In recent years, the number of transplant procedures and the median age of HCT patients have increased, and both transplant-related complications and infections are more frequent.[9] On the other hand, the incidence of IFI has changed significantly over the years, also due to the introduction of new drugs used in the field of prophylaxis and treatment.[4]

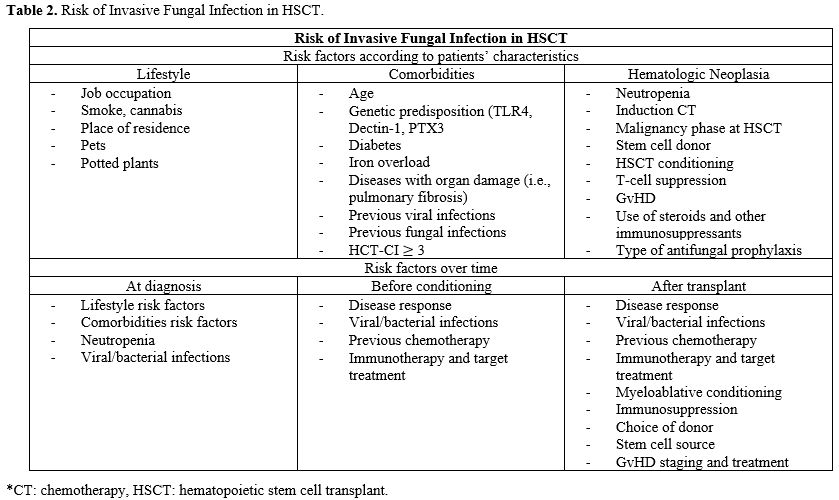

Considering the poor outcomes associated with infections due to IFIs in immunocompromised hosts, it is essential to identify risk factors that increase the likelihood of IFI development after allogeneic transplantation.[10] In particular, it is important to distinguish risk factors related to the patient's lifestyle, those connected to the patient's hematological disease and its specific treatment, and finally those depending on the characteristics of HCT itself, such as the type of donor, stem cell source, conditioning, and GvHD (graft versus host disease) prophylaxis.[4,11,12]

To reduce the incidence of IFIs, an appropriate prophylaxis plays a crucial role: recently, ECIL (European Conference on Infections in Leukemia), ESCMID (European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases), and IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical guidelines) have updated indications on the most effective prophylaxis in immunosuppressed patients.[13-15] In particular, for allo-HCT patients, it is crucial to distinguish between the pre-engraftment and post-engraftment periods, as they present different risk factors for IFIs.[13,14,16]

Regarding indications for treatment, different classes of drugs are available, with specific pharmacological interactions and side effects. Sixteen new compounds are also undergoing clinical trials to expand therapeutic possibilities for these patients.[17]

Our review aims to provide useful tools for risk stratification, primary prophylaxis, and therapeutic management of IFIs in HCT recipients.

Epidemiology

Over the last decade, the epidemiology of IFIs has undergone dramatic changes, largely due to the increasing number of immunosuppressive treatments, the use of invasive devices, and a higher volume of transplant procedures.[18]Invasive candidiasis is the most common fungal disease among hospitalized patients in the world, with an incidence of 1-14 cases per 100.000 inhabitants[19] and a mortality rate reaching up to 60% in different studies.[20-23] Aspergillosis, on the other hand, affects 1.1-1.8 people per 100.000 inhabitants, with a mortality up to 85% in patients with invasive infections in intensive care settings.[24,25] A recent study on prevalence of fungal infections showed that in 2018, more than 600.000 fungal infections were diagnosed in the United States, with the highest mortality observed in patients diagnosed with mucormycosis (18.6%) and invasive candidiasis (17%), followed by Pneumocystis jirovecii infection (12.9%) and invasive aspergillosis (12.5%).[26]

