Kunal Tewari1, Vishal Vishnu Tewari2* and Ritu Mehta3.

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care1, Base Hospital, New Delhi.

2 Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics2, Army Hospital (Referral & Research), New Delhi.

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology3, Base Hospital, New Delhi.

Corresponding

author: Dr Vishal Vishnu Tewari, MD (Pediatrics), DNB (Neonatology),

MNAMS, Associate Professor. Department of Pediatrics, Army Hospital

(Referral & Research), New Delhi – 110010. M: +91-8826118889,

+91-7391044489 E-mail:

docvvt_13@hotmail.com

Published: March 1, 2018

Received: January 10, 2018

Accepted: February 5, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018021 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.021

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

Dengue is a major health issue with seasonal rise in dengue fever cases

imposing an additional burden on hospitals, necessitating bolstering of

services in the emergency department, laboratory with creation of

additional dengue fever wards.

Objectives: To study the clinical and hematological profile of dengue fever cases presenting to a hospital.

Methods:

Patients with fever and other signs of dengue with either positive NS1

antigen test or IgM or IgG antibody were included. Age, gender,

clinical presentation, platelet count and hematocrit were noted and

patients classified as dengue fever without warning signs (DF) or with

warning signs (DFWS), and severe dengue (SD) with severe plasma

leakage, severe bleeding or severe organ involvement. Duration of

hospitalization, bleeding manifestations, requirement for platelet

component support and mortality were recorded.

Results:

There were 443 adults and 57 children between 6 months to 77 year age.

NS1 was positive in 115 patients (23%). Fever (99.8%) and severe body

ache (97.4%) were the commonest presentation. DF was seen in 429 (85.8

%), DFWS in 55 (11%), SD with severe bleeding in 10 (2%) and SD with

severe plasma leakage in 6 cases (1.2%). Outpatient department (OPD)

treatment was needed in 412 (82%) and hospitalization in 88 (18%).

Intravenous fluid resuscitation was needed in 16 (3.2%) patients.

Thrombocytopenia was seen in 335 (67%) patients at presentation.

Platelet transfusion was needed in 46 (9.2%). Packed red blood cell

(PRBC) transfusion was given in 3 patients with DFWS and 10 of SD with

severe bleeding. Death occurred in 3 patients of SD with severe plasma

leak and 2 patients with SD and severe bleeding.

Conclusions:

Majority of DF cases can be managed on OPD basis. SD with severe

bleeding or with severe plasma leakage carries high mortality.

Hospitals can analyze annual data for resource allocation for capacity

expansion.

|

Introduction

Dengue is an acute self-limited systemic viral infection caused by the dengue virus belonging to the family flaviviridae.[1]

Incidence of dengue fever (DF) has been increasing from past few years

and dengue has become a global problem in recent times.[2]

Dengue fever with warning signs (DFWS) and severe dengue (SD) with

severe plasma leakage, severe bleeding or severe organ involvement have

emerged as important public health threat in urban areas. This is

attributable to population migration to cities resulting in urban

overcrowding and infrastructure construction in these areas providing

unhindered opportunities for breeding of the vector.[3]

There is a seasonal rise in the number of cases especially during the

months of May to September presenting to the emergency and outpatient

departments which imposes an additional load to an already overburdened

system especially for staffing, laboratory and acute ward admission.

The clinical presentation of DF is triphasic with the febrile phase

typically characterized by high fever, headache, myalgia, body ache,

vomiting, joint pain, transient rash and mild bleeding manifestations

such as petichiae, ecchymosis at pressure sites and bleeding from

venipunctures.[4] In the next critical phase there is

a heightened risk of progression of the patient to severe dengue which

is defined by presence of plasma leakage that may lead to shock and/or

fluid accumulation such as ascites or pleural effusion with or without

respiratory distress, severe bleeding, and/or severe organ impairment.[5]

The risk of severe bleeding in dengue is much higher with a secondary

infection and is seen in about 2-4% of cases having secondary

infection.[6-9] Atypical presentations are also

encountered with acute liver failure, encephalopathy with seizures,

renal dysfunction, lower gastrointestinal bleeding.[10] Several studies have previously analyzed the clinico-epidemiologic profile of dengue infection.[11,12,13]

In this study we evaluated patients with dengue presenting to the

outpatient or emergency departments of a tertiary care hospital in an

urban setting for their clinical and hematological profile, management

and outcomes.

