Case Presentation

A 41-year-old woman was diagnosed with adverse-risk AML as per the ELN 2022 classification. She achieved morphologic and minimal residual disease-negative remission following induction chemotherapy. She received the Standard 3+7 Induction protocol followed by 2 cycles of high-dose cytarabine as consolidation while awaiting funds for HSCT. She underwent haploidentical peripheral blood stem cell transplantation using fludarabine, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide (Flu-Bu-Cy) as a Conditioning regimen, followed by post-transplant cyclophosphamide-based GVHD prophylaxis.Discussion

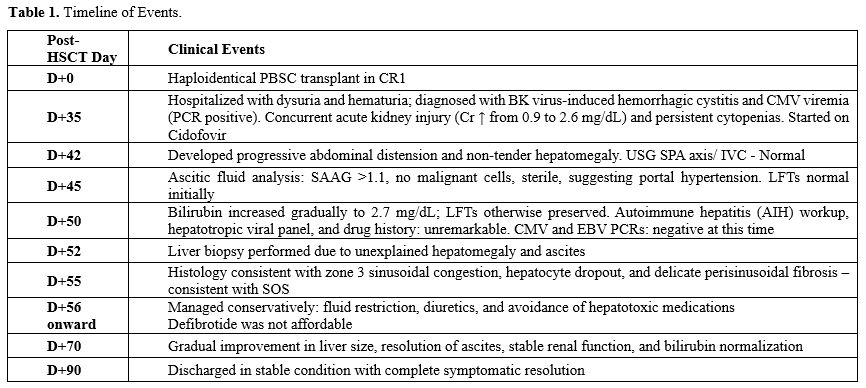

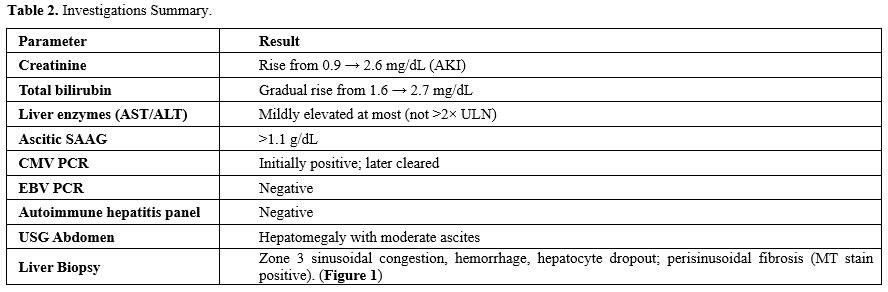

Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS), historically referred to as veno-occlusive disease (VOD), is a well-known yet often under-recognized complication following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Traditionally associated with early post-transplant periods and hyperacute hepatic dysfunction, SOS has expanded in clinical spectrum — particularly in the context of haploidentical transplants, where atypical or delayed presentations are increasingly reported.[1,2]Our patient developed classic features of volume overload — ascites and hepatomegaly — without the expected biochemical storm. Despite being on day +42 post-HSCT, her liver enzymes were near-normal, bilirubin was only modestly elevated, and there was no right upper quadrant pain or weight gain — hallmarks typically seen in classical SOS. In most cases, such a constellation of symptoms would prompt evaluation for infection (CMV/EBV), drug-induced liver injury (cidofovir), or graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) rather than SOS. However, the slow, insidious onset and lack of alternative diagnoses raised suspicion.

This case underscores an important clinical reality: a significant proportion (25–39%) of SOS cases manifest after day +21, a presentation now defined as late-onset SOS.[3,4] Unlike early VOD, these patients may not meet the Baltimore or modified Seattle criteria — both of which rely heavily on early hyperbilirubinemia and tender hepatomegaly.[5] As a result, late-onset VOD may escape early detection, particularly in centers where diagnostic biopsy is deferred due to cytopenias or perceived risks.

