Received: August 11, 2015

Accepted: November 11, 2015

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016007, DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2016.007

This article is available on PDF format at:

| This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

|

Abstract Background and Objectives: Hepatitis

C virus (HCV) is a major health problem in Egypt with its prevalence

estimated to be 14.7% among the general population in 2008. Patients

receiving frequent blood transfusions like those with sickle cell

disease (SCD) are more exposed to the risk of acquiring HCV. IL28B gene

polymorphisms have been associated with spontaneous HCV clearance. This

study aims to determine the prevalence of HCV infection among children

with SCD and to investigate the relation between IL28B gene

polymorphisms and spontaneous HCV clearance. Methods: Seventy SCD patients were screened for HCV antibody. HCV-positive patients were tested for the level of HCV RNA using quantitative real-time PCR. IL28B polymorphisms (rs 12979860 SNP and rs 12980275 SNP) were detected using TaqMan QRT-PCR and sequence-specific primers PCR respectively. Results: Sixteen patients (23%) were HCV antibody positive, 9 of them (56.3%) had undetectable HCV RNA in serum, and 7 (43.7%) had persistent viremia. Genotypes CC/CT/TT of rs12979860 were found in 30 (42.9%), 29 (41.4%) and 11 (15.7%) patients and rs12980275 AA/AG/GG were found in 8 (11.4%), 59 (84.3%) and 3 (4.3%) patients. There was no significant difference in the frequency of IL28B (rs 12979860 and rs12980275) genotypes among HCV patients who cleared the virus and those with persistent viremia (p=0.308 and 0.724 respectively). Conclusion: Egyptian SCD patients have a high prevalence of HCV. Multi-transfused patients still exposed to the risk of transmission of HCV. IL28B gene polymorphismsare not associated with spontaneous clearance of HCV in this cohort of Egyptian children with SCD. |

Introduction

Egypt has the highest hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence worldwide.[1] The prevalence of HCV in Egypt is found to be 14.7% among the general population in the year 2008.[2]

HCV prevalence is even higher among hospitalized patients and special

clinical populations who have an increased risk of exposure to HCV like

multi-transfused patients, thalassemic patients, and patients on

hemodialysis.[3] The prevalence of HCV among Brazilian sickle cell disease (SCD) patients was found to be 14%.[4]

Again, a study from the USA found that 22% of SCD patients were

HCV-antibody positive. HCV positivity was most prevalent (58%) among

patients whom blood were drawn before 1992 when testing of all blood

donors in the USA became mandatory.[5] To date, the prevalence of HCV among SCD patients in Egypt is not known.

During the natural course of HCV, about 15% of patients show spontaneous viral clearance without treatment.[6]

HCV spontaneous clearance was defined as the lack of HCV-RNA detection

in the serum of the patient in the presence of a positive antibody

response and absence of antiviral therapy.[7] Factors

affecting viral clearance include age, gender, race, level of viremia,

alcohol intake, and HCV genotype. Genetic studies showed that single

nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the IL28B gene, which encodes

interferon (IFN)-λ-3 are associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.[8] Among the most significant SNPs were rs12979860 and rs12980275.[9-11]

The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of HCV infection

and IL28B gene polymorphisms among Egyptian children with SCD and to

explore the possible relation between IL28B SNPs (rs12979860 and

rs12980275) and spontaneous viral clearance.

Patients and Methods

Patients and Methods.

Patients: This cross-sectional study included 70 Egyptian children with

SCD. The mean age of the patients was 10.2±4.5 years. They were 37

(52.8%) females and 33 (47.2%) males. Patients were consecutively

invited to participate in the study during their regular follow-up

visits at Pediatric Hematology Clinic, New Children Hospital, Cairo

University. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kasr

Al-Ainy School of Medicine, Cairo University and patients were

recruited after informed consents were freely obtained from their

guardians.

