The present study utilized a contemporary adult SCD cohort in steady state with the aim of providing insights into the patient-reported impact of SCD on QoL. It provided an opportunity to examine the relationship between social-demographic, clinical, and biological events and patient-reported QoL. In the absence of fully validated SCD-specific questionnaires, most QoL studies have relied on standardized, generic HRQoL assessments. Our main goals were to compare such a scoring assessment with a more specific scoring system and to advance our understanding of factors that are important to improve QoL and function of patients with SCD.

Patients and Methods

Patients. All adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) with SCD (established by hemoglobin electrophoresis, confirmed by genetic analysis when diagnosis was unclear) followed at the Constitutive Reference Center of our University Hospital for major SCDs, seen in steady phase at a routine clinic visit from April 2023 to May 2024, were systematically invited to participate in this prospective study. Overall, 240 successive patients entered the study. All participants were informed about the aims of the study and gave non-opposition consent to anonymous data collection and analyses. The study was approved by an institutional scientific committee (MR004, RNIPH 25-5126) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the Declaration of Helsinki. Four patients (1.6%) did not return the questionnaire or failed to complete it. Therefore, 236 patients were analyzed. Steady state was defined as free of clinical complications, including vaso-occlusive complications or any acute exacerbations, at the time of consultation.[14] People with sickle cell trait (AS) were excluded. Analyzed patients had baseline data on their disease characteristics abstracted from their medical records. Demographic characteristics included: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and employment. Clinical characteristics included: antecedents of serious SCD events (VOC, ACS, organopathies), current treatments, SCD-related complications since last consultation (6 months), and interval of time from last acute SCD complication requiring hospitalization to the present consultation. Biological parameters included SCD genotype (SS, SC, Sβ0, Sβ+, others), hemoglobin (Hb) level, mean corpuscular volume (CVM), ferritin and vitamin D levels, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) count, and HbF percentage for patients treated with HU. BMI was calculated as weight (Kg)/height2 (m2) and categorized as underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5-25), overweight (>25-30), and obese (>30). Anemia was defined as moderate with Hb level between 100 g/L and 70 g/L, and severe with Hb level less than 70 g/L.[15] Patients were stratified as either on HU (defined as having received HU for a minimum of 3 months), chronic transfusion therapy (receiving current monthly exchange or simple transfusions ongoing for a minimum of 6 months), other SCD-specific treatments, or treatment naïve (not on any SCD-specific modifying therapy). Good compliance with HU therapy was arbitrarily defined by HbF > 15% at the time of consultation.QoL measurement. Two questionnaires were given simultaneously for QoL measurement: (i) the 36-item short-form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire, developed by RAND Health, a universally accepted tool for assessing HRQoL of many chronic diseases; and (ii) the sickle cell self-efficacy scale (SCSES), considered as a tailored disease-specific questionnaire.

Short-form health survey SF-36 (RAND 36-item). The SF-36 version 2.0 (RAND 36-item) is a non-disease-specific measure of HRQoL. The RAND 36-item, adapted to the pace of consultations, comprises 36 items with eight subscales: physical functioning (10 items), physical role functions (4 items), bodily pain (2 items), and general health (5 items) which construct the physical component summary (PCS), and emotional role functioning (3 items), vitality (4 items), mental health (5 items), and social functioning (2 items) which construct the mental component summary (MCS).[16-18] PCS and MCS scores were calculated as means of their own subscales. Furthermore, one item scores the patient's health estimation compared to his health status one year ago, ranging from “much worse” to “much better”. Scores of the various parts of the questionnaire are transformed into the range of 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate better QoL, and lower scores indicate poor QoL.

Sickle cell self-efficacy scale (SCSES). The SCSES comprises 9 items that ask the respondents to rate their confidence in their ability to manage their SCD, control SCD-related pain, engage in activities of daily living while living with SCD, and manage emotions/frustrations related to living with SCD.[3] The patients’ responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not sure at all”) to 5 (“completely sure”). The overall score of the scale varies from 9 to 45, and a higher score indicates better SE. The score of the scale is categorized into three levels: low SE (9 – 20.99), moderate SE (21 – 32.99), and high SE (33 – 45).

