Roberto Antonucci1, Nadia Vacca1, Giulia Boz1, Cristian Locci1, Rosanna Mannazzu1, Claudio Cherchi2, Giacomo Lai1 and Claudio Fozza3.

1 Pediatric Clinic, Department of Medical, Surgical and Experimental Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy.

2 Respiratory Unit, Academic Department of Pediatrics, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

3 Hematology, Department of Medical, Surgical and Experimental Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy.

Corresponding

author: Prof. Roberto Antonucci, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatrics.

Pediatric Clinic, Department of Medical, Surgical and Experimental

Sciences, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy. Tel. +39 079 228239.

E-mail:

rantonucci@uniss.it

Published: May 1, 2018

Received: February 21, 2018

Accepted: April 19, 2018

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018, 10(1): e2018034 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2018.034

This article is available on PDF format at:

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Severe

hypereosinophilia (HE) in children is rare, and its etiological

diagnosis is challenging. We describe a case of a 30-month-old boy,

living in a rural area, who was admitted to our Clinic with a 7-day

history of fever and severe hypereosinophilia. A comprehensive

diagnostic workup could not identify the cause of this condition. On

day 6, the rapidly increasing eosinophil count (maximum value of

56,000/mm3), the risk of developing

hypereosinophilic syndrome, and the patient’s history prompted us to

undertake an empiric treatment with albendazole. The eosinophil count

progressively decreased following treatment. On day 13, clinical

condition and hematological data were satisfactory, therefore the

treatment was discontinued, and the patient was discharged. Three

months later, anti-nematode IgG antibodies were detected in patient

serum, thus establishing the etiological diagnosis. In conclusion, an

empiric anthelmintic treatment seems to be justified when parasitic

hypereosinophilia is strongly suspected, and other causes have been

excluded.

|

Introduction

Hypereosinophilia (HE) is defined as an eosinophil count in peripheral blood >1,500/mm3. The World Health Organisation categorizes eosinophilia into mild (600-1,500/mm3), moderate (1,500-5,000/mm3), and severe (>5,000/mm3). An increased number of eosinophils can be potentially associated with organ damage.[1]

HE can be distinguished into primary, secondary, familial and

idiopathic. The primary form is a clonal disease classified in the

context of hematologic malignancies.[2] Secondary (or

reactive) HE is caused by underlying conditions, such as parasitosis,

allergic or autoimmune diseases, or drug reactions, and results from a

non-clonal increase in blood eosinophil levels, often driven by the

overproduction of IL-5.[3] Hereditary (familial) HE

(HEFA) is a rare autosomal dominant condition, characterized by HE

associated with end-organ damage. Idiopathic hypereosinophilia (or

hypereosinophilia of undetermined significance) (HEUS) is a diagnosis

of exclusion which can be considered when all causes of a reactive HE

have been ruled out. Rarely, a severe HE can be associated with organ

damage or dysfunction, in the context of the so-called

hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). In such cases, the tissue

infiltration by eosinophils can result in cell damage, due to the

release of eosinophil granule contents, thus leading to significant

morbidity.[4] Severe hypereosinophilia (HE) is a rare

condition in children. The etiological diagnosis of this condition is

often challenging, with a possible delay in treatment.

Case Report

We

describe a case of a 30-month-old boy who was admitted to the Pediatric

Clinic, University of Sassari, Italy, with a 7-day history of fever.

Two weeks before hospitalization, the patient had had a transient

episode of diarrhea. Just before admission, laboratory tests revealed a

raised white blood cell (WBC) count of 49,920/mm3 with an eosinophil count of 26,310/mm3,

mild microcytic anemia (11.1 g/dL) and high serum total IgE levels (968

UI/mL). The child lived in a rural area of the Mediterranean island of

Sardinia, in close contact with animals, and had never experienced any

medical problem. Moreover, the history revealed that the patient was

not atopic, had been regularly vaccinated, and had not received any

pharmacological treatment before hospital admission. Moreover, he had

no history of recent travels.