In our resource-limited setting, SCD patients are not

routinely or regularly screened for HCV. Therefore, during recruitment

of the patients, their HCV status was not known, and none of the

patients received antiviral treatment. Patients’ records were reviewed

for the frequency of blood transfusion per year in the 12 months

preceding the enrollment. Laboratory testing included complete blood

count (CBC), reticulocyte count, Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and

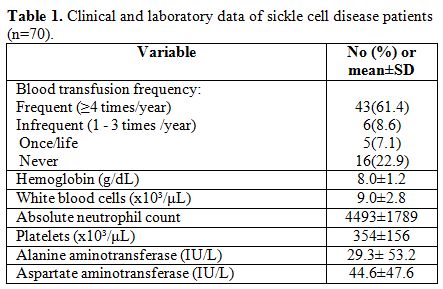

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. Table 1

shows clinical and laboratory data of the patients. Patients were

screened for HCV antibodies, and then quantification of HCV RNA in

serum for patients who were HCV antibody positive was done. To estimate

the frequencies of the IL28B genotypes in Egyptians, the SNPs

rs12979860 C/T SNP and rs12980275 A/G SNP were genotyped in the whole

group of SCD patients.

|

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory data of sickle cell disease patients (n=70). |

Methods:

Serum samples were tested for HCV antibody using a third generation

enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Ortho HCV 3.0 ELISA test system, Ortho

Clinical Diagnostics Inc., Raritan, NJ, USA).

HCV RNA was

quantified using a commercial real-time RT-PCR assay (RealTime™ HCV,

Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA) as specified by the

manufacturer. The detection limit was 12 IU/mL.

For detection of

IL28B polymorphisms, DNA was extracted using AxyPrep Blood Genomic DNA

Miniprep Kit (Axygen Biosciences, USA). IL28B polymorphisms rs 12979860

C/T genotyping was performed using the ABI TaqMan allelic

discrimination kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA)

as described before.[12]

The sequence of the used primers was: Forward 5'-TGCCTGTCGTGTACTGAACCA-3' and Reverse 5'-GAGCGCGGAGTGCAATTC-3'.

The

sequences of the Taqman probes were: Probe for the C allele

TGGTTCGCGCCTTC (VIC ™-labeled) and Probe for the T allele

CTGGTTCACGCCTTC (FAM ™-labeled).

The PCR reaction was carried out

in a total volume of 25µL. The following amplification protocol was

used: pre-incubation at 50°C for 2 minutes and then 95°C for 10

minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds,

and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 minute.

The sequence specific primer -PCR was applied for genotyping IL28B SNP rs12980275A/G polymorphism as described previously.[13] A common reverse primer and two sequence-specific forward primers were used.

Gen

(antisense) 5'-ATGATCATAGCTCATTGCAGC-3' A allele-specific (sense)

5'-AGAAGTCAAATTCCTAGAAAC A-3' G allele-specific (sense)

5'-AGAAGTCAAATTCCTAGAAAC G-3'. Cycling condition was denaturation for 1

minute at 95°C, followed by 46 cycles of amplification; denaturation

for15 seconds at 95°C, annealing for 30 seconds at 50°C and extension

for 30 seconds at 72°C. In the last cycle, the extension was prolonged

to 7 minutes at 72°C. An amplification product of 393 bp was detected.

Statistical Methods:

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)

version 21. Numerical data were expressed as mean ±standard deviation

(SD) and compared by student’s t-test. Qualitative data were expressed

as frequency and percentage and compared by Chi-square test or Fisher’s

exact test as appropriate. Odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence

interval (CI) were used for risk estimation. All p-values are

two-sided. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Screening of SCD patients for HCV antibody revealed that 16 (23%)

patients were positive for HCV antibodies. HCV antibody-positive

patients had significantly higher AST and ALT levels (p= 0.002 and

˂0.001, respectively) compared to HCV antibody-negative patients.

HCV

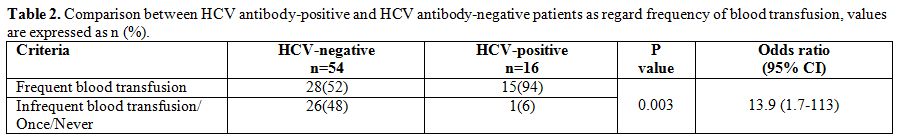

antibody-positive patients had a history of significantly more frequent

blood transfusion compared to HCV antibody-negative patients (p=

0.003). Patients who were receiving a frequent blood transfusion (≥4

times/year) had about 14-fold increased risk to be infected with HCV (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Comparison between HCV antibody-positive and HCV antibody-negative patients as regard frequency of blood transfusion, values are expressed as n (%). |

Among HCV antibody-positive patients (n=16), 9 patients

(56.3%) had undetectable HCV RNA in serum (spontaneously cleared) and 7

patients (43.7%) were non-cleared. HCV non-cleared patients had

significantly higher AST and ALT levels (p= 0.012 and 0.023,

respectively) compared to patients with spontaneous virus clearance.