Statistical analysis. All evaluation parameters were subjected to a descriptive analysis. The quantitative variable evaluation parameters were described using position parameters (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation (SD), inter-quartile range (IQR)). The qualitative variable evaluation parameters are shown in the form of numbers and frequency for each modality. Independent t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare the mean score of the PCS, the MCS, and the SCSES in terms of dichotomous demographic, clinical, and therapeutic variables. Differences among categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test.

Regarding continuous variables, the threshold chosen for the analyses was often the median value. In this setting, median PCS and MCS scores were used as cut-offs to individualize higher and lower scores. The significant variables, in addition to PCS and MCS scores, were entered into a regression model as independent variables. Independent determinants of HRQoL were established using multivariate regression models. Estimated hazard ratios (HRs) are reported as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The statistical significance cut-off was set at a p-value < 0.05. All computations were run using the BMDP statistical Software (BMDP Statistical Software, Los Angeles, CA).

Results

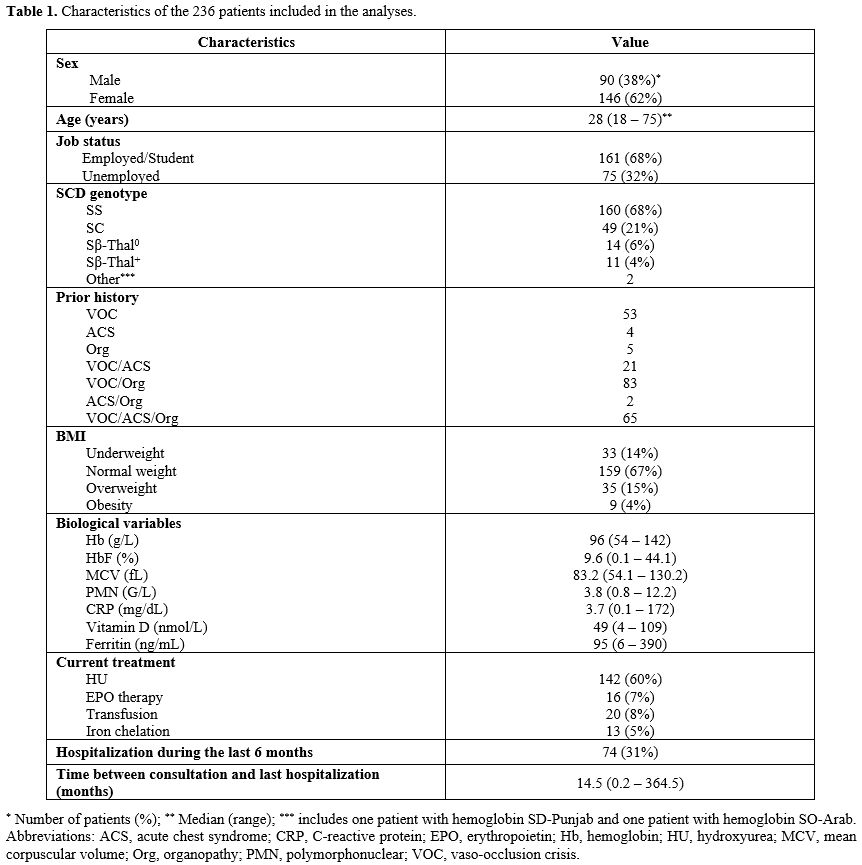

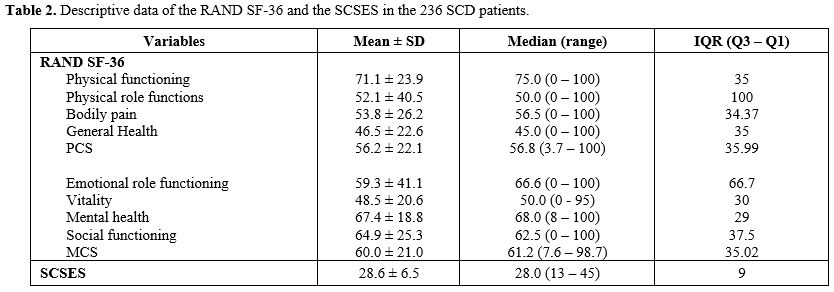

Social-demographic, biological, and clinical characteristics of patients. A total of 240 participants with SCD entered the study. Of the enrolled patients, 236 individuals completed the questionnaire and were analyzed. Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics and an overview of the disease and treatment characteristics of the analyzed cohort. The median age was 28 years (range: 18 – 75 years). The cohort included 160 SCD patients with genotype SS (68%), 49 with genotype SC (21%), 14 with Sβ0 thalassemia (6%), 11 with Sβ+ thalassemia (4%), and 2 with others (1%). Main clinical and biological features at the time of QoL evaluation are indicated in Table 1. Most patients had experienced more than one SCD-related complication and more than one affected organ system. The prior