Material and Methods

This

was an observational prospective study conducted at a tertiary care

hospital over a period of 05 months during the dengue fever season

between May 2013 and Sept 2013. Patients presenting to the emergency

department, outpatient department (OPD) or pediatric OPD with

complaints of fever and clinical features of dengue with positive NS1

antigen test or dengue antibody serology IgM or IgG or both were

included in the study. Age, gender, clinical presentation, duration of

fever, dehydration, hemodynamic status, urine output, hepatomegaly,

ascites, pleural effusion, presence of petechiae, positive tourniquet

test, other bleeding manifestations, hematocrit and platelet count were

recorded at presentation. Increased hematocrit was taken as a value

> 45% while thrombocytopenia was defined a platelet count < 1

lac/cu.mm. Patients were categorized as dengue fever without warning

signs (DF), dengue fever with warning signs (DFWS), or severe dengue

(SD) based on presence of abdominal pain, vomiting, pleural effusion,

ascites, lethargy and restlessness, hepatomegaly, severe bleeding,

respiratory distress, and other organ involvement as per the World

Health Organization (WHO) classification.[5] Diagnosis

of dengue was made on the basis of NS1 antigen positivity and/or

detection of IgM and IgG antibodies using a commercially available

one-step immunochromatographic assay (SD Bioline Dengue Duo, Alere,

Germany). NS1 antigen test was done in all patients with clinical

features suggestive of dengue infection presenting within 5 days of

onset of the symptoms. In patients with clinical features suggestive of

dengue infection who presented beyond 5 days of onset of symptoms IgM

and IgG antibody test was done. All patients with bleeding

manifestations, thrombocytopenia with platelet count < 30,000 cu/mm

were admitted. All pregnant patients and infants irrespective of their

platelet counts were admitted. The mainstay of therapy was maintenance

of hydration status and early recognition of plasma leakage and shock.

Management of cases was done strictly as per the guidelines for

clinical management of dengue.[5] Paracetamol was

given for fever and pain relief with complete avoidance of any other

non-steroidal analgesic (NSAID). Patients were treated with oral

rehydration therapy, intravenous (IV) fluid therapy, packed red blood

cell (PRBC) transfusion, platelet concentrates depending upon the

clinical condition. Patients with DF were managed with oral rehydration

salt (ORS) solution, oral paracetamol and advised review every 3 days.

Patients with warning signs including a rising hematocrit (>20%

increase over baseline) and falling platelet count were managed with

0.9% Normal Saline (NS) infusion started at 5-7 ml/kg/hour for 1-2

hours, 3-5 ml/kg/hour for the next 2-4 hours and finally 2-3 ml/kg/hour

maintaining the urine output at 0.5-1 ml/kg/hour and monitoring the

hematocrit for rise. In spite of this if the hematocrit continued to

show a rising trend, a NS bolus of 10 ml/kg was given followed by

another round of NS infusion as described. IV fluids were continued

till patients clinical condition was stable and oral intake adequate.

Patients with SD with severe plasma leakage or severe bleeding were

given fluid resuscitation with IV NS bolus of 20 ml/kg over 1-2 hours,

repeated under close supervision. The intake-output charting was done

meticulously realizing fully that the input to output ratio was not

adequate for judging fluid requirement during this period. Fluid

resuscitation was considered adequate with decreasing tachycardia,

improving blood pressure, pulse volume, warm extremities, capillary

refill time (CRT) < 2 seconds, urine output ≥ 0.5 ml/kg/hour,

decreasing metabolic acidosis and normal sensorium. Patients were

discharged once there were no signs of dehydration, adequate urine

output and platelet count > 50,000 cu/mm. Oxygen therapy by face

mask was given wherever it was necessary. PRBC transfusion was given in

patients with clinical bleeding with significant blood loss (6-8 ml/kg)

or evidence of hemolysis. Institutional ethical committee clearance was

obtained and written informed consent was taken from all patients.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described as proportions.

Data was analyzed using SPSS 17.