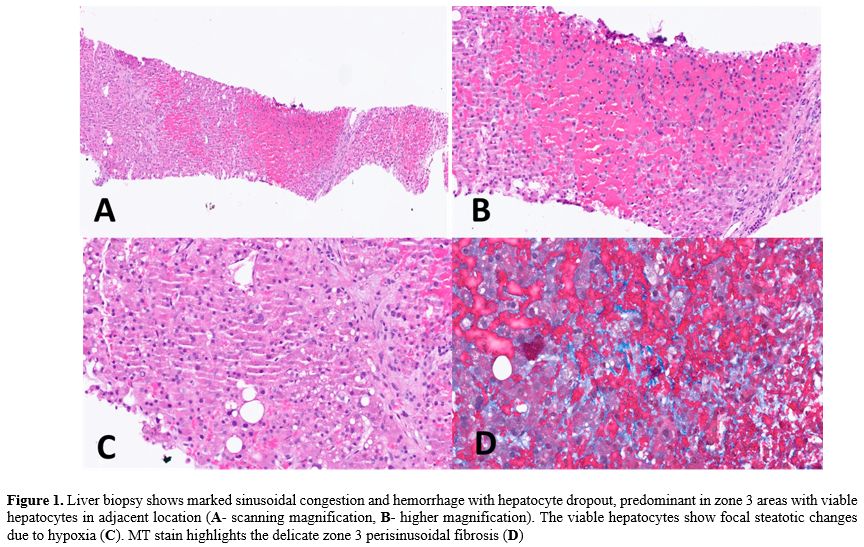

The role of liver biopsy, though invasive, is invaluable in such scenarios. In our patient, histology revealed zone 3 sinusoidal congestion, hepatocyte dropout, and perisinusoidal fibrosis — textbook findings of SOS.[6] The biopsy also helped exclude competing etiologies: no viral inclusions, absence of GVHD features (no bile duct injury or portal lymphocytic infiltration), and no interface activity suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis. Thus, the biopsy transformed diagnostic ambiguity into clinical clarity.

Importantly, defibrotide remains the only FDA- and EMA-approved drug for VOD/SOS, but its use is generally reserved for cases with severe features or multi-organ dysfunction.[7] A pivotal multicenter phase III trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of defibrotide (DF) at a dose of 25 mg/kg/day in 102 patients with severe sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease (SOS/VOD), with a median age of 21 years (range 0–72). A historical control group consisting of 32 patients was used for comparison. Treatment with defibrotide was associated with significantly improved clinical outcomes. The complete response (CR) rate was 24% in the DF group compared to 9% in the control group (p = 0.013), and Day +100 overall survival (OS) was 38% versus 25%, respectively (p = 0.034). The incidence of adverse events, including hemorrhagic toxicity (65% in the DF group vs. 69% in controls), did not differ significantly between the groups.[8] Based on these results, the recommended dose of defibrotide is 25 mg/kg/day, as approved by both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Treatment should be continued for a minimum of 21 days and until all clinical signs and symptoms of SOS/VOD have resolved. No dose adjustment is necessary for patients with renal impairment. In obese patients, corrected body weight should be used for dose calculation. Although defibrotide is generally well tolerated, a small risk of anaphylaxis exists and should be considered in clinical practice.[9]

Based on these results, the recommended dose of defibrotide is 25 mg/kg/day, as approved by both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Treatment should be continued for a minimum of 21 days and until all clinical signs and symptoms of SOS/VOD have resolved. No dose adjustment is necessary for patients with renal impairment. In obese patients, corrected body weight should be used for dose calculation. Although defibrotide is generally well tolerated, a small risk of anaphylaxis exists and should be considered in clinical practice.

Our patient, diagnosed early due to heightened suspicion and tissue confirmation, given financial constraints and the absence of severe clinical features, was managed conservatively without defibrotide. This aligns with observational data suggesting that patients with milder disease — particularly those identified early — may recover with supportive care alone.[7,10]

Finally, it is worth noting that haploidentical HSCT with post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) may predispose to atypical endothelial injuries, including delayed-onset VOD, possibly due to delayed clearance of cyclophosphamide metabolites or cumulative vascular injury from preceding infections or nephrotoxic drugs.[2,3] This further expands the spectrum of patients in whom we must consider late-onset SOS, especially when clinical progress diverges from expectation.

