Syphilis is known as a ‘great mimic’ since it can show a wide spectrum of manifestations, particularly within dermatological presentations and among immunocompromised individuals.[6] The primary stage of the disease is characterized by the presence of an ulcer (chancre) that may appear on the genitals, anus, mouth, or throat, and that presents as a nodular, roundish, hard to the touch, painless, dark red lesion.[2] As this lesion often goes unnoticed, patients often present during the secondary stage.[2] The most frequent manifestation of secondary syphilis is rash, which often exhibits in its typical pattern with a diffuse, symmetric macular or papular eruption involving the entire trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles. Six so-called atypical skin patterns were identified, making the diagnosis of syphilis challenging.[7] They can be clustered in pustular, annular, framboesiform, nodular-ulcerative (lue maligna), nodular, and psoriasiform. Late-stage or tertiary syphilis occurs many years after infection if the disease has not been treated, and it can affect any organ.[2] The most severe manifestations, which can cause death, are those affecting the cardiovascular system and central nervous system, while milder ones affect the skin.[2] Bones, tendons, stomach, liver, spleen, and lungs may also be affected at this stage.[2] Larger studies have suggested that although there are some differences in clinical manifestations among PLWH compared with those without HIV, clinical manifestations are, for the most part, similar at each stage, regardless of HIV serostatus.[8] However, PLWH may exhibit a higher prevalence of specific features, including multiple chancres, overlapping manifestations of different syphilis stages, increased frequency of ulceronodular lesions, and a greater incidence of ocular and neurological involvement.[8]

Given its rising prevalence and the severe implications associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment, it is imperative to ensure the accurate and prompt recognition of syphilis at all stages of the disease. This task becomes particularly challenging in cases of secondary syphilis, where cutaneous manifestations exhibit a broad spectrum of clinical presentations. The diagnostic complexity is further heightened in PLWH due to the wide range of potential differential diagnoses in this population. Herein, we report the case of a 60-year-old male living with HIV presenting atypical skin lesions that were attributed to multifaceted disseminated syphilis, as well as a comprehensive review of the prior literature of cases of secondary syphilis with atypical cutaneous manifestations.

Case Description

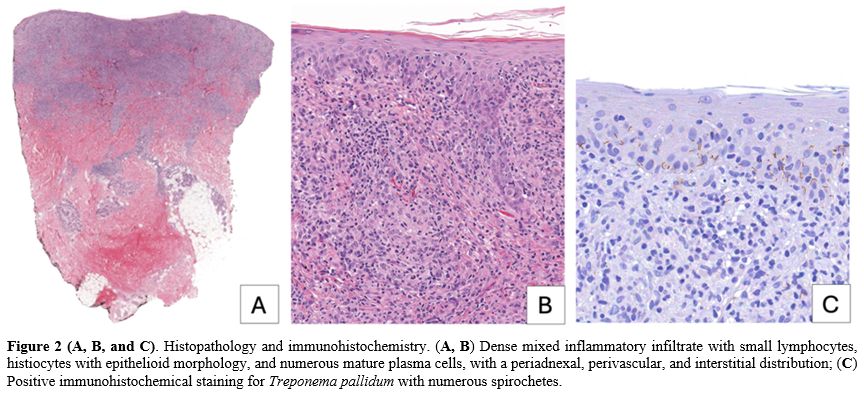

A 60-year-old Caucasian male presented to the outpatient clinic of our Infectious Diseases Unit (Spedali Civili Hospital, Brescia, Italy) with a one-month history of intermittent fever, dry cough, and the onset of diffuse skin lesions without itching over the past 10 days (Figure 1). The patient had a known history of HIV acquisition, diagnosed in 2001, for which he had irregular follow-up at our unit. The patient had a history of high-risk behaviors: he is an MSM with multiple sexual partners and previous substance abuse. His medical history also included a multi-metameric herpes zoster infection in 2006, latent syphilis treated in 2012, and an occult HBV infection. He began antiretroviral therapy (ART) in 2012 but had inconsistent adherence, with the last ART dose taken two years prior to the current presentation and consisting of a regimen of dolutegravir (DTG), abacavir (ABC), and lamivudine (3TC) initiated approximately five years before. On his last examination two years ago, his CD4+ cell count was 390 cells/mcL (CD4% 14.6), with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 0.24, and his HIV-RNA was undetectable (< 50 copies/mL). |

|

The patient denied engaging in any sexual activity in the month prior to symptom onset and noted no similar symptoms in any previous sexual partners. Over the past 30 days, he had been self-administering trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160 mg/800 mg twice daily) alongside symptomatic treatment.