Results

There

were 443 adult patients and 57 children who were diagnosed to have the

various dengue syndromes over the 5 month period of observation. Of the

443 adult patients, 223 were males and 220 were females. Amongst the

females 4 patients were pregnant. There were 36 boys and 21 girls in

the pediatric population. Patients’ age varied from 6 months to 77

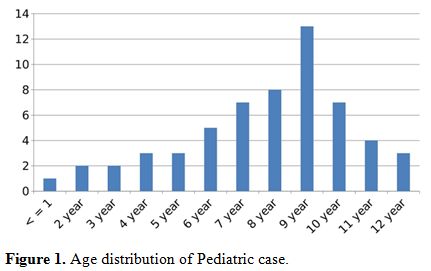

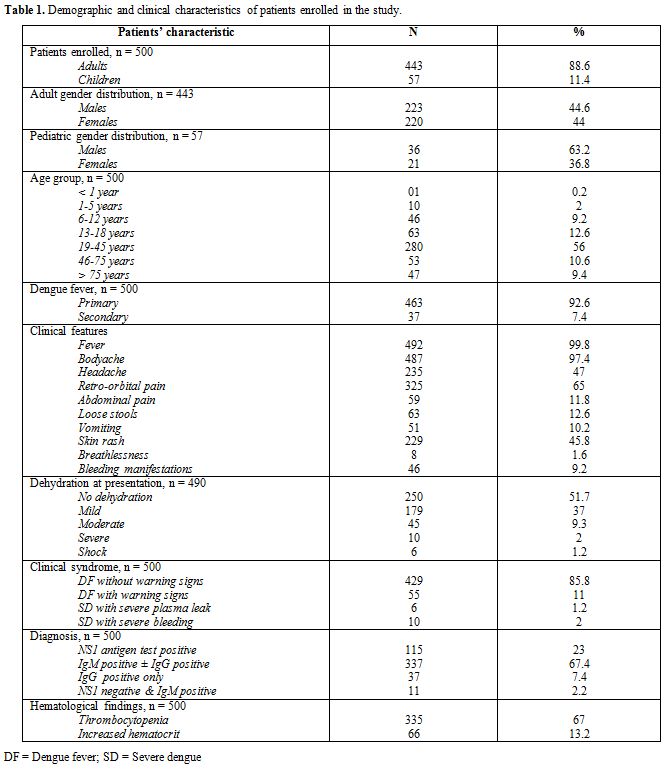

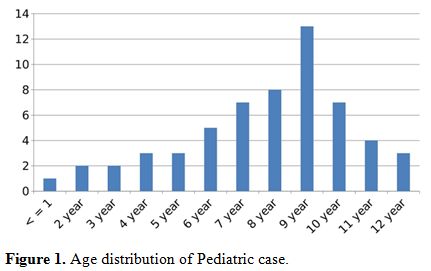

years. Age wise distribution of children with DF is as shown (Figure 1). NS1 was positive in 115 patients (115/500; 23%), IgM antibody test was positive in 337

|

Figure 1. Age distribution of Pediatric case. |

patients (337/500;

67.4%) while in 37 patients (37/500; 7.4%) the IgM antibody was

negative but they showed positivity for IgG antibody. In 11 patients

(11/500; 2.2%) initial sample was negative for NS1 antigen test but IgM

antibody test done two to five days later was positive. The commonest

presenting complaint was fever (99.8%) with

severe arthralgia and myalgia (97.4%). Other symptoms

were loose motions (12.6%), rashes (45.8%), vomiting (10.2%),

breathlessness (1.6%), headache (47%), retro-orbital pain (65%) and

abdominal pain (11.8%). Breathlessness was seen in 8 patients (1.6%)

all of whom had serositis. DF was diagnosed in 429 cases (429/500; 85.8

%), DFWS in 55 cases (55/500; 11%), SD with severe bleeding in 10

(10/500; 2%) and SD with severe plasma leakage in 6 cases (6/500; 1.2%)