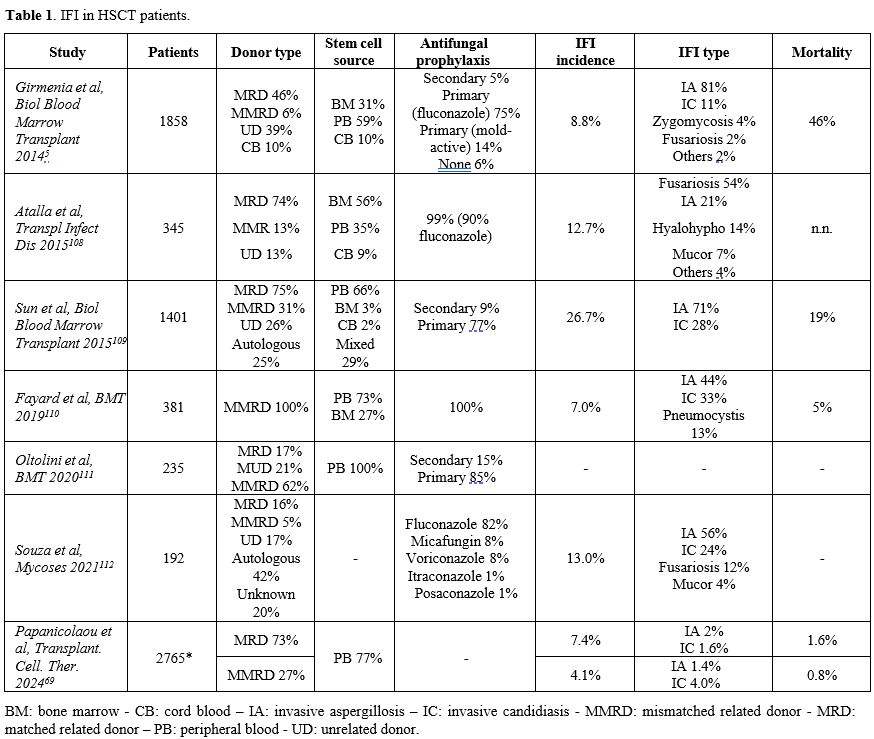

HCT patients are at high risk of IFI as they represent a distinct epidemiological niche for fungal infections. Table 1 describes the reported incidence of IFI in HCT patients, considering stem cell donor type and source, antifungal prophylaxis used, involved pathogens, and mortality.

The incidence of IFI in HCT patients ranges from 7% to 15% across various studies, with a notable shift observed over the last 15 years due to the introduction of new antifungal drugs for both prophylaxis and treatment.[4] In the past, candidemia was one of the most frequent IFIs in hematological patients, with high mortality, up to 60%.[27-29] Non-albicans Candida species were responsible for more than half of Candida infections in HCT, with 33% of infections caused by C. glabrata, 14% by C. parapsilosis, 8% by C. tropicalis, and 6% by C. krusei. Recent studies, however, have shown that the incidence of candidemia is lower than in the past, with a significant reduction in the candidemia fatality rate among HCT patients.[15,31,32] A SEIFEM report published in 2015 compared hematological patients that received HCT (either autologous or allogeneic) in 2011-2015 with a historical cohort (1999-2003).[15] The survey showed an important decrease in candidemia case fatality rate both in patients treated with autologous HCT (44% vs 9.5%, p = 0.01) and in patients who underwent allogeneic HCT (57% vs 24%, p = 0.02).[13-15] Aspergillus is considered the most common invasive mold disease in HCT patients.[4,33,34] Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the most common clinical manifestation, but it can disseminate through vascular invasion to other organs, such as the brain, skin, kidneys, and sinuses.[35] The introduction of antifungal prophylaxis and the use of new and effective anti-mold treatments have changed the epidemiology of Aspergillus infection in HCT, with a prevalence of 43-64% of all IFIs.[36,37] Recent data shows an incidence of IA in allogeneic HCT patients of 8%, with lung localization in 93% of cases and overall mortality reaching 70% in some studies.[35,37,38] The most frequent strains are A. fumigatus (42%), followed by A. niger (26%), A. flavus (11%), and A. terreus (5%).[38] While Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. are responsible for most IFIs in HCT patients, the emergence of non-Aspergillus molds, such as Mucorales (7-8% of cases), Fusarium (0.1-5.2%), Scedosporium, and a few documented cases of Cryptococcus, have been reported.

Risk factors for IFIs

Timely and correct identification of IFI risk factors is critical to improve patients' outcomes. Risk factors for IFIs in HCT candidates should be assessed over time, as they may differ from those initially identified at diagnosis. Transplant conditioning, post-engraftment complications, and prolonged follow-up may all modify the actual risk of IFI. Although risk factors may be already present at the time of the transplant, other less predictable variables may occur during the post-transplant clinical course. As shown in Table 2, three broad categories can be identified, deriving from patient comorbidities and lifestyle, as well as the primary hematologic disease.[11]Among factors related to the patient’s characteristics, the increasing average age of transplant candidates is a crucial consideration. Although no unambiguous threshold value has been identified, some studies have shown that an age of 50 years or older may be associated with an increased risk of IFIs.[42] Comorbidities that increase the risk of IFIs include diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), high BMI, but also iron overload following transfusion dependence.[4,43] Moreover, free iron acts as a catalyst, causing mucositis and negatively influencing the activity of neutrophils, monocytes, NK cells, and macrophages. This mechanism is widely exploited by fungi to proliferate.[4]