occurrence of acute VOC was the most common complication (94%), followed by organopathies (66%) and ACS (39%). Among organopathies, gall bladder disease was the most frequent (33%), followed by bone complications (19%), vascular complications (12%), retinopathy (14%), and renal complications (5%). Eleven percent of patients had a prior splenectomy. Seventy-four patients (31%) experienced one hospitalization for SCD complication during the last 6 months. All 74 patients presented VOC complicated by ACS in one case or organopathy in 3 cases. Regarding therapy at the time of consultation, 60% of participants (142 patients) were taking HU. Twenty patients (8%) followed a transfusion program, 16 (7%) received erythropoietin (EPO), and 13 (5%) received iron chelating therapy. Twenty-three patients (9%) participated in investigational trials testing novel agents, including endari (L-glutamine), pyruvate kinase activators, voxelotor, or crizanlizumab.Health-related quality of life of the patients. Table 2 shows the median and mean scores and IQR of the 236 patients according to SCSES and RAND SF-36 with its various domains of HRQoL. With the SCSES, 29 patients were classified as low SE (12%), 133 as moderate SE (56%), and 71 as high SE (30%). Three patients did not fill out the SCSES questionnaire. Regarding the RAND SF-36 variables, the lowest scores were in energy/fatigue (mean 48.5 ± 20.6 SD) and general health (46.5 ± 22.6), followed by pain (53.6 ± 26.2). The highest score was in physical functioning (71.1 ± 23.9). Overall, the mean MCS score was 60.0 ± 21.0, and the mean PCS score was 56.2 ± 22.1.

Participants evaluated their current health status compared to the previous year. Forty-eight subjects (20%) rated their general health as somewhat worse or much worse than the previous year, while 90 (38%) indicated that health status did not change, and 98 (42%) that it was better or much better.

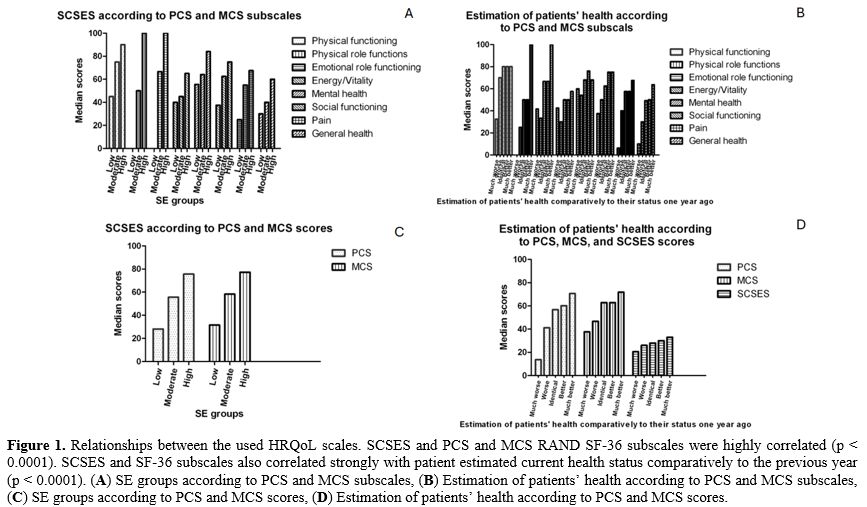

Relationships between the used HRQoL scales, SCSES, PCS, and MCS RAND SF-36 subscales were highly correlated (p < 0.0001). SCSES and SF-36 subscales also correlated strongly with patients' estimated current health status compared to the previous year (p < 0.0001) (Figure 1 A-D).