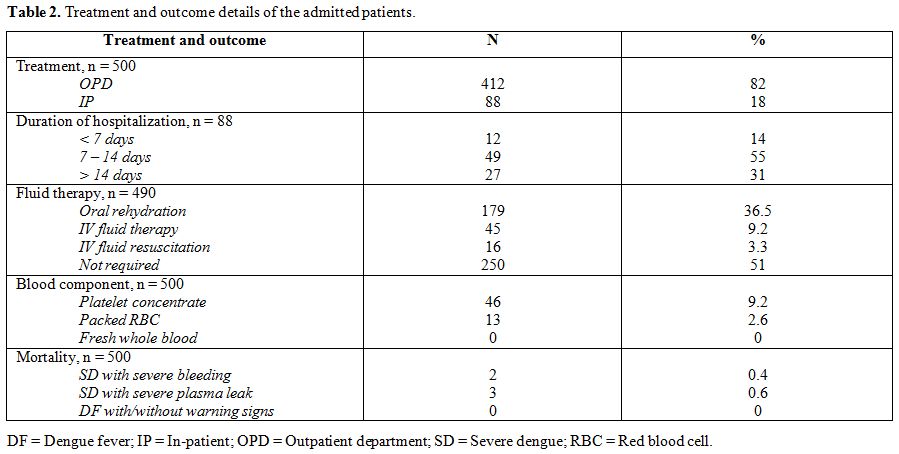

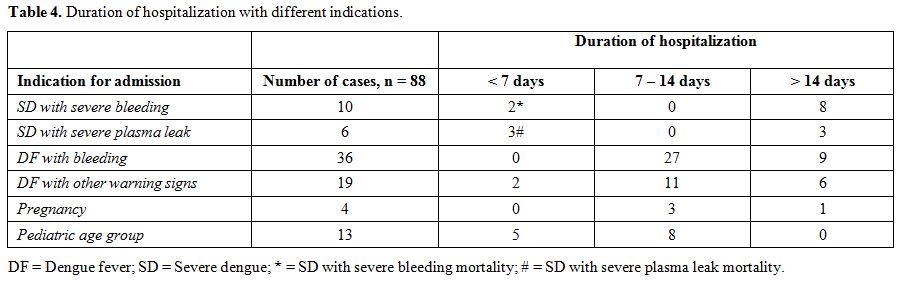

(Table 1). Four hundred and

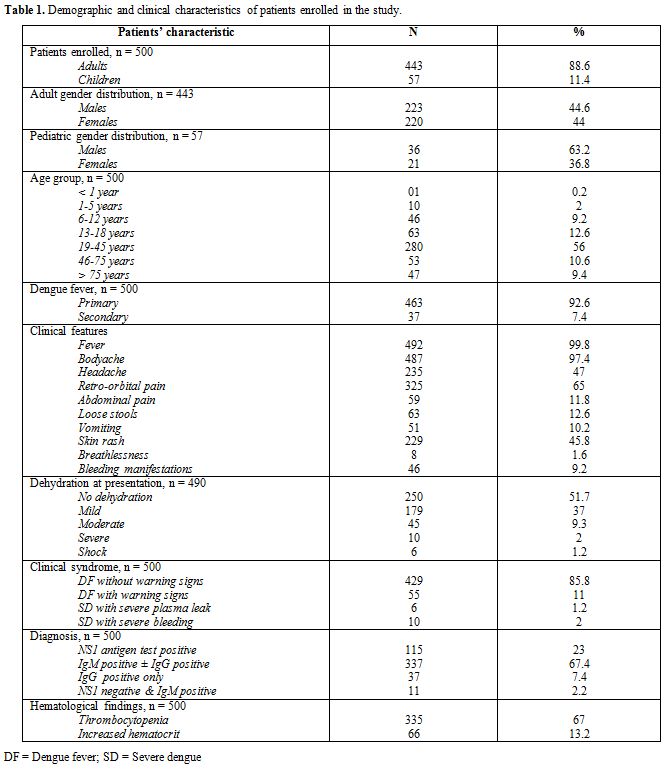

twelve cases (412/500; 82%) were treated as outpatients while 88

patients (88/500; 18%) required admission. All 55 cases of DFWS, 10

patients of SD with severe bleeding, 6 patients of SD with severe

plasma leak, all 4 pregnant patients and 13 children were hospitalized.

Mild dehydration was noted in 179 patients of DF (179/484; 36.9%) who

were treated with oral rehydration therapy, while 45 cases of DFWS

(45/484; 9.3%) required intravenous fluid therapy. Sixteen patients

(16/490; 3.2%) had severe dehydration requiring IV fluid resuscitation

of which 10 cases were of DFWS and 6 were of SD with severe plasma leak

(Table 2). Thrombocytopenia was

seen in 335 (335/500; 67%) patients while increased hematocrit was seen

in 66 (66/500; 13.2%) patients at the time of presentation (Table 1).

