Subsequent to the clinical validation of ibrutinib, second-generation BTKis, including acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, were developed and evaluated.[5-6] These next-generation agents exhibit advantageous properties, notably improved safety profiles, and, in the case of zanubrutinib, superior efficacy relative to ibrutinib in specific contexts.[7-8] Consequently, these inhibitors have become integral to the therapeutic armamentarium for a substantial proportion of CLL patients requiring continuous pharmacological intervention [9-10].

Covalent BTKis, including both first- and second-generation agents, exert their therapeutic effect through irreversible binding to the cysteine residue at position 481 (C481) of the BTK protein.[11-12] The development of resistance — most notably via the C481S point mutation — compromises this mechanism by preventing effective drug binding.[12] In addition, activating mutations in Phospholipase C Gamma 2 (PLCG2), a key downstream effector in the B-cell receptor signaling pathway, have been identified as contributors to resistance. These mutations frequently co-occur with BTK mutations, indicating a multifactorial basis for therapeutic failure.[13] Given that second-generation BTKis, such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, rely on the same C481-binding mechanism, the presence of the C481S mutation similarly compromises their efficacy.[12] These findings underscore the ongoing clinical challenge of overcoming acquired resistance to BTKis in the treatment of CLL.

BTK C481S Mutation in Patients Treated with Covalent BTKi

Long-term investigations have demonstrated that mutations in BTK and PLCG2 occur infrequently among patients with CLL undergoing first-line treatment with covalent BTKis.[14-15] This finding is supported by a large retrospective cohort study presented at the 2024 American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting, which included 13,940 CLL patients treated with BTKis for more than one year. BTK mutations were identified in only 1.7% of the cohort, primarily among those who received either ibrutinib or acalabrutinib as first-line therapy. Importantly, these mutations were frequently accompanied by TP53 aberrations, observed in 44.5% of cases. However, the study did not establish a definitive correlation between the co-occurrence of these genetic alterations and resistance to BTKi therapy.[15]Consistent with these findings, a pooled analysis of 238 previously untreated CLL patients from four clinical trials (PCYC-1122e, RESONATE-2, RESONATE-17, and ILLUMINATE) revealed a low incidence of resistance-associated mutations. BTK and PLCG2 mutations were detected in 3% and 2% of patients, respectively, with only 1% harboring both mutations at the last follow-up.[14] Notably, the presence of these mutations was not associated with clinical progression. These data suggest that, in the absence of overt disease progression, the detection of BTK or PLCG2 mutations may not warrant immediate therapeutic intervention or modification.[14]

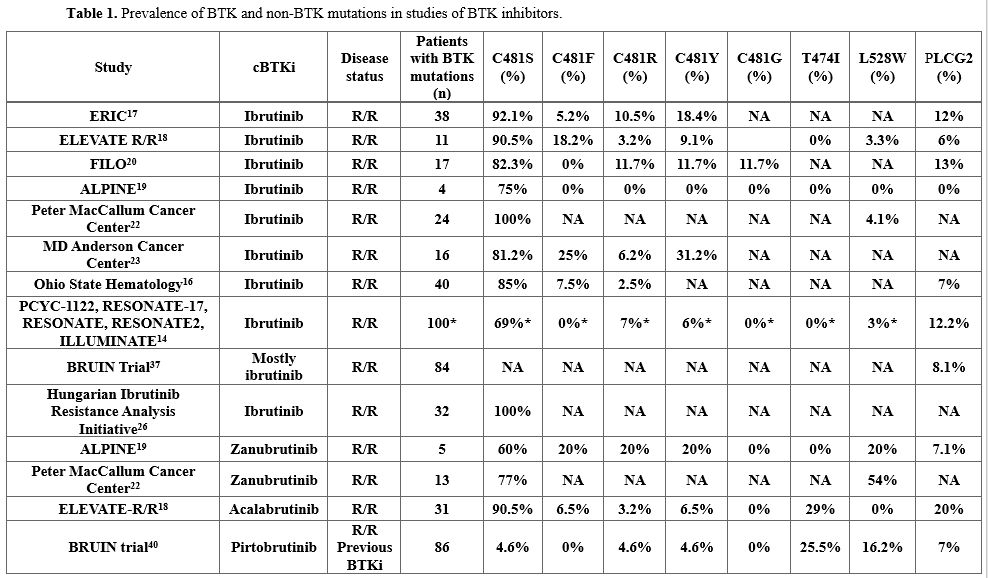

In contrast, acquired BTK C481S mutations are more frequently observed in patients who develop resistance to BTKis[11,16-23] (Table 1). This trend is particularly evident in two recent phase III clinical trials comparing first- and second-generation BTKis in patients with R/R CLL.[17-18]

In the ELEVATE R/R trial, which evaluated acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in previously treated CLL, emergent BTK mutations at the time of disease progression were identified in 66% of patients receiving acalabrutinib and 37% of those treated with ibrutinib. The median variant allele fraction (VAF) of these mutations was 16.1% and 15.6%, respectively.[17]