Genotyping

of SCD patients for IL28B rs 12979860 C/T polymorphism revealed that;

the wild type (CC) was detected in 30 patients (42.9%), heterozygous

genotype (CT) was detected in 29 patients (41.4%), and the homozygous

genotype (TT) was detected in 11 patients (15.7%). The frequency of the

wild allele (C) was 0.64, and the frequency of the mutant allele (T)

was 0.36.

Genotyping of SCD patients for IL28B rs12980275 A/G

polymorphism revealed that; the wild type (AA) was detected in 8

patients (11.4%), heterozygous genotype (AG) was detected in 59

patients (84.3%), and the homozygous genotype (GG) was detected in 3

patients (4.3%). The frequency of the wild allele (A) was 0.54, and the

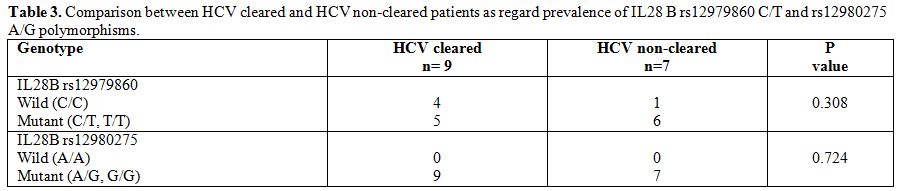

frequency of the mutant allele (G) was 0.46. To analyze the impact of

polymorphisms of IL28B gene on HCV clearance, the prevalence of

rs12979860 C/T and rs12980275 A/G polymorphisms was compared between

patients spontaneously clearing and patients not clearing HCV (Table 3), and no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups as regard prevalence of polymorphisms.

|

Table 3. Comparison between HCV cleared and HCV non-cleared patients as regard prevalence of IL28 B rs12979860 C/T and rs12980275 A/G polymorphisms. |

Discussion

The prevalence of HCV among SCD patients in Egypt is not known. The

present study is the first to investigate HCV prevalence among Egyptian

SCD patients that is found to be 23%. Previous studies in Egypt

revealed that HCV prevalence is high among all special clinical

population groups like hemodialysis patients (35%),[14] hemophilic children (40%),[15] multi-transfused thalassemic patients (40.5%),[16] non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients (43%)[17] and hospitalized patients referred for bone marrow examination (42%).[18]

Hospitalization, repeated blood transfusions, invasive procedures,

injections and shared dialysis machines are common risk factors for HCV

infection among these group of patients. In this study, HCV

antibody-positive patients received blood transfusion more frequently

than HCV antibody-negative patient. Although the incidence of

transfusion-acquired infections has significantly decreased in recent

years because of more effective donor screening methods, the risk is

still present, especially in multi-transfused patients.[19]

At Cairo University blood bank, donated blood is routinely screened for

HCV using a third generation EIA. The more sensitive molecular methods

utilizing nucleic acid amplification technology are not used due to

limited resources. Previous studies have shown that the number of

transfusions was directly correlated with the HCV antibody positivity.

Patients who received 10 or more blood units had significantly higher

incidence of anti-HCV markers than those receiving less than ten units

of blood products.[5] In the current study, patients

who were receiving a frequent blood transfusion (≥4 times/year) had

about 14-fold increased risk to be infected with HCV.