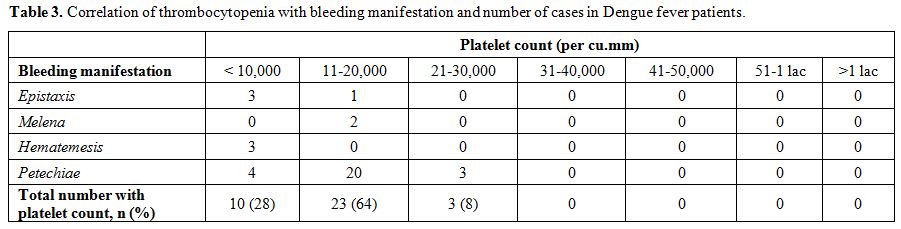

Bleeding manifestations were seen in 36 patients of DFWS (36/55;

65.4%). Out of these 27 patients had petechiae, 4 patients had

epistaxis, 3 had hematemesis and 2 had melena. Amongst these, 10

patients had platelet count < 10,000/cu.mm, 23 patients had platelet

count was between 11-20,000/cu.mm while in 3 patients the platelet

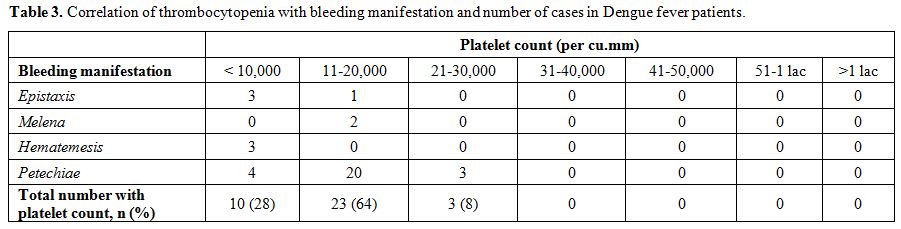

count was between 21-30,000/cu.mm (Table 3).

Platelet transfusions were given in all 36 cases. PRBC transfusion was

required in 3 patients with DFWS with hemoglobin < 8.5 gm/dl and 10

patients with SD with severe bleeding. All 10 patients with SD with

severe bleeding required platelet transfusions. Three patients of SD

with severe plasma leak and 2 patients of SD with severe bleeding died.

There was no mortality in the pediatric cases or the pregnant women.

|

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in the study. |

|

Table 2.

Treatment and outcome details of the admitted patients. |

|

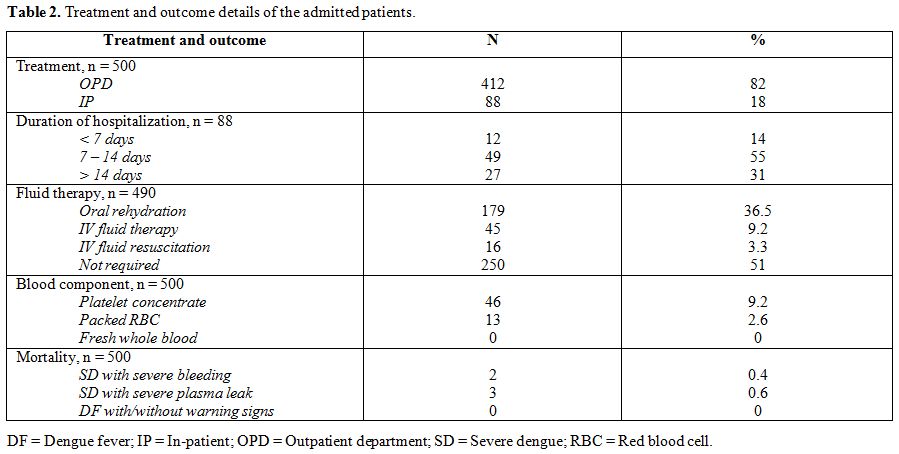

Table 3. Correlation of thrombocytopenia with bleeding manifestation and number of cases in Dengue fever patients. |