On physical examination, the patient exhibited widespread red-brownish multiform skin lesions on the trunk, including the genitals, limbs, and face, while sparing the palms, soles, and scalp. Lesions were mostly of papule-nodular appearance, with some vesicles and crusts, while in some areas they assumed an annular shape, probably due to coalescence or central resolution. Some lesions were slightly scaling, and no pruritus was reported. No enanthem was present, though oral thrush was noted. No superficial lymphadenopathy was observed.

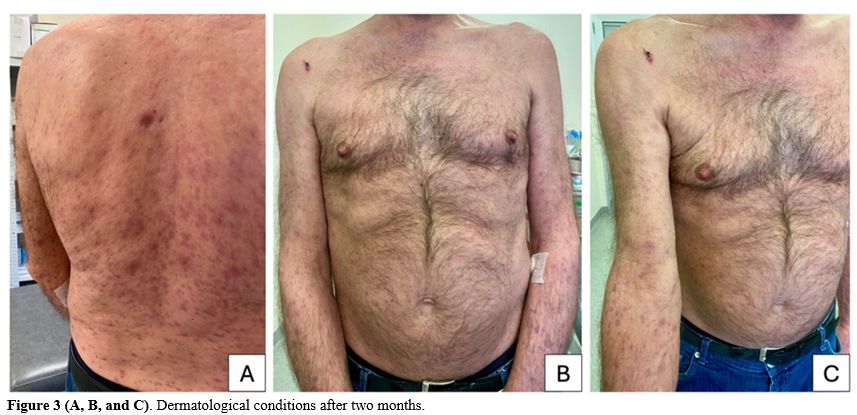

Suspecting monkeypox, nasopharyngeal and skin swabs were negative for monkeypox virus. The cryptococcal antigen test also returned negative. Histoplasma was not investigated as the primary clinical suspicion, and the epidemiological context in Italy rendered its presence unlikely. Laboratory tests revealed a positive chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) for Treponema pallidum-specific antibodies, with a Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) titer of 1:32, which was reactive, in contrast to the non-reactive result from two years prior. To exclude cutaneous lymphoma, a 6 mm punch biopsy was performed on a lesion from the right shoulder, revealing normotrophic and normal keratotic epidermis. The dermis displayed a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of small lymphocytes, histiocytes with epithelioid morphology, and numerous mature plasma cells, with a periadnexal, perivascular, and interstitial distribution. No fungal elements were detected, and immunohistochemical staining for Treponema was positive (Figure 2).

On further investigation, CD4 cell count was 118 cells/mcL (CD4% 12.8), with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 0.16 and a HIV viral load of 5,120,000 copies/mL. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, including an RPR test, was negative, and the quantitative HIV-RNA in CSF was 78,200 copies/ml. A chest and abdominal CT scan identified diffuse mediastinal lymphadenopathy, along with bilateral hilar, axillary, para-aortic, inter-aortocaval, and bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy.

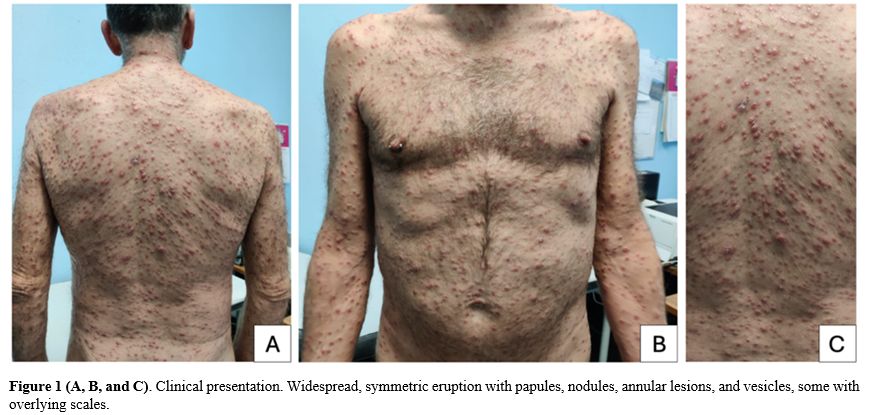

The diagnosis of multifaceted disseminated secondary syphilis was established in the context of poorly controlled HIV. Despite the negative CSF analysis, the patient experienced mental confusion, dizziness, and headache, prompting the initiation of IV penicillin G. Additionally, the regimen with DTG/ABC/3TC was reinitiated. Following the treatment, inflammatory markers significantly decreased, and fever and skin lesions resolved. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, only residual post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation on the trunk and limbs was observed (Figure 3).