Considering the patients’ lifestyle category, a SEIFEM study conducted on 1192 patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) reported a strong correlation between cigarette smoke, cocaine abuse, and invasive mold infections (p = 0.02 and p = 0.006, respectively).[43] Moreover, either having hobbies and jobs involving high exposure to fungal agents or a recent (6 months) house renovation were associated with IFI (p = 0.01, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively).[43]

Risk factors related to the patient's hematologic disease and its treatment define the most variable and dynamic category. Neutropenia, disease response at the time of transplantation (partial vs complete response), previous chemotherapy, immunotherapy and target treatments (including CAR-T therapy), myeloablative conditioning and immunosuppression, choice of donor (haploidentical, mismatched unrelated donors or cord blood transplant) and cell source, occurrence of grade 3-4 GvHD present a specific weight in definition of risk.[4]

Prolonged neutropenia is one of the most significant risk factors for IFI, and it can be detected in more than one-third of HCT patients with a diagnosis of fungal infection.[14,43,44] This data has been confirmed not only during the pre-engraftment phase, but also after engraftment, considering that many infections can be diagnosed months or years after HCT.

Previous viral infections, including respiratory viruses and CMV, as well as the drugs used to treat them, such as ganciclovir, may play a role in favoring IFIs. IFIs have also been described after severe community-acquired viral infections (Influenza, Parainfluenza, and Respiratory syncytial virus) complicated by respiratory failure, with an incidence of IA ranging from 7% to 30%.[45-48] More recently, IA has also been recognized as a significant complication in severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. According to recent data, the incidence of severe aspergillosis after SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia ranges from 2% to 33% of cases, with a mortality of approximately 56%.[49-53] Conversely, the incidence of invasive candidiasis after COVID-19 is 0.8-14%, with a higher risk in ICU settings and a particularly significant mortality rate ranging between 40% and 70%.[54-57]

Regarding chemotherapy, it is essential to consider the destruction of the gut barrier induced by the drugs and their impact on the microbiota. In recent mouse models, the administration of chemotherapy resulted in gut barrier damage, characterized by phenomena of dysbiosis and bacterial translocation.[58] Maintaining the integrity of the intestinal epithelium and the diversity of the microbiota could reduce the risk of IFIs and other complications, including GvHD.[59] Recent data on patients with AML treated with CPX-351 showed a protective effect on mucosal barrier function compared to classic chemotherapy (3+7), with an enhancement of gut microbial activity and antifungal resistance and a more balanced microbial composition thanks to the activation of the pathway of IL-22 and IL-10 and the production of immunomodulatory metabolites by anaerobic bacteria.[59,60]

The use of antifungal prophylaxis during chemotherapy is also a protective factor against IFI, such as the use of posaconazole during acute myeloid leukemia induction treatment.[43]

Patients who undergo allogeneic HCT after CD19-targeted CAR-T therapy are exposed to a magnified infectious risk, with an incidence of IFI as high as 21% in recent studies.[61] Shadman et al described a cohort of 32 patients, with an incidence of IFI of 18% (6/32) and a mortality of 33% (2/6). Target therapies may also increase the risk of developing IFI:[63,64] it is higher with BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib) and with alemtuzumab, moderate/high with PI3K inhibitors (idelalisib, copanlisib, duvelisib), only moderate with blinatumomab and with venetoclax monotherapy.[64-67]

Allogeneic transplantation characteristics are also crucial in risk stratification. In particular, transplantation from an unrelated or haploidentical donor is at higher risk of developing infections than from identical donors.[68-70] In a recent study, the incidence of IFIs in haploidentical donor transplants (haplo-HCT) was 5.2%. In comparison, in sibling identical transplants ranged between 1.9% and 2.2%, with an increased risk of transplant-related mortality and overall mortality.[70] The higher risk of IFIs in these patients could be explained by the increased incidence of GvHD and the slower rate of immune reconstitution after haploidentical transplantation, with a higher incidence of prolonged neutropenia.[71,72] It is also described as an increased number of Candida spp. Infections in cord blood transplantation are likely due to delayed engraftment compared to other donor sources.[73] Infection risk also increases with a second or third transplantation, because failure to engraft after HCT is associated with prolonged cytopenia and a higher toxicity.[69]

Moderate to severe GvHD, referred to as grade 2 or over and requiring treatment with high-dose steroids, increases IFI's risk. In fact, corticosteroids impair the activity of macrophages and neutrophils. However, they also reduce the count of lymphocytes, leading to a deregulation of Th1/Th2.[69] Chronic severe GvHD is also an important risk factor, due to the prolonged immunosuppressive treatment that impacts regulatory immune T and B lymphocytic pathways.[69]