|

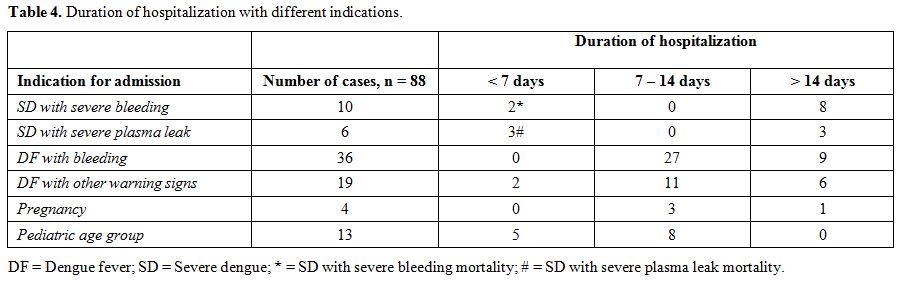

Table 4. Duration of hospitalization with different indications. |

Discussion

Our

institute located in South-West Delhi where this study was carried out

serves as the nodal center for management of dengue fever for the

clientele we serve. Our study aimed at a descriptive

clinico-hematologic profile of the dengue morbidity during the seasonal

spike. We evaluated 500 cases of serologically confirmed dengue cases

over 5 months, of which 88 required admission using strict admission

criteria (88/500; 18%). The age spectrum was wide including infants,

children, pregnant women, young adults and elderly. Young children of

school going age were particularly susceptible within the pediatric age

group (Figure 1). The commonest

clinical presentation was severe arthralgia, myalgia, headache and

retro-orbital pain. In children high fever with vomiting, pain abdomen

and an erythematous macular rash was the commonest clinical

presentation. High fever in infants and young children (below 5 years)

predisposes them to febrile seizures and was vigorously addressed.

Majority of the patients who required hospitalization had warning signs

at presentation (55 cases of DFWS and 2 cases of SD with severe

bleeding) (57/88; 62.5%). Tachypnea at presentation was associated with

serositis in all cases (8/500; 1.6%) and served as a simple sign

prompting admission. Majority of patients with some dehydration could

be managed with oral rehydration. About 9% cases required intravenous

fluid therapy and only 3% who progressed to SD with severe plasma leak

or severe bleeding required aggressive IV fluid resuscitation.

Thrombocytopenia was seen in the majority applying the standard

definition (335/500; 67%). However, platelet transfusion was required

in only 36 patients of DFWS and 10 cases of SD. The average requirement

of platelet concentrate for DFWS patients was 3 while for SD patients

was 12. None of the patients with platelet count > 30,000/ cu. mm

received platelet transfusions. Patients required hospitalization for a

period of 7-14 days due to DFWS with clinical bleeding and other

warning signs (55/88; 62.5%). Only cases with SD with severe bleeding

or severe plasma leakage required hospitalization for > 14

days.

Appropriate timing of NS1 antigen test is important.

We performed NS1 antigen testing in patients presenting within 5 days

of onset of symptoms in order to reliably identify cases of primary

dengue infection as well as secondary dengue infection also in which

the NS1 antigen test remains positive for a shorter time frame.[14]

There were 11 (2.2%) patients in whom the NS1 antigen test turned out

to be negative but were later confirmed to be dengue IgM antibody test

positive. We used the one-step immunochromatographic assay for IgM and

IgG antibody testing which identifies acute as well as past dengue

infections with excellent sensitivity and specificity.[15]

There were 37 (7.4%) patients in whom the IgM antibody was negative but

IgG antibody was positive. These patients were cases of secondary

dengue infection which were confirmed by a ≥ 4 fold elevation in the

IgG antibody titres by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (IgG-ELISA) in

the convalescent serum sample at follow-up done at a reference

laboratory. Out of these 37 patients, 4 had DFWS requiring

hospitalization but none had SD. The 11 (2.2%) patients in whom the NS1

antigen test was negative were cases of acute infection confirmed by

IgM antibody testing who presented more than five days since onset of

fever which explains the initial negative NS1 antigen test.