Similarly, the ALPINE trial, which compared zanubrutinib with ibrutinib in the R/R CLL setting, assessed paired baseline and progression samples from 52 patients. While no BTK mutations were detected at baseline, 15.3% of patients (zanubrutinib, n = 5; ibrutinib, n = 3) acquired a total of 17 BTK mutations upon progression. Notably, 82.4% of these mutations occurred at the C481 residue (zanubrutinib, n = 4; ibrutinib, n = 3).[18]

These clinical trials highlight differences in the incidence of acquired BTK mutations, which may reflect underlying variations in patient characteristics and follow-up duration.[17-18] The higher mutation rate observed in the ELEVATE R/R cohort — enriched for patients with adverse cytogenetic profiles, including del(17p) and del(11q) — suggests a potential link between genomic instability and an increased likelihood of developing resistance mutations.[17]

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the prevalence of BTK and PLCG2 mutations in patients with CLL who experienced progressive disease (PD) while receiving covalent BTKi therapy.[24] The analysis included 724 patients, 92.1% of whom had confirmed PD. BTK mutations were identified in 52% of cases (95% confidence interval [CI]: 39–64%), with similar rates observed in patients treated with first-generation (53%) and second-generation (51%) BTKis.

Among 620 patients assessed for PLCG2 mutations, the prevalence was 11% (95% CI: 7–17%). Importantly, the occurrence of PLCG2 mutations was significantly correlated with the degree of TP53 disruption (r = 0.804, P = 0.02) and the duration of BTKi therapy (r = 0.851, P = 0.001).[24]

While the emergence of somatic mutations is a well-established mechanism of resistance to BTKi therapy, approximately one-third of patients with clinical resistance do not exhibit detectable mutations in BTK or PLCG2.[24] This finding suggests that resistance may also arise through non-genetic, adaptive mechanisms involving the activation of alternative pro-survival signaling pathways in CLL cells. In particular, the PI3K, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways have been implicated in supporting leukemic cell survival despite BTK inhibition.[25]

Moreover, microenvironmental factors — such as enhanced chemokine and integrin signaling driven by the upregulation of chemokine receptors on CLL cells — may further contribute to BTKi resistance.[25]

Collectively, these findings underscore the critical need for ongoing research into therapeutic strategies that target alternative survival pathways. Such approaches may provide a more effective means of overcoming resistance in CLL patients treated with BTKi.[26]

Managing CLL/SLL After BTKi Resistance

In contemporary clinical practice for patients with CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), the dual challenges of treatment-related adverse events and, more critically, disease progression frequently necessitate discontinuation of BTKi therapy.[27] Among these, disease progression constitutes a principal concern, with reported incidence rates ranging from 15% to 30%, depending on the line of therapy.[27] Importantly, a longitudinal analysis spanning a decade documented disease progression in 38% of patients receiving ibrutinib as first-line treatment, highlighting the limitations of long-term BTKi monotherapy in a subset of patients.[28]The emergence of resistance mutations following treatment with covalent BTKis (cBTKis), particularly those affecting the C481S binding site, significantly undermines the efficacy of subsequent cBTKi retreatment. This clinical challenge necessitates a strategic shift toward alternative therapeutic modalities, notably BCL-2 inhibitor (BCL2i)-based regimens and noncovalent BTKis (ncBTKis).[29-34] While BCL2i therapies offer a potential treatment avenue for patients without prior exposure, definitive, high-quality clinical evidence supporting their efficacy in the post-cBTKi setting remains limited and warrants further investigation.

The broad generalizability of the pivotal phase III MURANO tria — which demonstrated superior outcomes for venetoclax plus rituximab in patients with R/R CLL — is constrained in the context of post-cBTKi treatment. This limitation is primarily due to the underrepresentation of patients with prior B-cell receptor inhibitor (BCRi) exposure, who comprised only 3% (n = 5/194) of the study cohort.[29]

Nevertheless, independent studies provide valuable insights into the utility of BCL2i-based strategies following BTKi failure. In a retrospective analysis by Jones et al., venetoclax monotherapy yielded a 65% objective response rate (ORR) and median progression-free survival (PFS) of approximately 25 months in heavily pretreated patients who had progressed on ibrutinib.[31] Similarly, Kater et al. reported a 64% ORR and a median PFS of 23 months among patients with prior BCRi exposure treated with venetoclax monotherapy.[30]

Real-world data further support these findings. The CLL Collaborative Study of Real-World Evidence (CORE) reported that 14% of patients initiating cBTKi therapy subsequently received BCL2i-based regimens, with 8.9% receiving venetoclax monotherapy. The median time to the next treatment (TTNT) in this cohort was approximately 30 months.[32] Consistently, a mono-institutional series from the Mayo Clinic observed a median TTNT or discontinuation (TTNT-D) of 30 months following venetoclax initiation in patients with cBTKi-resistant CLL.[33]