Discussion and Narrative Review

Since reaching a historic low in 2000 and 2001, the rate of primary and secondary syphilis has increased almost every year.[9] In 2022, 207,255 cases of all stages of syphilis were reported to the United States CDC, representing an increase of more than 17% since 2021.[10] Rates increased among both males and females, in all regions of the United States, and among all racial/ethnic groups.[8] In a large cross-sectional study conducted in Turkey, syphilis coinfection among PLWH is most common in sexually active young-to-middle-aged men, particularly those who are MSM or bisexual.[4] This discrepancy suggests that unprotected sexual practices and overlapping sexual networks in MSM communities substantially facilitate the transmission of syphilis.[4]Syphilis and HIV have similar modes of transmission, and infection with one may enhance the acquisition and transmission of the other. First, syphilis infection is one of the causes of genital ulcer disease, which disrupts epithelium and mucosa, providing a portal of entry for HIV and facilitating HIV transmission.[11] In addition, this ulceration may result in a local influx of CD4+ lymphocytes.[11] T. pallidum and its constituent lipoproteins were shown to induce the expression of CCR5 on macrophages in syphilitic lesions, thereby increasing the likelihood of HIV transmission.[11] Thus, there is a high rate of HIV coinfection among MSM with syphilis.

Atypical cutaneous presentations of secondary syphilis have been increasingly recognized in the literature. A 10-year retrospective study by Ciccarese et al. reported atypical dermatological manifestations in 25.8% of patients presenting with clinical signs of syphilis.[12] Several risk factors have been associated with atypical cutaneous presentations of syphilis. HIV coinfection is among the most significant, as it may alter the natural course of syphilis, leading to more aggressive, atypical, or overlapping clinical stages.[13] However, this association is not uniformly observed across all studies.[12] Reinfection with T. pallidum has also been implicated, with evidence suggesting that repeated episodes may result in attenuated clinical manifestations and serological responses.[12] Additionally, high non-treponemal antibody titers (e.g., VDRL ≥ 1:32) have been correlated with atypical dermatologic findings.[12]

The most common clinical manifestation of secondary syphilis is cutaneous involvement, often accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.[2] The typical dermatological presentation is a diffuse maculopapular exanthem that usually involves the trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles. These lesions are generally non-pruritic and exhibit a purplish to red-brown hue.[7] A 20-year retrospective study by Abell et al. demonstrated that 40% of syphilitic rashes are macular, 40% are maculopapular, 10% are papular, and the remaining 10% are not easily grouped within these categories.[14]