Furthermore, the risk of IFIs tends to lower over the years after transplantation, but it never disappears. In this respect, a study of Foord et al showed that, although infections are less frequent over time, the relative risk remains increased in 5-year HCT survivors versus other cancer survivors and the general population.[74] In particular, bacterial and fungal infections were each 70% more common in HCT versus non-HCT cancer survivors (IRR, 1.7; p = 0.01), with incidences of Aspergillus at 3.3% versus 1.3% and Candida at 4.1% versus 2.8%, respectively.[74]

Antifungal antifungal prophylaxis in allogeneic HCT recipients

Regarding IFI prophylaxis in patients undergoing allogeneic HCT, it is valuable to distinguish between two phases characterized by significantly different risk factors for IFI: the pre-engraftment and post-engraftment phases. During the pre-engraftment period, fluconazole is likely the most valuable choice for antifungal prophylaxis, given its low rate of pharmacological interactions and toxicities. Unfortunately, the moderate efficacy of fluconazole often limits its use.[13,14,75] It is therefore reasonable to prefer fluconazole only in low-risk patients and in hospitals where the epidemiological records show a low risk of mold infection. It is also important to combine the use of fluconazole with a mold-directed diagnostic workup (biomarkers and/or CT scan-based).[13,14,75] On the other hand, using fluconazole in association with other antifungal drugs has not shown any advantages.[13,14]In the post-engraftment period, in high-risk populations and in hospitals with a recurrence of mold infection, posaconazole has been shown to be more effective than fluconazole in preventing IFIs, particularly invasive aspergillosis, with a comparable rate of treatment-related serious adverse events.[76]

Among the azoles, voriconazole is one of the most effective antifungal agents. However, in clinical practice, its administration often presents several challenges in HCT patients, considering the variable pharmacokinetics, the narrow therapeutic window, and drug-to-drug interactions, particularly with immunosuppressive agents.[77,78] One important interaction to consider is with letermovir: voriconazole trough concentrations may decrease after starting letermovir, due to large inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability, which depends on body weight, genetic polymorphism in CYP, liver function, and serum C-reactive protein concentration.[79,80] Although voriconazole serum concentrations may vary during letermovir administration, the incidence of fungal infection does not increase in these patients.

Itraconazole has also shown better protection than fluconazole against invasive mold infections, but with a higher degree of toxicity and lower tolerability.[16,84] On the other hand, isavuconazole has shown conflicting results in terms of efficacy, with variable rates of breakthrough infections (ranging from 3.2 to 17.9%)[84,85] despite an encouraging safety profile.

Regarding echinocandins, evidence in literature mainly concerns micafungin, but comparative studies with fluconazole are often based on a low-risk population, resulting in a low incidence of IFI.[86]

Recent trials are ongoing to explore the efficacy of rezafungin, a new echinocandine derivative of anidulafungin with a safer profile and a longer half-life, approved for the treatment of candidemia.[88]

Antifungal prophylaxis should be continued in GVHD patients with chronic immunosuppression due to steroids (corticosteroid equivalent of > 1 mg/kg/day of prednisone for > 2 weeks) or other anti-GVHD therapies (such as lymphocyte-depleting agents) and in long-term neutropenic patients.

Secondary prophylaxis should also be considered for patients with successfully treated IFI who require subsequent immunosuppression.[14]

IFI treatment

The choice of antifungal treatment should consider various factors, including prior use of mold-active azole prophylaxis, existing comorbidities, the likelihood of azole-resistant Aspergillus infection, and clinical conditions.Voriconazole is the drug of choice for the primary treatment of IA.[13,14] Plasma levels of voriconazole should be controlled 2-5 days after the first dose. If levels are sufficient (between 1-1.5 and 5-6 lg/mL), they should be monitored regularly due to high intraindividual variation.[97] Isavuconazole is an alternative first-line agent with high tolerability and fewer side effects.[98] Regarding posaconazole, data have shown non-inferiority to voriconazole in the treatment of IA, with a limited number of adverse effects.[99]

Treatment should be initiated as soon as possible in patients with strongly suspected IA and continued for at least 6-12 weeks, depending on the degree and duration of immunosuppression, the site of disease, and evidence of disease improvement. We advise against stopping treatment until complete clinical resolution and favorable radiological evolution are achieved. Adjunctive measures should reduce or eliminate immunosuppressive agents when feasible and consider colony-stimulating factors in neutropenic patients with invasive aspergillosis that is refractory or unlikely to respond to standard therapy, and for an expected neutropenia of more than one week. Combining voriconazole and echinocandin may also be considered in selected patients with an incomplete response to first-line therapy and a documented infection.[100] Surgery for aspergillosis should also be considered for localized disease that is accessible to debridement.