Comparable outcomes have also been observed with the noncovalent BTKi (nc-BTKi) pirtobrutinib. In the BRUIN CLL-321 trial, a phase 1/2 study comparing pirtobrutinib to the investigator’s choice in patients previously treated with covalent BTK inhibitors (cBTKis) — 85% of whom discontinued due to disease progression — the median TTNT was 25 months.[34] Furthermore, a recent matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC) analysis indicated comparable efficacy between pirtobrutinib and continuous venetoclax monotherapy in R/R CLL patients with prior cBTKi exposure.[35]

Although therapeutic strategies involving BCL-2 inhibitor-based regimens and ncBTK inhibitors have demonstrated promising clinical activity, outcomes for patients with CLL who progress following cBTKi therapy remain suboptimal. These findings highlight a significant and ongoing unmet clinical need in the post-cBTKi treatment setting, emphasizing the necessity for continued research into more durable and mechanistically novel therapeutic approaches.

Variant BTK Mutations and Their Role in Resistance to Second-Generation BTKis

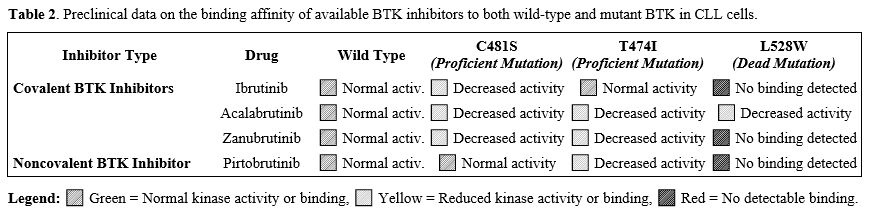

In addition to well-characterized BTK and PLCG2 mutations, the emergence of novel mutations has been observed with the increasing use of second-generation BTKis. Within this evolving therapeutic landscape, BTK mutations in CLL can be broadly classified into two functional categories: kinase-proficient mutations — such as T474I/S and C481S — and kinase-impaired mutations, which include M437R, V416L, C481Y/R/F, and L528W.[25,36-37] Notably, despite reduced or absent kinase activity, many kinase-impaired variants retain the ability to propagate downstream signaling.Among these, the L528W mutation is of particular interest. Preclinical studies have shown that CLL cells harboring this mutation maintain activation of phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ), suggesting that BCR-mediated signaling remains functionally intact even in the context of impaired BTK kinase activity.[25] This observation implies a more complex mechanism of signal transduction in cells expressing the L528W variant, likely involving compensatory or parallel signaling pathways.[25]

Emerging preclinical evidence indicates that kinases such as hematopoietic cell kinase (HCK) and integrin-linked kinase (ILK) may contribute to these alternative pro-survival signaling mechanisms in CLL cells with the L528W mutation.[25,38] These findings highlight the need for further mechanistic studies to elucidate the full spectrum of signaling networks that sustain CLL cell viability in the presence of kinase-impaired BTK variants.

Researchers at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center were the first to identify the BTK L528W mutation in four patients with CLL who experienced disease progression during zanubrutinib therapy.[39] A subsequent study corroborated these findings, detecting the L528W mutation in 7 (53.8%) of 13 patients with disease progression on zanubrutinib, in contrast to only 1 (4.1%) of 24 patients progressing on ibrutinib.[40] Similarly, in the ALPINE study — which utilized a highly sensitive mutation detection assay — non-C481 mutations were observed in 12.5% (3/24) of zanubrutinib-treated patients (L528W: n = 2; A428D: n = 1), while no such mutations were identified among patients receiving ibrutinib.[18]

In addition to the L528W mutation, the BTK T474I gatekeeper mutation has emerged as a significant resistance mechanism in patients undergoing acalabrutinib treatment. Researchers at Ohio State University reported the initial case associating the T474I mutation with acalabrutinib therapy.[41] Furthermore, a comprehensive analysis from the ELEVATE-RR trial identified the T474I mutation in 29% of patients who experienced disease progression while receiving acalabrutinib.[24]

Preclinical data indicate that the T474I, a kinase-proficient mutation exhibiting enhanced autophosphorylation relative to wild-type BTK, maintains active signaling capacity.[25,42] Moreover, in vitro studies suggest that T474 mutations, especially when co-occurring with the C481S mutation, may synergistically enhance BTK enzymatic activity. However, this combined mutation profile has not yet been validated in clinical specimens.[25,42]

Noncovalent BTKis and the Growing Recognition of Non-C481 Mutations

The advent of nc-BTKis represents a promising therapeutic alternative to traditional irreversible cBTKis.[34,43] In contrast to covalent inhibitors, which irreversibly bind to the C481 residue of BTK, ncBTKis interact reversibly within the ATP-binding pocket, enabling sustained inhibition independent of C481 mutation status.[44] These agents are characterized by distinct pharmacologic profiles, including extended half-lives and favorable binding kinetics, which may enhance their therapeutic potential in patients with resistance to covalent BTKis.[43]Among the most clinically advanced agents in this class, pirtobrutinib has demonstrated robust efficacy in R/R CLL, including in patients harboring BTK C481 mutations. The phase I/II BRUIN study reported meaningful clinical responses in patients previously treated with cBTKis, underscoring the therapeutic potential of pirtobrutinib in the R/R CLL setting.[34,43]