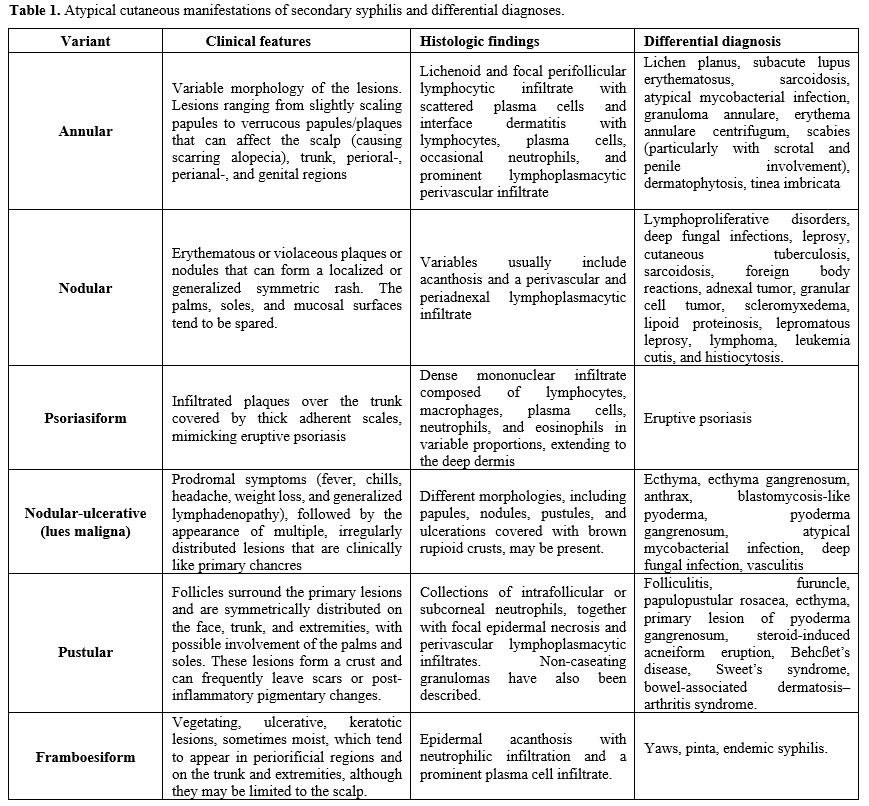

Historically, six principal atypical patterns of secondary syphilis have been described (Table 1). Nevertheless, a clear classification is lacking, leading to inconsistencies in the nomenclature and descriptions of the various clinical manifestations reported across different studies. Additionally, no accurate prevalence data are available. Atypical cutaneous lesions are largely similar in individuals living with HIV and those who are not.[13] However, in PLWH, additional presentations such as mycosis fungoides-like lesions and syphilitic gummas occurring in early stages of infection have been reported.[13] In the present case, the cutaneous involvement was polymorphic, characterized by a combination of papular, nodular, pustular, and annular lesions, reflecting a multifaceted and generalized manifestation of secondary syphilis.

The pathogenesis of atypical cutaneous manifestations is not fully elucidated but may involve immune dysregulation, particularly in the context of HIV coinfection. Nodular and granulomatous lesions may represent a hypersensitivity reaction to T. pallidum.[15] In immunocompromised individuals, a high burden of spirochetes can provoke granuloma formation as part of a dysregulated immune response.[15] In contrast, other histological studies analysing cases of malignant syphilis have reported very few organisms and an excessive inflammatory infiltrate, suggesting an abnormally elevated immune response.[13] Interestingly, even in patients with preserved CD4 cell count (>200 cells/μL), severe and persistent dermatological manifestations such as malignant syphilis have been documented, suggesting that qualitative rather than quantitative immune dysfunction plays a crucial role.[13] An alternative hypothesis suggests that malignant syphilis may result from strains of T. pallidum of increased virulence.[13]

Syphilis diagnosis remains challenging due to the complexity of interpreting serological assays, which remains the standard method for syphilis diagnosis both in PLWH and non-PLWH. Nevertheless, this challenge is particularly evident in PLWH, as serological anomalies are more frequently observed in these patients. These include unusually high titers, false-negative results, and abnormally delayed seroreactivity.[13] Serological response to treatment in coinfection syphilis/HIV is controversial: unusual responses such as serological non-response and the serofast state have been reported.[16] However, evidence suggests that the majority of PLWH infected with syphilis achieve an adequate serologic response after treatment, although the time required to reach this response may be prolonged.[16] Supporting this, rates of serological non-response in PLWH appear to decrease over time, and HIV-related immunodeficiency was hypothesized as the cause of this controversial response.[16] In addition, diagnosis in PLWH can be further complicated by the fact that the primary stage of syphilis may be asymptomatic in PLWH, leading to initial presentation during the secondary stage.[7]

For these reasons, tissue biopsy should be considered.[13] Immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays targeting T. pallidum have demonstrated high diagnostic sensitivity, with some studies reporting a combined sensitivity of approximately 92%.[13] These modalities are especially useful in patients with clinical signs suggestive of syphilis but negative serological results or inconclusive histopathological findings. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the highest prevalence of syphilis is reported in lower-middle-income countries,[17] where access to these diagnostic modalities could be limited due to economic constraints. Consequently, thorough clinical evaluation, the particularly detailed skin examination and the ability to recognize atypical cutaneous manifestations of syphilis become notably significant.