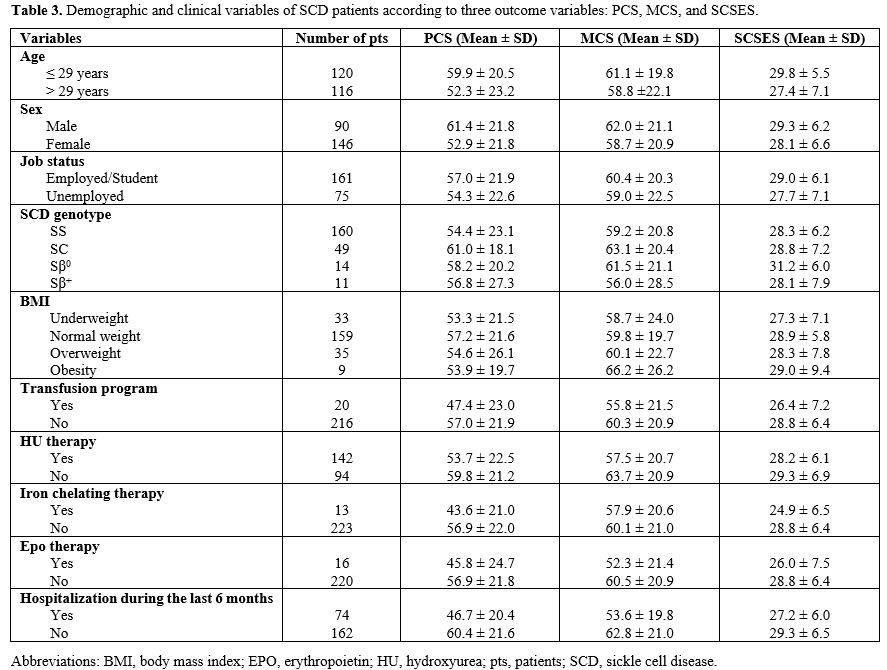

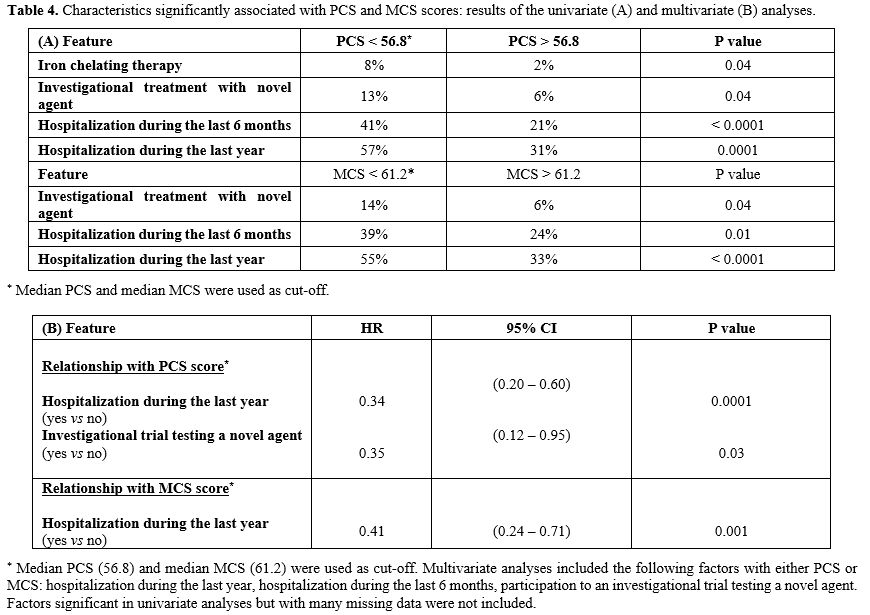

Associations between patient-reported QoL and demographic, disease, and treatment characteristics. Demographic and clinical variables of SCD patients according to PCS, MCS, and SCSES were detailed in Table 3. In univariate analyses, iron chelating therapy was associated with lower PCS scores (p = 0.04), and MCV < 100 fL with lower MCS scores (p = 0.01). Treatment with a novel agent was correlated with both lower PCS and MCS (p = 0.04). In addition, Hospitalizations for SCD complications during the last 6 months and the last year before consultation were significantly associated with lower PCS (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0001, respectively) and MCS (p = 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively) scores. Results are detailed in Table 4A.