More recently, results from the BRUIN CLL-321 trial (NCT04666038) — the first randomized phase III study evaluating pirtobrutinib in patients with prior cBTKi exposure — were presented at the 2024 ASH meeting.[45] This trial demonstrated a significant PFS benefit with pirtobrutinib compared to the investigator's choice of therapy (median PFS: 14.0 months vs. 8.7 months, respectively). Notably, clinical benefit was observed across a range of high-risk subgroups, including patients with BTK C481S and PLCG2 mutations.[45]

Comparable efficacy has been observed with other noncovalent BTKis. In the phase I/II BELLWAVE-001 trial, nemtabrutinib achieved an ORR of 56% in patients with R/R CLL, with a median duration of response (DOR) of 24.4 months and a median PFS of 26.3 months.[46] Notably, 95% of participants had prior covalent BTKi exposure, and BTK^C481S mutations were present in 63% of patients.[47] In contrast, vecabrutinib demonstrated more limited efficacy. A phase Ib dose-escalation study (NCT03037645) enrolled 39 patients with B-cell malignancies — predominantly CLL (77%) — all of whom had received prior BTKi therapy. Among them, 45% harbored BTKC481 mutations, and 18% had PLCG2 mutations. However, the anti-tumor activity observed at studied dose levels was deemed insufficient to warrant phase II expansion, underscoring the variability in clinical activity among noncovalent BTKis.[48]

Finally, fenebrutinib (formerly GDC-0853), a reversible ncBTKi, has been evaluated in a phase 1 trial (NCT01991184) involving 24 patients, 25% of whom carried BTK^C481S mutations. The trial reported an ORR of 33%, with a higher response rate of 50% among patients with CLL (n = 7).[49] Although development for B-cell malignancies has been discontinued, fenebrutinib is currently being studied in other indications, such as multiple sclerosis (NCT04544449).

It is noteworthy that a subset of patients exhibited acquired resistance to pirtobrutinib. Recent investigations have elucidated mechanisms of resistance, including the emergence of novel BTK mutations occurring outside the canonical C481 binding domain.[36,42] A post-hoc analysis of the BRUIN CLL-321 cohort revealed that a substantial proportion of patients (68%) developed acquired mutations upon disease progression, with BTK mutations identified in 44% and PLCγ2 mutations in 24%. Within the cohort of patients with acquired BTK mutations, the T474 and L528W substitutions were prevalent.[50] Given the established association of these mutations with resistance to second-generation BTK inhibitors acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, their emergence may confer cross-resistance to this class of agents as well as to pirtobrutinib.[36,42] Interestingly, several of these resistance-associated BTK mutations (e.g., V416L, A428D, M437R, L528W) demonstrated reduced kinase activity yet paradoxically sustained BCR signaling and AKT pathway activation, suggesting a kinase-independent scaffolding role for BTK in these contexts.[25]

Conclusions

Notably, the field of BTK mutation research is progressing towards a model wherein resistance profiling may assume a pivotal role in guiding therapeutic decision-making, thereby enabling a more personalized and targeted approach to CLL management.[52] Data concerning the binding moieties of BTK inhibitors have revealed that non-C481 BTK mutants, specifically V416L, A428D, M437R, T474I, and L528W, not only confer resistance to the noncovalent inhibitor pirtobrutinib but also extend this resistance to both covalent (ibrutinib) and other noncovalent BTK inhibitors (nemtabrutinib, vecahrutinib, and fenebrutinib).[53-54] Mechanistically, these resistance-conferring mutations (V416L, A428D, M437R, and L528W) have been associated with decreased BTK kinase activity, as evidenced by the absence of BTK Y223 phosphorylation.[25,54] Intriguingly, despite this diminished BTK activation, downstream signaling pathways involving AKT and ERK, alongside hyperactivated calcium release, were sustained even in the presence of BTK inhibition.[54]

The unresolved question of whether pirtobrutinib should be integrated into earlier lines of therapy, including frontline treatment or prior to the administration of cBTKi, is currently being addressed by an ongoing clinical trial (NCT05254743) comparing pirtobrutinib with ibrutinib in previously untreated patients with CLL. The anticipated data from this trial will be crucial in determining the efficacy and safety profile of pirtobrutinib in the frontline setting. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that all patients exhibiting BTK L528W or T474I mutations following pirtobrutinib resistance had prior exposure to ibrutinib, leaving it uncertain whether similar mutations would arise in patients receiving pirtobrutinib as their initial BTKi therapy.[50,54] Of note, nemtabrutinib, the second noncovalent BTK inhibitor (ncBTKi) most extensively studied in clinical trials after pirtobrutinib, is not anticipated to exhibit efficacy against either the T474I or L528W mutations.[54]