The

use of NS1 antigen test, IgM and IgG antibody testing for diagnosis of

dengue infection can show false positivity due to cross reaction with

other flaviviral infections.[16] We did not use

real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for viral RNA detection

for diagnosis due to feasibility issues and these are the limitations

of our study. The strength of this study is the inclusion of

serologically confirmed cases, inclusion of patients of all age groups

and threadbare clinical and hematological profile of the enrolled

cases, which can help guide local health authorities on resource

allocation for capacity expansion. This is a single center experience

and since our hospital serves a specific clientele (armed forces

personnel, in active service or retired and their dependents), this is

a limitation of this study. However this should not affect its external

validity and the generalizability of its findings.

Several outbreaks of DF have been reported over the past 2 decades[17-23] and a seasonal trend during the monsoon period has been noted[24] due to the warm environment and high relative humidity[25] favoring vector growth. The reported case fatality rate shows a declining trend[26] from 6-9%[17,18,27] to 0%[23] attributable to increased awareness and better case diagnosis and management.[5] There has been increasing atypical and rare presentations of DF resulting in the expanded dengue definition.[28,29]

Some studies similar to ours from other parts of the country have

reported significant differences in the incidence of atypical

presentation like neurological signs or the incidence of serositis[11,12] while others have reported similar findings.[23] These differences may be due to co-infection with other pathogens[28] or secondary heterotypic dengue virus infections.[30] Dengue is grossly underreported in our country.[31]

The WHO estimates that nearly 5 lac people are admitted with dengue in

our country annually and that India accounts for nearly 20% of all

cases in the south-east Asian region (SEAR).[32]

Conclusions

We

have presented the profile of dengue cases seen during the seasonal

surge of cases handled in the emergency, OPD and laboratory of a

hospital serving as a nodal hospital for management of DF in South-West

Delhi. Our findings show that majority of DF cases can be managed on

OPD basis, NS1 antigen test maybe false negative if done too early in

the course of the illness, patients with DFWS require admission of up

to 7-14 days, thrombocytopenia is common but very few patients will

require platelet transfusion and the average requirement of platelet

concentrates in DFWS and SD is 3 and 12. SD with plasma leak and

bleeding carry high mortality.

Acknowledgements

The

authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the patients and the

staff in the Accident and Emergency Department Base Hospital and

Pediatric OPD of Army Hospital (Referral and Research) Delhi.

.

References

- Gubler DJ. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Arch Med Res 2002; 33(4): 330-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0188-4409(02)00378-8

- Bhatt

S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The

global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013; 496:504-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12060 PMid:23563266 PMCid:PMC3651993

- Chaudhuri M. What can India do about dengue fever? BMJ 2013; 346: f643. doi:10.1136/bmj.f643 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f643

- Simmons CP, Farrar JJ, Chau NV, Wills B. Dengue. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1423-32. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1110265 PMid:22494122

- World Health Organization. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547871eng.pdf [accessed 15 Nov 2017]

- Amin

P, Acicbe O, Hidalgo J, Jimenez JIS, Baker T, Richards GA. Dengue

fever: report from the task force on tropical diseases by the world

federation of societies of intensive and critical care medicine. J Crit

Care 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.11.003

- Guzman MG, Kouri G. Dengue: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2(1): 33-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00171-2

- Kouri

GP, Guzman MG, Bravo JR. Why dengue haemorrhagic fever in Cuba? 2: an

integral analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1987; 81: 821–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(87)90042-3

- Basheer

A., Iqbal N., Mookkappan S., Anitha P., Nair S., Kanungo R., Kandasamy

R. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of dengue-orientia

tsutsugamushi co-infection from a tertiary care center in south india.

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016028 https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2016.028

- Gupta

N, Srivastava S, Jain A, Chaturvedi UC. Dengue in India. Indian J Med

Res 2012; 136: 373-90. PMid:23041731 PMCid:PMC3510884

- Karoli

R, Fatima J, Siddiqi Z, Kazmi KI, Sultania AR. Clinical profile of

dengue infection at a teaching hospital in North India. J Infect Dev

Ctries 2012; 6(7):551-54. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.2010 PMid:22842941

- Mandal

SK, Ganguly J, Sil K, Chatterjee S, Chatterjee K, Sarkar P, et al.

Clinical profiles of dengue fever in a teaching hospital of eastern

India. Nat J Med Res 2013; 3(2) 173-76.

