead to death. Other educational activities

conducted by these professionals also cover environmental education and

the perception of warning signs. Families are instructed to keep

patients hydrated and away from adverse environmental conditions, such

as extreme heat and cold. The diagnosis of warning signs allows parents

to identify changes that demand emergency care considering the level of

complexity required. This information may help reduce patient mortality

and prevent sickle cell crises.

The limitations of the present

study are related to data collection. The focus group has limited

ability to make inferences about large population groups and cannot

test hypotheses in experiments.[14] Another

limitation derives from the lack of interviews with the same

participants to compare individualized results of the focus

discussions. In this respect, participants may change their opinions

during the focus discussions because of the positioning of the

researchers about sensitive issues. In addition, the effects of

training community agents on patients' health were not assessed because

these effects were not included in the study objectives.

Conclusion

The educational intervention on SCD produced changes in the

attitudes of healthcare professionals to improve the quality of care

provided to individuals with SCD. Knowledge acquired in training

changed attitudes and improved their skills.

Based on these

results, we suggest the widespread training of community health workers

who treat SCD patients in their service area. The educational

intervention studies that include higher-level primary healthcare

professionals are also recommended.

Considering the limited

knowledge about SCD and primary healthcare, further studies are

recommended, particularly those that directly assess the effects of

training on the health of patients with SCD.

Acknowledgements

References

.

. .

.  .

. .

.  .

. .

.  .

.  .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

.  .

. .

.  .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

.[TOP]