From a clinical perspective, given the elevated probability of detecting BTK mutations in patients refractory to BTKis, mutational status warrants meticulous evaluation as a standard in clinical practice.[52] Consequently, therapeutic decision-making for patients exhibiting BTK inhibitor resistance should be guided by their specific mutational profile, thereby enabling the selection of treatment options that are unlikely to be affected by the same resistance mechanisms (Table 2).

|

|

Adoption of fixed-duration therapeutic protocols is a significant strategy to impede the emergence of acquired BTK mutations.[55] The CAPTIVATE study demonstrated that a fixed-duration combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax mitigates the selective pressures associated with continuous BTK inhibition, consequently averting the emergence of detectable BTK mutations upon relapse in CLL.[56] Current clinical investigations assessing various combinations of acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib may further optimize future treatment paradigms.[57-59]

Considering the complexity of BTK inhibitor resistance mechanisms, the advancement of next-generation BTK inhibitor therapy remains a critical area of research. Key findings from the 2024 American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting, particularly from the CadAnCe-101 and NX-5948-301 trials, underscore the potential of these novel agents in treating heavily pretreated CLL/SLL patients who have developed resistance to conventional BTK inhibitors.[60-61] These trials suggest that targeting the BTK pathway through innovative mechanisms, such as E3 ligase-mediated degradation, may provide a viable therapeutic alternative for high-risk, relapsed/refractory CLL patients. The emerging safety and efficacy data from these trials indicate that these novel agents may play a pivotal role in the evolution of treatment regimens for CLL/SLL. Although protein degraders were initially believed to circumvent resistance associated with BTK mutations, recent evidence suggests that a mutation within the BTK kinase domain can compromise the activity of a BTK degrader under clinical evaluation. Notably, patients with CLL cells harboring the A428D BTK mutation may exhibit diminished sensitivity to treatment with BGB-16673 or NX-2127.[62]

Another active area of investigation includes the potential use of T-cell-engaging therapies in heavily treated CLL patients with associated BTK mutations. Clinical investigations have demonstrated the capacity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells to elicit sustained remissions, exhibiting favorable overall response rates in such patients.[63-64] Furthermore, bispecific antibodies are under investigation as immunotherapeutic approaches, revealing encouraging preclinical and preliminary clinical findings in the effective targeting of CLL cells.[65-66] A significant impediment in the application of T-cell-based therapies for CLL is the acquired T-cell impairment observed in affected individual.[67] To address these limitations, current research is exploring strategies such as the integration of targeted pharmacological agents with cellular immunotherapies, the modification of CAR constructs, and the incorporation of immunomodulatory compounds within the manufacturing protocol.[68]

References

- Byrd JC, Brown JR, O'Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib

versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N

Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):213-223. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1400376 PMid:24881631 PMCid:PMC4134521

- Burger

JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for

patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med.

2015;373(25):2425-2437. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1509388 PMid:26639149 PMCid:PMC4722809

- Woyach

JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus

chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med.

2018;379(26):2517-2528. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1812836 PMid:30501481 PMCid:PMC6325637

- Shanafelt

TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy

for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):432-443. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817073

- Sharman

JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, et al. Efficacy and safety in a 4-year

follow-up of the ELEVATE-TN study comparing acalabrutinib with or

without obinutuzumab versus obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in

treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia.

2022;36(4):1171-1175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01485-x PMid:34974526 PMCid:PMC8979808

- Tam

CS, Brown JR, Kahl BS, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and

rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small

lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): a randomized, controlled, phase 3

trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(8):1031-1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00293-5 PMid:35810754

- Byrd

JC, Hillmen P, Ghia P, et al. Acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in

previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of the first

randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(31):3441-3452. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01210 PMid:34310172 PMCid:PMC8547923

- Brown

JR, Eichhorst B, Hillmen P, et al. Zanubrutinib or ibrutinib in

relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med.

2023;388(4):319-332. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2211582 PMid:36511784

- Eichhorst

B, Ghia P, Niemann CU, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline interim

update on new targeted therapies in the first line and at relapse of

chronic lymphocytic leukemia.Ann Oncol. Ann Of Oncol. 2024

Sep;35(9):762-768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2024.06.016

- NCCN

Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Version

1.2025. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. -.

2024 Oct 1. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cll.pdf

- Woyach

JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al. BTK(C481S)-mediated resistance to

ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol.