Multiple regressions were performed to examine the relationship between SCD-specific variables and PCS and MCS SF-36 scores. Table 4B presents the findings from multivariate analysis. Hospitalization during the last year remained the main feature significantly associated with PCS (p = 0.0001) and MCS (p = 0.001) scores.

|

Table 3. Demographic and clinical variables of SCD patients according to three outcome variables: PCS, MCS, and SCSES. |

|

Table 4. Characteristics significantly associated with PCS and MCS scores: results of the univariate (A) and multivariate (B) analyses. |

Impact of HU therapy on patient-reported QoL. One hundred and forty-two patients received HU at the time of the consultation. Median dose was 18 mg/Kg/day and median time of administration was 71.9 months (range: 3.1 – 382.4 months). In this patient subset, SCSES remained strongly correlated to PCS and MCS RAND SF-36 subscales (p = 0.001 and p = 0.01, respectively). Both SCSES and SF-36 subscales also correlated strongly with patients' estimated current health status compared to the previous year (p = 0.03, p = 0.01, and p = 0.001, respectively). Demographic, therapeutic, and clinical variables associated with PCS and MCS scores were similar in the HU-treated population as in the general patient population.

When considering patients with good compliance to HU therapy defined by HbF > 15%, a significant association was demonstrated with the higher SE group (p = 0.04), and with higher emotional role functioning scores (p = 0.03) of the RAND SF-36. Patients displaying a good compliance to HU therapy were also associated with higher Hb level > 100 g/L (31% vs 13%; p = 0.04), MCV > 100 fL (60% vs 7%; p < 0.0001), and ferritin > 95 ng/mL (89% vs 45%; p < 0.0001).

Discussion

With advances in treatment for SCD, the life expectancy has significantly increased in high-income countries over the last decades, leading to an increased prevalence of mature adults who should deal with repeated SCD complications that may seriously affect their QoL. Although QoL evaluation is a cornerstone in hematological diseases, it is rarely considered as such and is often seen as a secondary endpoint. However, a better understanding of patient experience and their QoL, especially under treatment, is essential in promoting health and well-being. In this setting, all therapeutic approaches should answer two major questions: “How long can I live without any severe complication of my disease?” and “with what impact on my QoL?”Available data from the patient viewpoint regarding the SCD impact on QoL remains relatively limited. Most of them have relied on standardized, generic HRQoL assessments, such as the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36).[19-21] These studies have shown that SCD patients still experience very poor HRQoL. However, these generic scales are questionable. They do not consider SCD-specific symptoms and are not comprehensive assessments of all aspects of patients’ lives. They may therefore underestimate the burden of illness of SCD. In our study, we first compared the unspecific SF-36 scoring system with the more specific SCSES score. Although this last one questioned more disease-specific points, it also has imperfections and did not explore the physical and mental components of QoL as deeply. Despite these imperfections, the good correlation observed among the two scoring systems strengthened the value of each questionnaire and tended to validate previous published data using the SCD-unspecific scoring system.

Previous studies found that pain impairs health status and QoL more than any other SCD-related complication.[19,22] They reported that SCD did not have negative effects on the emotional and social well-being of the patients,[12,21,22] suggesting a patient adaptation to their chronic disease with a tendency to focus more on the positive experience of the disease.[21] Strong religious beliefs in African populations have been put forward to partly explain this fact.[20] It has also been shown that access to good healthcare services improves the QoL by reducing the frequency of bone pain crises, suggesting that more effective management of persistent pain could improve the QoL. The level of income has also been shown as an independent determinant of QoL.[21,23]