Dermatological expertise is particularly valuable, since approximately 8% of cutaneous syphilitic lesions demonstrate morphology and distributions suggestive of other dermatologic conditions. These include atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, drug-induced eruptions, erythema multiforme, mycosis fungoides, and less common lichenoid lesions.[14]

In the present case, these entities were excluded through serological evaluation and histopathological examination. The spectrum of potential differential diagnoses largely depends on the morphological variant and distribution of the lesions (Table 1). Diagnostic clues such as mucosal ulcerations, palmoplantar involvement, and genital lesions may support the diagnosis of syphilis in atypical cases. In their absence, clinical diagnosis becomes challenging due to the broad differential, even within infectious diseases alone.[9,18]

Regarding neurosyphilis diagnosis, the RPR test in CSF plays an important role and is the gold standard for diagnosis of neurosyphilis, next to the VDRL test in CSF. However, a study by Merins et al. reported that the CSF-RPR test exhibits a sensitivity of only 21% and a specificity of 97% for diagnosing definite or probable neurosyphilis.[19] These findings indicate that up to 80% of neurosyphilis cases could be missed if diagnosis were based solely on this method, underscoring the limitations of CSF-RPR in routine clinical practice.[19] In selected cases, CSF is recommended even in the absence of neurological symptoms. According to CDC guidelines, CSF examination may be considered in PLWH who have latent syphilis of unknown duration or late latent syphilis if they have a CD4 count of ≤350 cells/μL and/or a serum RPR titer of ≥1:32.[20] In addition, failure of non-treponemal titers to decline fourfold within 6-12 months after therapy is a reason to consider lumbar puncture, especially in PLWH.[20]

PLWH should be treated in accordance with the same recommendations as for HIV uninfected patients.[11] Penicillin G administered parenterally is the preferred treatment for syphilis. The CDC recommended regimen for the treatment of primary and secondary syphilis in adults is intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units in a single dose.[11] Benzathine penicillin does not reliably produce detectable levels of penicillin in the CSF; accordingly, this drug cannot be relied on as a treatment of neurosyphilis.[11] To better ensure adequate antibiotic levels in the central nervous system, the recommended regimen of the CDC for the treatment of neurosyphilis is 18-24 million units of aqueous penicillin G per day, administered as 3-4 million units intravenously every four hours, or continuous infusion, for 10-14 days.[11]

In the literature, cases of recurrence or treatment failure of syphilis have been reported among PLWH, even after appropriate therapy.[4] For this reason, current guidelines recommend more frequent serologic follow-up, such as RPR testing every three months, after treatment in PLWH with syphilis.[4]

An unintended consequence of advancements in HIV treatment is the observed complacency in protective sexual behaviors. The “Undetectable = Untransmittable (U = U)” concept represents a breakthrough in HIV/AIDS management.[4] However, the widespread adoption of this message has, in some cases, led to a deprioritization of condom use. While confidence in preventing HIV transmission is well-founded, it does not offer protection against other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as syphilis.[4] Indeed, declining condom use has been cited as one of the contributing factors to the global resurgence of syphilis among HIV-positive populations.[4] Therefore, clinical follow-up for PLWH should emphasize the need for protection not only against HIV, but also against other STIs.[4] Sustained sexual health education is essential for younger PLWH who remain healthy for extended periods under treatment, as even a “treatable” infection like syphilis can lead to serious complications if neglected.[4]

Conclusions

This case highlights key clinical insights. Syphilis presents with a broad spectrum of cutaneous manifestations, with up to six overlapping patterns complicating diagnosis. Therefore, syphilis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any recent, widespread, symmetric skin eruption. A comprehensive medical history, including travel, animal contact, and current therapies, along with a thorough skin examination, is essential for early detection. Once the diagnosis has been confirmed through serological testing, performing a skin biopsy of atypical lesions is also recommended to support the diagnosis of secondary syphilis further. Given the rising incidence of syphilis -at its highest since the 1950s- and the notable increase in congenital syphilis cases, as reported by the CDC, it is crucial to remain vigilant in identifying this condition across diverse patient populations. Early recognition of even atypical manifestations is critical for proper and rapid management of this disease.Authors' Contributions

G.T. and E.Q.-R. contributed to the study's conception and design. I.S., F.C., G.T., and E.Q.-R wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.Ethical Approval