2017;35(13):1437-1443. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2282 PMid:28418267 PMCid:PMC5455463

- Gruessner

C, Wiestner A, Sun C. Resistance mechanisms and approach to chronic

lymphocytic leukemia after BTK inhibitor therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2025

Feb 19:1-13. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2025.2466101. Online ahead of print.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2025.2466101

- Jones

D, Woyach JA, Zhao W, et al. PLCG2 C2 domain mutations co-occur with BTK and PLCG2

resistance mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia undergoing

ibrutinib treatment. Leukemia. 2017; 31:1645-47. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2017.110 PMid:28366935

- Woyach

JA, Ghia P, Byrd JC, et al. B-cell receptor pathway mutations are

infrequent in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia on continuous

ibrutinib therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(16):3065-3073. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-3887 PMid:37314786 PMCid:PMC10425728

- Skarbnik

AP, Danilov AV, Hoffmann M, et al Mutations in the Bruton Tyrosine

Kinase (BTK) Gene in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Receiving BTK Inhibitors (BTKis). Blood 2024, 144 (Supplement 1): 4623.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-209590

- Bonfiglio

S, Sutton LA, Ljungström V, et al. BTK and PLCG2 remain unmutated in

one third of patients with CLL relapsing on ibrutinib. Blood Adv.

2023;7(12):2794-2806. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008821 PMid:36696464

- Woyach

JA, Jones D, Jurczak W, et al Mutational profile in previously treated

patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia progression on acalabrutinib

or ibrutinib. Blood 2024 Sep 5;144(10):1061-1068. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023023659 PMid:38754046 PMCid:PMC11406168

- Brown

JR, Li J, Eichhorst B, Lamanna N, et al ACQUIRED MUTATIONS IN PATIENTS

WITH RELAPSED/REFRACTORY CLL WHO PROGRESSED IN THE ALPINE STUDY. Blood

Adv. 2025 Jan 24:bloodadvances.2024014206. doi:

10.1182/bloodadvances.2024014206. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2024014206 PMid:39853273 PMCid:PMC12008693

- Quinquenel

A, Fornecker LM, Letestu R, et al. Prevalence of BTK and PLCG2

mutations in a real-life CLL cohort still on ibrutinib after 3 years: a

FILO group study. Blood. 2019;134(7):641-644. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000854 PMid:31243043

- Woyach

J, Huang Y, Rogers K, et al. Resistance to acalabrutinib in CLL is

mediated primarily by BTK mutations [abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(suppl

1):504. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-127674

- Kanagal-Shamanna

R, Jain P, Patel KP, et al Targeted multigene deep sequencing of Bruton

tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant chronic lymphocytic leukemia with

disease progression and Richter transformation. Cancer 2019 Feb

15;125(4):559-574. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31831 PMid:30508305

- Bodor

C, Kotmayer L, Laszlo T, et al Screening and monitoring of the BTKC481S

mutation in a real-world cohort of patients with relapsed/refractory

chronic lymphocytic leukaemia during ibrutinib therapy. Br J Haematol.

2021 Jul;194(2):355-364. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.17502 PMid:34019713

- Sarma

A, Evans C, Dalal S, et al Molecular Analysis at Relapse of Patients

Treated on the Ibrutinib and Rituximab Arm of the National Multi-Centre

Phase III FLAIR Study in Previously Untreated CLL Patients. [abstract]

Blood 2023, 142: (Supplement 1); 4636 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2023-188597

- Molica

S, Allsup D, Giannarelli D. Prevalence of BTK and PLCG2 Mutations in

CLL Patients With Disease Progression on BTK Inhibitor Therapy: A

Meta-Analysis. Am J Hematol. 2025 Feb;100(2):334-337. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.27544

- Montoya

S, Bourcier J, Noviski M, et al. Kinase-impaired BTK mutations are

susceptible to clinical-stage BTK and IKZF1/3 degrader NX-2127.

Science. 2024;383(6682):eadi5798. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi5798 PMid:38301010 PMCid:PMC11103405

- Mato

AR, Shah NN, Jurczak W, et al Pirtobrutinib in relapsed or refractory

B-cell malignancies (BRUIN): a phase 1/2 study. Lancet 2021 Mar

6;397(10277):892-901. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00224-5 PMid:33676628

- Shadman M, Manzoor BS, Sail K, et Treatment Discontinuation Patterns for Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in Real-World Settings: Results From a Multi-Center International Study. Shadman M, Manzoor BS, Sail K, et Treatment Discontinuation Patterns for Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in Real-World Settings: Results From a Multi-Center International Study.

- Itsara

A, Sun C, Bryer E, et al. Long-term outcomes in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia treated with ibrutinib: 10-year follow-up of a phase 2 study.

Presented at the 65th American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual

Meeting & Exposition, December 9-12, 2023; San Diego, CA: Abstract

201. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2023-182397

- Kater

AP, Harrup RA, Kipps TJ, et al The MURANO study: final analysis and

retreatment/crossover substudy results of VenR for patients with

relapsed/refractory CLL. Blood. 2025 Feb 26:blood.2024025525. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024025525 PMid:40009494

- Kater

AP, Arslan Ö, Demirkan F, et al. Activity of venetoclax in patients

with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: analysis of

the VENICE-1 multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 3b trial.