Our findings identified several disease and treatment characteristics that were significantly associated with QoL. In contrast with previous reports,[12,21,22] the main factor associated with patient QoL in our series was directly dependent on the expression of the patient's chronic disease requiring a recent hospitalization for severe SCD complications. Certainly, hospitalization was always associated with VOC and, therefore, pain, but pain was not the primary reason for patient complaints. While SCD genotype is often considered a main determinant of disease severity, SCD genotype was not associated in our study with any HRQoL subscales, which was partly consistent with previous findings. In other studies, HRQoL was not associated with genotype except for the vitality subscale.[12] However, the direction of the statistically significant association between vitality for SS/Sβ0 thal vs SC/Sβ+ thal was opposite of what would have been expected, with the more severe genotypes being associated with better vitality, suggesting that patients with severe genotypes tended to be more compliant with hospital visits and treatment. Of note, a recent large study reported that the SC genotype was more clinically severe than previously recognized.[24,25] An unexpected finding in our study was the association between lower PCS and MCS scores and patient participation in investigational trials testing novel agents. This relationship with lower scores cannot be explained by potential treatment side effects, given the heterogeneity of tested molecules. It was more likely due to patient apprehension, fears, and anxiety caused by the administration of unknown molecules. Treatments in this patient population are often subject to reluctance, leading to poor compliance with therapy. This reluctance was also seen with a classic treatment such as HU therapy. Indeed, only 41% of patients from our series achieved correct percentages of HbF, signifying good compliance with treatment, generally confirmed by a good correlation with higher MCV values, while all were supposed to receive a regular dose of HU. Good observance of HU doses was associated with higher SE scores and with higher emotional role functioning scores, suggesting less anxiety and depressive tendencies. Previous studies showed better physical functioning in adults with SCD who were taking HU compared to those who were not.[26,27] HU significantly improves pain outcomes, reduces the occurrence of SCD complications, decreases healthcare costs, and improves HRQoL.[28-31]

Despite interesting findings, a number of limitations should be noted in our study. Subject selection could have been biased toward less symptomatic individuals as recruitment was targeted to stable individuals seen in programmed consultation or day care unit hospitalization for regular health check, while the questionnaire was not proposed at the time of hospitalization for any SCD complications. Some important factors were not assessed, such as measurement of protein-energy intake and micronutrient levels, the deficiency of which was shown to increase SCD severity and hospitalizations, and to reduce HRQoL.[32] Furthermore, some studied subpopulations were too small to allow accurate statistical analyses and should only be interpreted with caution. HU compliance was arbitrarily defined and voluntary, quite simplistic. It may be affected by inter-individual variability. A more complex and likely more accurate definition of HU compliance involving additional factors to HbF was not selected because it would lead to too small subgroups. Although not representing many patients (4 patients), another potential bias was the need for the subjects included to be able to understand and answer the questionnaire, excluding therefore patients not fluent in the French language.

Conclusions

Overall, our study confirmed the utility of the QoL questionnaire, whatever it was, to estimate the physical and mental components of patients with SCD. QoL in patients, although in steady state, remained relatively poor, with median PCS and MCS only around 60% and median SCSES score in the moderate group. Fatigue and pain remained the most affected subscales. Negative points were related to chronic manifestations of the disease: recent hospitalizations impacted HRQoL severely, as also did chronic features associated with severe anemia. The most important point was the favorable impact of HU therapy on QoL when correctly taken. This encourages us to monitor HU therapy more closely and to encourage patients to comply with their treatment. Our study suggests that a more effective management of the disease, notably in terms of compliance with the prescribed therapy, could substantially improve the QoL for adults with SCD. Validation on a larger prospective series is warranted.Author contributions

Giovanna Cannas contributed to the study conception and design, performed statistical analyses, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. Giovanna Cannas, Solène Poutrel, Emilie Virot, Manon Marie, Alexandre Guilhem, and Amal El-Kanouni took care of patients. Richard Bourgeay provided technical support. Marie-Grace Mutumwa and Mohamed Elhamri performed data collection. Arnaud Hot critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.References

- Piel FB, Steinberg MH,

Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:1561-73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1510865

PMid:28423290

- Bulgin

D, Tanabe P, Jenerette C. Stigma of sickle cell disease: a systematic

review. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018; 39:675-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1443530