|

Table 1. Timeline of Events. |

|

Table 2. Investigations Summary. |

Conclusion

Late-onset VOD is an underrecognized and often delayed diagnosis due to its atypical and subtle clinical presentation. Unlike classical VOD, late-onset cases may lack hallmark features such as jaundice and painful hepatomegaly, as seen in our patient who initially had normal liver enzymes and anicteric ascites. This variability can lead to missed or delayed diagnosis, which may adversely impact outcomes if appropriate therapy, such as defibrotide, is not initiated promptly.In cases of persistent or unexplained hepatomegaly, ascites, and signs of portal hypertension after HSCT — especially beyond day +21 — clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for late-onset VOD, even in the absence of typical laboratory abnormalities. In such settings, liver biopsy becomes an invaluable diagnostic tool to establish the diagnosis and guide management.

Our case underscores the importance of early recognition of late-onset VOD and consideration of biopsy when clinical suspicion remains high. Timely diagnosis enables the provision of appropriate supportive care and the potential initiation of disease-modifying therapy, thereby improving the chances of recovery. Fortunately, our patient responded well to conservative measures with resolution of hyperbilirubinemia and renal dysfunction and remains under close outpatient follow-up. This case adds to the growing awareness that late-onset VOD, while rare, is an important and potentially reversible cause of post-transplant morbidity when identified and managed appropriately.

Data availability statement

Due to patient privacy and institutional policies, the data supporting the findings of this article are not publicly available. Requests for access to the data may be directed to the corresponding author.Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.References

- Dalle JH, Giralt SA. Hepatic Veno-Occlusive Disease

after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Risk Factors and

Stratification, Prophylaxis, and Treatment. Biol Blood Marrow

Transplant. 2016;22(3):400-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.024 PMid:26431626

- Castellino

A, Guidi S, Dellacasa CM, Gozzini A, Donnini I, Nozzoli C, et al.

Late-Onset Hepatic Veno-Occlusive Disease after Allografting: Report of

Two Cases with Atypical Clinical Features Successfully Treated with

Defibrotide. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2018;10(1):e2018001. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2018.001 PMid:29326798 PMCid:PMC5760078

- Corbacioglu

S, Jabbour EJ, Mohty M. Risk Factors for Development of and Progression

of Hepatic Veno-Occlusive Disease/Sinusoidal Obstruction Syndrome. Biol

Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(7):1271-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.02.018 PMid:30797942

- Coppell

JA, Richardson PG, Soiffer R, Martin PL, Kernan NA, Chen A, et al.

Hepatic veno-occlusive disease following stem cell transplantation:

incidence, clinical course, and outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant.

2010;16(2):157-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.024 PMid:19766729 PMCid:PMC3018714

- Corbacioglu

S, Carreras E, Ansari M, Balduzzi A, Cesaro S, Dalle JH, et al.

Diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction

syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in pediatric patients: a new

classification from the European Society for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(6):931-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2017.161 PMid:28759025 PMCid:PMC5803572

- Fan CQ, Crawford JM. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (hepatic veno-occlusive disease). J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(4):332-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2014.10.002 PMid:25755580 PMCid:PMC4298625

- Richardson

PG, Smith AR, Bleakley M, Blazar BR, Schuening FG, Parikh S, et al.

Defibrotide for the treatment of hepatic veno-occlusive disease. Biol

Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(2):199-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.017

- Paul

G. Richardson, Marcie L. Riches, Nancy A. Kernan, et al; Phase 3 trial

of defibrotide for the treatment of severe veno-occlusive disease and

multi-organ failure. Blood 2016; 127 (13): 1656-1665. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-10-676924 PMid:26825712 PMCid:PMC4817309

- Mohty

M, Malard F, Abecasis M, Aerts E, Alaskar AS, et al. Prophylactic,

preemptive, and curative treatment for sinusoidal obstruction

syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a position statement

from an international expert group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020

Mar;55(3):485-495. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0705-z PMid:31576023 PMCid:PMC7051913

- Ruggiu M, Bedossa P, Rautou PE, Bertheau P, Plessier A, de Latour RP, et al. Utility and safety of liver biopsy in patients with undetermined liver blood test anomalies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a monocentric retrospective cohort study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(12):2523-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.07.037 PMid:30071321