On admission, the patient was

apparently well, afebrile, with no other clinical manifestations. At

physical examination, there was no evidence of hepato-splenomegaly and

lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests showed an increase in both WBC count

(WBC, 58,020/mm3), and eosinophil count (eosinophils, 33,400/mm3;

57.5%); in addition, a moderate elevation of CRP levels (2.85 mg/dL)

was found, while serum electrolytes, hepatic and renal markers were

normal. Anamnestic, clinical and laboratory findings were considered

suggestive for neoplastic or parasitic etiology. In order to exclude a

neoplastic HE, a peripheral blood smear and a bone marrow aspirate were

performed. The former was normal except for the raised eosinophil

percentage, while the bone marrow smear showed an expansion of the

eosinophilic lineage (90%) in the absence of blasts. RT-PCR excluded

the presence of leukemia-associated genetic abnormalities, and

lymphocyte subpopulations, when analyzed by flow cytometry, were

normal. In order to exclude a parasitic etiology, the major types of

helminths and protozoa responsible for infections associated with

hypereosinophilia were investigated by examination of fresh stool,

“scotch tape test” (specific for Enterobius Vermicularis),

examination of urine, and serologic testing (Echinococcus, Toxocara

canis, Cysticercus and Trichinella sp.). All tests were negative for

parasitic infection. Chest X-Ray, Doppler echocardiography, abdominal

and pelvic ultrasound as well as an eye examination excluded thoracic,

abdominal or pelvic lesions and eosinophilic organ infiltration.

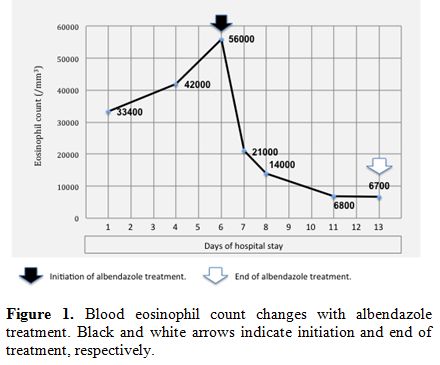

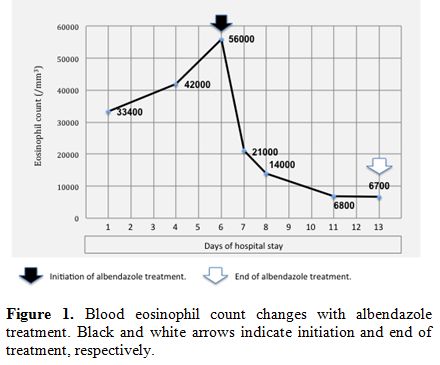

During hospitalization, blood eosinophil count further increased, reaching the maximum value of 56,000/mm3

after six days. Under suspicion of parasitic etiology, mainly driven by

the patient's living conditions, and to prevent possible organ damage

due to eosinophil infiltration, empiric treatment with albendazole (15

mg/kg/day) was started. After only 24 hours, the eosinophil count was

21,000/mm3 and continued to decrease in the following days (Figure 1). On day 13, blood eosinophils were 6,700/mm3,

the clinical condition was satisfactory, and therefore the treatment

was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home. The eosinophil

count was found to be within the normal range one month after the end

of therapy.

|

Figure 1. Blood eosinophil count changes

with albendazole treatment. Black and white arrows indicate initiation

and end of treatment, respectively. |

At three months

after discharge, IgG anti-nematode antibodies were detected in serum

samples from the patient and his father by ELISA test (using raw

antigen), which was performed by the Italian Higher Institute of Health.

Discussion

Hypereosinophilia

can be associated with many infectious, neoplastic, immunological and

genetic diseases, or to drug reactions. Therefore, a careful family and

personal history is mandatory to investigate conditions related to

eosinophilia, such as atopy, medications, diet, travels and

environmental exposure to parasites.[5] In this case,

the specific living environment of the child, a country farm with close

contact with animals, played a central role in generating our

diagnostic hypothesis. In details, an atopic condition was excluded

based on the dramatic increase in eosinophils and the history of fever.

On the other hand, a neoplastic etiology was ruled out by performing

peripheral and medullary smears, RT-PCR and lymphocyte subpopulations

studies. Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA), a rare

systemic necrotizing vasculitis, was also taken into consideration in

the differential diagnosis, but it was ruled out because of the age of

the patient, the absence of history of atopy, asthma or rhinitis, as

well as the lack of signs of vasculitis and extra-vascular granulomas.