PMid:29652215 PMCid:PMC6186193

- Edwards

R, Telfair J, Cecil H, Lenoci J. Reliability and validity of a

self-efficacy instrument specific to sickle cell disease. Behav Res

Ther. 2000; 38:951-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00140-0

PMid:10957829

- Molter

BL, Abrahamson K. Self-efficacy, transition, and patient outcomes in

the sickle cell disease population. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015; 16:418-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2014.06.001

PMid:25047808

- Barlett

R, Ramsay Z, Ali A, Grant J, Rankine-Mullings A, Gordon-Strachan G,

Asnani M. Health-related quality of life and neuropathic pain in sickle

cell disease in Jamaica. Disability and Health Journal. 2021;

14:101107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101107

PMid:33867318

- Al

Nagshabandi EA, Abdulmutalib IAM. Self-care management and

self-efficacy among ault patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Nurs

Res. 2019; 7:51-7.

- Osunkwo

I, Andemariam B, Minniti CP, Inusa BPD, El Rassi F, Francis-Gibson B,

Nero A, Trimnell C, Abboud MR, Arlet JB, Colombatti R, de Montalembert

M, Jain S, Jastaniah W, Nur E, Pita M, DeBonnett L, Ramscar N, Bailey

T, Rajkovic-Hooley O, James J. Impact of sickle cell disease on

patients' daily lives, symptoms reported, and disease management

strategies: results from the international Sickle Cell World Assessment

Survey (SWAY). Am J Hematol. 2021; 96:404-417. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26063

PMid:33264445 PMCid:PMC8248107

- Drahos

J, Boateng-Kuffour A, Calvert M, Valentine A, Mason A, Li N, Pakbaz Z,

Shah F, Martin AP. Qualitative assessment of health-related quality of

life impacts associated with sickle cell disease in the United States

and United Kingdom. Adv Ther. 2025; 42:863-885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-03038-x

PMid:39680309 PMCid:PMC11787150

- Seth

T, Udupi S, Jain S, Bhatwadekar S, Menon N, Kumar Jena R, Kumar R, Ray

S, Parmar B, Kumar Goel A, Vasava A, Dutta A, Samal P, Ballikar R, Bhat

D, Kanti Dolai T, Bhattacharyya J, Shetty D, Mistry M, Jain D. Burden

of vaso-occlusive crisis, its management and impact on quality of life

of Indian sickle cell disease patients. Br J Haematol. 2025;

206:296-309. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.19829

PMid:39463175 PMCid:PMC11739767

- Barakat

LP, Patterson CA, Daniel LC, Dampier C. Quality of life among

adolescents with sickle cell disease: mediation of pain by

internalizing symptoms and parenting stress. Health Qual Life Outcomes.

2008; 6:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-60

PMid:18691422 PMCid:PMC2526071

- Brandow

AM, Brousseau DC, Pajewski NM, Panepinto JA. Vaso-occlusive painful

events in sickle cell disease: impact on child well-being. Pediatr

Blood Cancer. 2010; 54: 92-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22222

PMid:19653296 PMCid:PMC3114448

- McClish

DK, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, Roberts JD, Aisiku IP, Levenson JL,

Roseff SD, Smith WR. Health related quality of life in sickle cell

patients: the PiSCES project. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005; 3:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-3-50

PMid:16129027 PMCid:PMC1253526

- Panepinto

JA, O'Mahar KM, DeBaun MR, Loberiza FR, Scott JP. Health-related

quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: child and parent

perception. Br J Haematol. 2005; 130:437-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05622.x

PMid:16042695

- Ballas

SK. More definitions in sickle cell disease: steady state v base line

data. Am J Hematol. 2012; 87:228. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.22259

PMid:22190068

- World

Health Organization. Guideline on haemoglobin cut-offs to define

anaemia in individuals and populations. World Health Organization 2024.

ISBN: 978-92-4-008854-2.

- Ware

JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36):

I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;

30:473-83. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

PMid:1593914

- Montazeri

A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The short form health survey

(SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual

Life Res. 2005; 14:875-82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5

PMid:16022079

- Van

der Zee KI, Sanderman R, Heyink J. A comparison of two multidimensional

measures of health status: the Nottingham Health Profile and the RAND

36-item health survey 1.0. Qual Life Res. 1996; 5:165-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00435982

PMid:8901380

- Dampier

C, LeBeau P, Rhee S, Lieff S, Kesler K, Ballas S, Rogers Z, Wang W.