Lancet Oncol. 2024 Apr;25(4):463-473. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00070-6 PMid:38467131

- Jones

JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic

leukemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a

multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):65-75.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30909-9

PMid:29246803

- Ghosh

N, Eyre TA, Brown JR, Lamanna N, et al Treatment Effectiveness of

Venetoclax-Based Therapy After Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: An International Real-World Study. Am J

Hematol. 2025 Mar;100(3):511-515. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.27563 PMid:39698781 PMCid:PMC11803543

- Hampel

PJ, Rabe KG, Guieze R, et al Outcomes with Venetoclax-Based Treatment

in Patients with Covalent Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor

(cBTKi)-Treated, Chemotherapy-Naïve Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL):

An International Retrospective Study. Blood (2024) 144 (Supplement 1):

1856. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-198200

- Mato AR, Woyach JA, Brown JR, et al Pirtobrutinib after a Covalent BTK Inhibitor in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2023 Jul 6;389(1):33-44.

- Al-Sawaf O, Jen MH, Hess LM, et al Pirtobrutinib versus venetoclax in covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor-pretreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Haematologica 2024 Jun 1;109(6):1866-1873. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.284150 PMid:38031799 PMCid:PMC11141664

- Wang

E, Mi X, Thompson MC, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to noncovalent

Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(8):735-743.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2114110 PMCid:PMC9074143

- Naeem

A, Utro F, Wang Q, et al. Pirtobrutinib targets BTK C481S in

ibrutinib-resistant CLL but second-site BTK mutations lead to

resistance. Blood Adv. 2023;7(9):1929-1943. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008447 PMid:36287227 PMCid:PMC10202739

- Dhami

K, Chakraborty A, Gururaja TL, et al. Kinase-deficient BTK mutants

confer ibrutinib resistance through activation of the kinase HCK. Sci

Signal. 2022;15(736):eabg5216. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.abg5216 PMid:35639855

- Handunnetti

S, Tang C, Nguyen T, et al. BTK Leu528Trp - a potential secondary

resistance mechanism specific for patients with chronic lymphocytic

leukemia treated with the next generation BTK inhibitor zanubrutinib

[abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):170 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-125488

- Blombery

P, Thompson ER, Lew TE, et al. Enrichment of BTK Leu528Trp mutations in

patients with CLL on zanubrutinib: potential for pirtobrutinib

cross-resistance. Blood Adv. 2022;6(20):5589-5592. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008325 PMid:35901282 PMCid:PMC9647719

- Woyach

J, Huang Y, Rogers K, et al. Resistance to acalabrutinib in CLL is

mediated primarily by BTK mutations [abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(suppl

1):504. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-127674

- Tam

CS, Balendran S, Blombery P. Novel mechanisms of resistance in CLL:

variant BTK mutations in second-generation and noncovalent BTK

inhibitors. Blood. 2025 Mar 6;145(10):1005-1009 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024026672 PMid:39808800

- Mato

AR, Shah NN, Jurczak W, et al. Pirtobrutinib in relapsed or refractory

B-cell malignancies (BRUIN): a phase 1/2 study. Lancet.

2021;397(10277):892-901. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00224-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00224-5 PMid:33676628

- Shaffer

AL, III, Phelan JD, Wang JQ, et al. Overcoming acquired epigenetic

resistance to BTK inhibitors. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2:630-647. https://doi.org/10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0063 PMid:34778802 PMCid:PMC8580621

- Sharman

JP, Munir T, Grosicki S, et al. 886 BRUIN CLL-321: Randomized Phase III

Trial of Pirtobrutinib Versus Idelalisib Plus Rituximab (IdelaR) or

Bendamustine Plus Rituximab (BR) in BTK Inhibitor Pretreated Chronic

Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma. Abstract presented at:

American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition; December

9, 2024; San Diego, CA. Abstr 886. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-198147

- Woyach

JA, Stephens DM, Flinn IW, et al First-in-Human Study of the Reversible

BTK Inhibitor Nemtabrutinib in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancer

Discov. 2024 Jan 12;14(1):66-75. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-0670

- Woyach

J, Flinn IW, Eradat H, et al. Nemtabrutinib (MK-1026), a noncovalent

inhibitor of wild-type and C481S mutated bruton tyrosine kinase for

B-cell malignancies: efficacy and safety of the phase 2 dose-expansion

BELLWAVE-001 study. HemaSphere. 2022;(6):578-579. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HS9.0000845612.25766.0c

- Allan

JN, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Gladstone DE, et al Phase Ib dose-escalation study

of the selective, noncovalent, reversible Bruton's tyrosine kinase

inhibitor vecabrutinib in B-cell malignancies. Haematologica. 2022 Apr

1;107(4):984-987. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2021.280061 PMid:34937320 PMCid:PMC8968902

- Byrd

JC, Smith S, Wagner-Johnston N, et al First-in-human phase 1 study of

the BTK inhibitor GDC-0853 in relapsed or refractory B-cell NHL and

CLL. Oncotarget. 2018 Jan 22;9(16):13023-13035. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24310 PMid:29560128

- Brown

J, Desikan S, Nguyen B, et al. Genomic evolution and resistance during

pirtobrutinib therapy in covalent BTK-inhibitor (cBTKi) pretreated

chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients: updated analysis from the BRUIN

study [abstract]. Blood. 2023;142(suppl 1):326. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2023-180143