- Roy

MP, Gupta R, Chopra N, Meena SK, Aggarwal KC. Seasonal Variation and

Dengue Burden in Paediatric Patients in New Delhi. J Trop Pediatr 2017.

https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmx077

- Pal

S, Dauner AL, Mitra I, Forshey BM, Garcia P, Morrison AC, et al.

Evaluation of Dengue NS1 Antigen Rapid Tests and ELISA Kits Using

Clinical Samples. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(11): e113411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113411

- Wang

SM, Sekaran SD. Early diagnosis of dengue infection using a commercial

dengue duo rapid test kit for the detection of NS1, IGM and IGG. Am J

Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83(3):690-5. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0117 PMid:20810840 PMCid:PMC2929071

- Zammarchi

L., Spinicci M., Bartoloni A. Zika virus: a review from the virus

basics to proposed management strategies. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis

2016; 8(1): e2016056, doi: https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2016.056

- Anuradha

S, Singh NP, Rizvi SN, Agarwal SK, Gur R, Mathur MD. The 1996 outbreak

of dengue hemorrhagic fever in Delhi, India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med

Public Health 1998; 29(3): 503-6. PMid:10437946

- Kabra

SK, Jain Y, Pandey RM, Madhulika, Singhal T, Tripathi P, et al. Dengue

haemorrhagic fever in children in the 1996 Delhi epidemic. Trans R Soc

Trop Med Hyg 1999; 93(3): 294-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90027-5

- Singh

NP, Jhamb R, Agarwal SK, Gaiha M, Dewan R, Daga MK, et al. The 2003

outbreak of Dengue fever in Delhi, India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med

Public Health 2005; 36(5): 1174-8. PMid:16438142

- Bharaj

P, Chahar HS, Pandey A, Diddi K, Dar L, Guleria R, et al. Concurrent

infections by all four dengue virus serotypes during an outbreak of

dengue in 2006 in Delhi, India. Virol J 2008; 5:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-5-1

- Jhamb

R, Kumar A, Ranga GS, Rathi N. Unusual manifestations in dengue

outbreak 2009, Delhi, India. J Commun Dis 2010; 42(4): 255-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1201-9712(10)60301-3

- Jain

S, Sharma SK. Challenges & options in dengue prevention &

control: A perspective from the 2015 outbreak. Indian J Med Res 2017;

145: 718-21. PMid:29067972 PMCid:PMC5674540

- Laul

A, Laul P, Merugumala V, Pathak R, Miglani U, Saxena P. Clinical

Profiles of Dengue Infection during an Outbreak in Northern India. J

Trop Med 2016; Article ID 5917934. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5917934

- Dar

L, Broor S, Sengupta S, Xess I, Seth P. The First Major Outbreak of

Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever in Delhi, India. Emerg Inf Dis 1999; 5(4):

589-90. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0504.990427 PMid:10458971 PMCid:PMC2627747

- Roy

MP, Gupta R, Chopra N, Meena SK, Aggarwal KC. Seasonal Variation and

Dengue Burden in Paediatric Patients in New Delhi. J Trop Pediatr 2017;

https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmx077

- Chakravarti A, Arora R, Luxemburger C. Fifty years of dengue in India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012; 106:273-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.12.007 PMid:22357401

- Aggarwal

A, Chandra J, Aneja S, Patwari AK, Dutta AK. An epidemic of dengue

hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome in children in Delhi.

Indian Pediatr 1998; 35(8):727-32. PMid:10216566

- Kadam DB, Salvi S, Chandanwale A. Expanded dengue. J Assoc Physicians India 2016; 64(7):59-63. PMid:27759344

- Tansir

G, Gupta C, Mehta S, Kumar P, Soneja M, Biswas A. Expanded dengue

syndrome in secondary dengue infection: A case of biopsy proven

rhabdomyolysis induced acute kidney injury with intracranial and

intraorbital bleeds. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2017; 6(4):314-18. https://doi.org/10.5582/irdr.2017.01071 PMid:29259863 PMCid:PMC5735288

- Halstead SB. Dengue. Lancet 2007; 370:1644–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0

- Kakkar

M. Dengue fever is massively under-reported in India, hampering our

response. BMJ 2012; 345:e8574. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8574. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8574

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2013. Dengue and severe dengue: Fact sheet No. 117. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/, [accessed on 15 Nov 2017].

[TOP]