Not applicable. The patient has been duly informed about the study procedures and objectives and has provided written informed consent prior to participation.References

- Stamm LV. Syphilis: Re-emergence of an old foe. Microb Cell. 2016;3(9):363-370. https://doi.org/10.15698/mic2016.09.523 PMid:28357375 PMCid:PMC5354565

- World Health Organization - Syphilis. [(accessed on 29 april 2025)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/syphilis

- CDC

Newsroom Releases. U.S. Syphilis Cases in Newborns Continue to

Increase: A 10-Times Increase Over a Decade. [(accessed on 29 april

2025)]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/s1107-newborn-syphilis.html

- Merdan

S. et al., Burden of syphilis among people living with HIV: a large

cross-sectional study from Türkiye. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.

2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-025-05199-1 PMid:40553368

- Annual epidemiological report for 2023 - syphilis. [(accessed on 03 august 2025)] Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/syphilis-annual-epidemiological-report-2023

- Tiecco

G, Degli Antoni M, Storti S, et al. A 2021 Update on Syphilis: Taking

Stock from Pathogenesis to Vaccines. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):1364.

doi:10.3390/pathogens10111364 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10111364 PMid:34832520 PMCid:PMC8620723

- Balagula

Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, Erdag G, Chien AL. The great imitator

revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of

secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(12):1434-1441. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.12518 PMid:25312512

- Rompalo A, Marrazzo J, Mitty J. Syphilis in persons with HIV. 2024. [(accessed on 03 august 2025)]. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/syphilis-in-persons-with-hiv

- Yu

W, You X, Luo W. Global, regional, and national burden of syphilis,

1990-2021 and predictions by Bayesian age-period-cohort analysis: a

systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Front

Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1448841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1448841 PMid:39211337 PMCid:PMC11357943

- Niu

E, Sareli R, Eckardt P, Sareli C, Niu J. Disparities in Syphilis Trends

and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Joinpoint Analysis of

Florida Surveillance Data (2013-2022). Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69934.

Published 2024 Sep 22. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.69934

- Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. Syphilis and HIV coinfection. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(1):9-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.002 PMid:19237085

- Ciccarese

G, Facciorusso A, Mastrolonardo M, Herzum A, Parodi A, Drago F.

Atypical Manifestations of Syphilis: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. J

Clin Med. 2024;13(6):1603. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061603 PMid:38541829 PMCid:PMC10971508

- Ivars

Lleó M, Clavo Escribano P, Menéndez Prieto B. Atypical Cutaneous

Manifestations in Syphilis. Manifestaciones cutáneas atipícas en la

sífilis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(4):275-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.002 PMid:26708562

- Cervoni GE, By CC, Wesson SK. An atypical syphilis presentation. Cutis. 2017;100(5):E25-E28

- Villaverde

MRD, Villena JPDS, Yap Silva C. A Peculiar Pattern: Nodular Secondary

Syphilis with Granulomatous Dermatitis. Acta Med Philipp.

2024;58(17):60-63. https://doi.org/10.47895/amp.v58i17.9040 PMid:39431263 PMCid:PMC11484585

- Marchese

V, Tiecco G, Storti S, et al. Syphilis Infections, Reinfections and

Serological Response in a Large Italian Sexually Transmitted Disease

Centre: A Monocentric Retrospective Study. J Clin Med.

2022;11(24):7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11247499 PMid:36556115 PMCid:PMC9781386

- Tsuboi

M, Prevalence of syphilis among men who have sex with men: a global

systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000-20. Lancet Glob Health.

2021; https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00221-7 PMid:34246332

- Salvi,

M., Tiecco, G., Rossi, L., Venturini, M., Battocchio, S., Castelli, F.,

& Quiros-Roldan, E. Finger nodules with a papulovesicular hands and

feet eruption: a complicated human Orf virus infection. BMC infectious

diseases, 2024;24(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-08998-7 PMid:38229010 PMCid:PMC10792816

- Merins V, Hahn K. Syphilis and neurosyphilis: HIV-coinfection and value of diagnostic parameters in CSF. Eur J Med Res. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-015-0175-8 PMid:26445822 PMCid:PMC4596308

- Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatments Guidelines. CDC, 2021. [(accessed on 03 august 2025)]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.html