Health-related quality of life in adults with sickle cell disease

(SCD): a report from the comprehensive sickle cell centers clinical

trial consortium. Am J Hematol. 2011; 86:203-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21905

PMid:21264908 PMCid:PMC3554393

- Anie

KA, Dasgupta T, Ezenduka P, Anarado A, Emodi I. A cross-cultural study

of psychosocial aspects of sickle cell disease in the UK and Nigeria.

Psychol Health Med. 2007; 12:299-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600984034

PMid:17510899

- Adeyemo

TA, Ojewunmi OO, Diaku-Akinwumi IN, Ayinde OC, Akanmu AS. Health

related quality of life and perception of stigmatization in adolescents

living with sickle cell disease in Nigeria: a cross sectional study.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015; 62:1245-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25503

PMid:25810358

- Amaeshi

L, Kalejaiye OO, Ogamba CF, Popoola FA, Adelabu YA, Ikwuegbuenyi CA,

Nwankwo IB, Adeniran O, Imeh M, Kehinde MO. Health-related quality of

life among patients with sickle cell disease in an adult hematology

clinic in a tertiary hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Cureus. 2022;

14:e21377. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21377

PMid:35198289 PMCid:PMC8854203

- Okany

CC, Akinyanju, OO. The influence of socioeconomic status on the

severity of sickle cell disease. Afr J Med Sci. 1993; 22:57-60.

- Nelson

M, Noisette L, Pugh N, Gordeuk V, Hsu LL, Wun T, Shah N, Glassberg J,

Kutlar A, Hankins JS, King AA, Brambilla D, Kanter J. The clinical

spectrum of HbSC sickle cell disease-not a benign condition. Br J

Haematol. 2024; 205:653-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.19523

PMid:38898714 PMCid:PMC11315634

- Segbefia

C, Luchtman-Jones L. Seeing haemoglobin SC: challenging the

misperceptions. Br J Haematol. 2024; 205:404-5. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.19580

PMid:38922871

- Ballas

SK, Barton FB, Waclawiw MA, Swerdlow P, Eckman JR, Pegelow CH, Koshy M,

Barton BA, Bonds DR. Hydroxyurea and sickle cell anemia: effect on

quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006; 4:59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-59

PMid:16942629 PMCid:PMC1569824

- Kelly

MJ, Pennarola BW, Rodday AM, Parsons SK. Health-related quality of life

(HRQOL) in children with sickle cell disease and thalassemia following

hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;

59:725-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24036

PMid:22183952 PMCid:PMC3319491

- Badawy

SM, Thompson AA, Lai J, Penedo FJ, Rychlik K, Liem RI. Adherence to

hydroxyurea, health-related quality of life domains, and patients'

perceptions of sickle cell disease and hydroxyurea: a cross-sectional

study in adolescents and young adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;

15:136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0713-x

PMid:28679417 PMCid:PMC5498866

- Nevitt

SJ, Jones AP, Howard J. Hydroxyurea (hydroxycarbamine) for sickle cell

disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; 4:CD002202. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002202.pub2

PMid:28426137

- Moore

RD, Charache S, Terrin ML, Barton FB, Ballas SK. Cost-effectiveness of

hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter

Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. Am J Hematol. 2000;

64:26-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(200005)64:1<26::AID-AJH5>3.0.CO;2-F

- Yang

M, Elmuti L, Badawy SM. Health-related quality of life and adherence to

hydroxyurea and other disease-modifying therapies among individuals

with sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2022;

2022:2122056. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2122056

PMid:35898672 PMCid:PMC9313963

- Kamal

S, Naghib MM, Al Zahrani J, Hassan H, Moawad K, Arrahman O. Influence

of nutrition on disease severity and health-related quality of life in

adults with sickle cell disease: a prospective study. Mediterr J

Hematol Infect Dis 2021; 13: e2021007. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2021.007

PMid:33489046 PMCid:PMC781327