Finally,

a parasitic etiology, which was supported by the patient's history,

remained the most likely option. In this regard, it is known that the

specific diagnostic characterization of a parasitic intestinal

infection is difficult. A wide variety of parasites can elicit

eosinophilia,[6] even if only relatively few of them can be responsible for such a marked increase in eosinophil levels.[7]

The pattern and degree of eosinophilia in parasitic infections result

from the development, migration, and distribution of the parasite

within the host, as well as from the host's immune response. Parasites

tend to elicit marked eosinophilia when they or their products come

into contact with immune effector cells in tissues, particularly during

migration. When mechanical barriers separate the parasite from the

host, or when parasites no longer invade tissues, the stimulus to

eosinophilia is usually absent. Therefore, eosinophilia is highest in

infections with a phase of parasite development that involves migration

through tissues (eg, trichinosis, ascariasis, gnathostomiasis,

strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis, and filariasis).[8]

Detection of eggs, larvae or adult worms in feces is necessary to make

a diagnosis. However, being very difficult to obtain, a negative

examination does not allow to exclude a parasitic infection with

certainty. The rapid increase in eosinophil count, the potential risk

of evolution to the hypereosinophilic syndrome or to organ damage,[9]

and the history suggestive of a parasite infection prompted us to

undertake an albendazole-based empiric therapy. Albendazole is a safe

medication, and its use is promoted by WHO to control the infection in

high endemic areas, even when an exact diagnosis is lacking.[10]

Also, empiric albendazole therapy is recommended by the British

Infection Society in returning travelers and migrants from the tropics

to cover the possibility of geohelminth infection as the cause of

transient eosinophilia with negative stool microscopy.[11]

In our case, the treatment was readily effective, leading to a steep

decrease in the eosinophil count in just 24 hours. Therefore, the

diagnosis of parasitic hypereosinophilia was challenging and required

an ‘ex-iuvantibus’ approach, while the diagnosis of nematode infection

was established by serologic testing only three months later.

The

picture of extreme hypereosinophilia is rare in childhood. The

etiological diagnosis of this condition is often challenging for the

clinician, and this may lead to difficulties in deciding upon the

specific choice of treatment for individual patients. The case

described here can be considered emblematic of this hematological

condition and offers the example of a diagnostic-therapeutic approach

that might be applicable in similar contexts. Based on this case report

and the literature data, we can conclude that an empiric anthelmintic

treatment is justified and potentially decisive when hypereosinophilia

of parasitic origin is strongly suspected. References

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny H-P, Roufosse F, Gotlib

J, Weller PF, Hellmann A, Metzgeroth G, Leiferman KM, Arock M,

Butterfield JH, Sperr WR, Sotlar K, Vandenberghe P, Haferlach T, Simon

H-U, Reiter A, Gleich GJ. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria

and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J

Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:607-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Bain

BJ, Fletcher SH. Chronic eosinophilic leukemias and the

myeloproliferative variant of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Immunol

Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:377-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2007.06.001

- Ackerman

SJ, Bochner BS. Mechanisms of eosinophilia in the pathogenesis of

hypereosinophilic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am.

2007;27:357-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2007.07.004

- Crane

MM, Chang CM, Kobayashi MG, Weller PF. Incidence of myeloproliferative

hypereosinophilic syndrome in the United States and an estimate of all

hypereosinophilic syndrome incidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2010;126:179-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.035

- Curtis

C, Ogbogu PU. Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis of Persistent

Marked Eosinophilia. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35:387-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2015.04.001

- Weller PF. Eosinophilia in travelers. Med Clin North Am. 1992;76:1413-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30294-2

- Nutman

TB. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of marked, persistent

eosinophilia. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:529-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2007.07.008

- Moore TA, Nutman TB. Eosinophilia in the returning traveler. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998;12:503-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70016-7

- Roufosse F, Weller PF. Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:39-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.011

- Crompton

DWT. Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: coordinated use of

anthelminthic drugs in control interventions: a manual for health

professionals and programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization

2006 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43545/1/9241547103_eng.pdf

- Checkley

AM, Chiodini PL, Dockrell DH, Bates I, Thwaites GE, Booth HL, Brown M,

Wright SG, Grant AD, Mabey DC, Whitty CJM, Sanderson F, British

Infection Society and Hospital for Tropical Diseases. Eosinophilia in

returning travellers and migrants from the tropics: UK recommendations

for investigation and initial management. J Infect. 2010; 60:1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2009.11.003