Hepatitis

C leads to persistent infection in a high proportion of infected

individuals, and can progress to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and

hepatocellular carcinoma. HCV spontaneous clearance was defined as the

lack of HCV-RNA detection in the serum of the patient in the presence

of a positive antibody response and absence of antiviral therapy.[7]

In the current study, 56.3% of HCV positive patients spontaneously

cleared the virus. During the natural course of HCV, about 15% of

patients showed spontaneous viral clearance without treatment.[6]

As observed in the current study, higher rates of spontaneous

resolution have been found in children. In a prospective study

including 67 patients with chronic HCV, infection due to blood

transfusion at a mean age of 2.8 years, the infection resolved in 30

patients (45%) after a mean follow-up of 20 years; of the remaining 37

patients, only 1 had abnormal liver enzymes, and only 3 showed signs of

histologic damage.[20] Factors responsible for

age-related differences in the clinical course of chronic HCV infection

may include, structural and/or immunologic differences between children

and adults including less availability of antioxidizing agents and fat

infiltration of adult liver.[21]

Ethnic differences in the frequency of virus clearance suggest that host genetic variation may have an impact on HCV clearance.[22]

Genetic studies showed that genetic variation in the IL28B gene, which

encodes IFN-λ-3 is associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.[8]

Other studies have reported associations of SNPs in IL28B gene with

response to antiviral therapy. Among the most significant SNPs were

rs12979860 and rs12980275.[9-11] In the current study,

the allele frequency at the rs12979860 SNP was 64% for the wild allele

C and 36% for the mutant allele T. The frequency of the wild allele in

this study is similar to that detected in a previous Egyptian study

(67%),[23] in another North African (Moroccan) population (68%)[12] and in some European populations (60-70%),[8] but higher than that found in southern African populations (23-40%) and less than in Asian population (75-98%).[8]

The allele frequency at the rs12980275 SNP was 54% for the wild allele

A and 46% for the mutant allele G. This wild allele frequency is

similar to that among Caucasian population (52%)[13] but less than that detected in previous studies including Saudi population (62%)[24] and European population (62.6%).[25]

Our

results show that IL28B gene polymorphisms are not associated with

spontaneous resolution of HCV in this group of children with SCD.

However, the generalization of these preliminary observations is

limited by the small sample size. The association between SNP

(rs12979860) of the IL28B gene and the outcome of HCV infection was

first described in 2009. Investigators found that the CC genotype of

the rs12979860 SNP was associated with an improved response to

treatment of adult patients with HCV independent of their ethnicities.[9]

Since that, multiple studies have confirmed and reinforced the

association between the C allele of the rs12979860 SNP and both

spontaneous and treatment-induced clearance of HCV in adults.[26]

Fewer

data are available regarding the effect of rs12980275 SNP of IL28B gene

on HCV outcome. A genome-wide association study in 2009 found that the

A allele of the rs12980275 SNP was associated with good response to

treatment in adult Japanese patients with HCV.[11] A subsequent study confirmed the association between rs12980275 SNP and higher response to treatment in adults with HCV.[24]

In

children, data about the relation between polymorphisms in IL28B gene

(rs12979860 and rs12980275) and spontaneous clearance of HCV is

limited. In contrast to our results and in agreement with that already

demonstrated in adults, two studies published in 2011 demonstrated for

the first time that the C allele of rs12979860 SNP of the IL28B is

associated with spontaneous clearan ce of HCV in children.[27,28] These preliminary results have been confirmed in a subsequent study including a larger cohort of Italian children with HCV.[29]

To

our knowledge, no previous study addressed the relation between

rs12980275 SNP of IL28B gene and spontaneous resolution of HCV in

children.

The mechanism behind the association of genetic

variations in the IL28B gene and spontaneous clearance of HCV may be

related to the host innate immune response. IL28B encodes IFN-λ-3,

which is involved in viral control, including HCV.[30]

Both IFN-α and IFN-λ-3 bind to cell-surface receptors leading to

induction of interferon stimulating genes, a mechanism by which IFNs

suppress viral infections.[30-32]

Conclusions

The present study revealed that the prevalence of HCV infection among Egyptian patients with SCD is considerably high. Despite more-effective donor screening methods, blood transfusion still carries a risk of transmission of HCV, especially in multi-transfused patients. Efforts should be made to implement a more sensitive molecular method for screening of blood products for HCV. In the current study, more than half of HCV positive patients show spontaneous viral clearance. Polymorphisms in the IL28B may not be associated with spontaneous clearance of HCV infection among this group of children with SCD. This study is limited by the small number of HCV positive patients. Before generalization of our results, larger studies are required to assess better the impact of genetic variation in IL28B gene on HCV outcome in children.

References

[TOP]