- Massoni-Badosa

R, Schiffman JS, Pradhan B, et al Topic Modeling of Genotyping of

Transcriptomes Reveals Collaboration between BTKC481S-Mutant and Wild

Type Cells in Btki-Resistant Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood (2024)

144 (Supplement 1): 4610. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-205727

- Gruessner

C, Wiestner A, Sun C. Resistance mechanisms and approach to chronic

lymphocytic leukemia after BTK inhibitor therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2025

Feb 19:1-13. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2025.2466101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2025.2466101 PMid:39972943

- Qi

J, Endres S, Yosifov DY, et al. Acquired BTK mutations associated with

resistance to noncovalent BTK inhibitors. Blood Adv.

2023;7(19):5698-5702. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008955 PMCid:PMC10539862

- Montoya

S, Thompson MC. Noncovalent Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in the

Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jul

17;15(14):3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15143648

- Molica

S, Allsup D. Fixed-duration therapy comes of age in CLL: long-term

results of MURANO and CLL14 trials. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2024

Mar-Apr;24(3-4):101-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2023.2288899 PMid:38014557

- Jain

N, Croner LJ, Allan JN, et al. Absence of BTK, BCL2, and

PLCG2 Mutations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Relapsing after

First-Line Treatment with Fixed-Duration Ibrutinib plus Venetoclax.

Clin Cancer Res. 2024 Feb 1;30(3):498-505. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-3934 PMCid:PMC10831330

- Brown

JR, Seymour JF, Jurczak W, et al. Fixed-Duration Acalabrutinib Combinations in

Untreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Engl J Med. 2025 Feb

20;392(8):748-762. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2409804

- Ma S, Munir T, Lasica M, et al. Combination of zanubrutinib + venetoclax for treatment-naive CLL/SLL with del(17p) and/or TP53: preliminary results from SEQUOIA arm D. Presented at: 2024 EHA Congress; June 13-16, 2024; Madrid, Spain. Abstract S160.

- Roeker

LE, Woyach JA, , Cheah CY, et al Fixed-duration pirtobrutinib plus

venetoclax with or without rituximab in relapsed/refractory CLL: the

phase 1b BRUIN trial. Blood (2024) 144 (13): 1374-1386. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024024510 PMid:38861666 PMCid:PMC11451378

- Thompson MC, Parrondo RD, Frustaci AM, et al. Preliminary efficacy and safety of the Bruton tyrosine

kinase degrader BGB-16673 in patients with relapsed or refractory

chronic lymphocytic Leukemia/Small lymphocytic lymphoma: results from

the phase 1 CaDAnCe-101 study. Blood. 2024;144:885. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-199116

- Shah NN, Omer Z, Collins GP, et al. Efficacy and safety of the Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK)

degrader NX-5948 in patients with Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) chronic

lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): updated results from an ongoing phase 1a/b

study. Blood. 2024;144:884. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-194839

- Wong

RL, Choi MY, Wang HY, et al. Mutation in Bruton Tyrosine Kinase (BTK)

A428D confers resistance To BTK-degrader therapy in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia. Leukemia. 2024 Aug;38(8):1818-1821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02317-4 PMid:39048721 PMCid:PMC11286506

- Davids

MS; Kenderian SS; Flinn IW, et al. ZUMA-8: A

Phase 1 Study of KTE-X19, an Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)

T-Cell Therapy, in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Chronic

Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2022, 140, 7454-7456. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-167868

- Siddiqi

T, Maloney DG, Kenderian SS, et al.

Lisocabtagene maraleucel in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small

lymphocytic lymphoma (TRANSCEND CLL 004): A multicentre, open-label,

single-arm, phase 1-2 study. Lancet 2023, 402, 641-654. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01052-8

- Kater

AP, Christensen JH, Bentzen HH, et al. Subcutaneous

Epcoritamab in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic

Leukemia: Preliminary Results from the Epcore CLL-1 Trial. Blood 2021,

138, 2627. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-146563

- Eichhorst

B, Eradat H, Niemann CU, et al. Epcoritamab Monotherapy and Combinations in

Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia or Richter's

Syndrome: New Escalation and Expansion Cohorts in Epcore Cll-1.

Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 41, 828-829. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.3166_OT10

- Vlachonikola

E, Stamatopoulos K, Chatzidimitriou A.T Cell Defects and Immunotherapy

in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Jun

29;13(13):3255. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133255. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13133255 PMid:34209724 PMCid:PMC8268526

- Kater AP, Siddiqi T. Relapsed/refractory CLL: the role of allo-SCT, CAR-T, and T-cell engagers. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2024 Dec 6;2024(1):474-481. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2024000570. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2024000570 PMid:39644060 PMCid:PMC11665508