Echinocandins, including the new drug rezafungin, are the recommended first-line treatment for candidaemia and all forms of invasive candidiasis, except for neurological and ocular sites, due to their broad activity and safety profile.[101] Second-option treatments include liposomal amphotericin B and fluconazole, although fluconazole resistance must be considered in accordance with local epidemiology.[101]

Cryptococcosis is a rare and lethal infection in HCT patients. Liposomal amphotericin B, 3-4 mg/kg daily, and flucytosine, 25 mg/kg four times a day, are the most effective therapy options for cryptococcal meningitis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and severe isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis in high-income settings.

Recent trials are investigating new drugs for the treatment of IFIs. Opelconazole is an inhibitor of the fungal dihydroorotate dehydrogenase that has shown efficacy against various fungal species, especially A. fumigatus, but also Scedosporium, Lomentospora, Rasamsonia, and Talaromyces.[88] Opelconazole has been designed for topical use and nebulized administration, with a low rate of drug interactions and toxicities and a promising efficacy.[88] Fosmanogepix is an inhibitor of the fungal enzyme Gwt1 with broad-spectrum activity against yeasts including Cryptococcus and Candida, as well as molds, such as azole-resistant Aspergillus.[103,104] Data show that it could be effective against pathogens that usually resist other drugs, such as Scedosporium, Lomentospora prolificans, and Fusarium.[103] It may also have a favorable profile in terms of drug interactions and adverse events.[103]

Ibrexafungerp is a non-competitive inhibitor of the β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase enzyme, demonstrating activity against a range of pathogens, including Candida and Aspergillus spp., while retaining its activity against azole-resistant and echinocandin-resistant strains.[107] Data showed comparable responses to the standard of care in invasive candidiasis, with favorable preliminary results in C. auris infections in terms of efficacy and tolerability, as well as in refractory cases. Mild adverse reactions have been reported, including gastrointestinal symptoms.[107]

Refractory or Progressive Aspergillosis. Aspergillosis can be defined as refractory/progressive when there is a clinical, radiological, or serological worsening in patients who have already started a first-line treatment.[102] A sign of serological refractoriness could be a stable galactomannan (not fallen by either 1 unit or < 0.5 units based on measurements taken at least 7 days apart) after at least 8 days of treatment, or a positive galactomannan from BAL in a patient with a previously negative exam.[102] Other criteria to classify aspergillosis as refractory could include a new, distinct site of infection detected clinically or radiologically, or the progression of the original lesion by> 25% after at least 8 days of therapy.[102]

In case of refractory or rapidly progressive aspergillosis, it is mandatory to exclude the emergence of a different strain. Salvage therapy includes changing the class of antifungals, reducing or reversing the underlying immunosuppression (when feasible), and considering surgery in selected cases. It is also advisable to add another antifungal drug from a different class or combine antifungal treatments from other classes that the patient has not received yet.[97] In documented azole-resistant disease, it is beneficial to switch from voriconazole monotherapy to a combination with an echinocandin or amphotericin B.[96] Not only clinical monitoring, but also serial monitoring of serum galactomannan (at least every 7 days) should be used to monitor disease progression and therapeutic response.

Conclusions

In this review, we highlighted the main challenges of managing invasive fungal infections in HCT patients. In particular, we discussed the main risk factors for IFI and the most influential international guidelines for antifungal prophylaxis and treatment, according to the engraftment phase.Refractory/progressive infections remain a challenge; therefore, combination therapy should be considered, potentially leading to a change in the class of antifungal agents. Reducing the underlying immunosuppression, excluding the emergence of a new pathogen, and surgical debridement are also options, although they are difficult to apply in daily practice.[14]

In the context of new drugs, the possible role of rezafungin as a prophylactic agent in HCT patients will be defined in the next years. Indeed, the data on the use of isavuconazole in the prophylaxis of fungal infections in HCT patients are promising, with good efficacy and an excellent tolerability profile.

Inhaled opelconazole could become very promising: ongoing trials are exploring both monotherapy and combination treatment with other antifungals, exploiting the virtually absent bloodstream absorption and potential for drug interactions. Scientific research on new drugs identified oteseconazole as less toxic than other azoles with a lower risk of drug interactions.

One additional research field is the emergence of rare fungal species, such as Mucorales, for which innovative diagnostic tools and therapeutic options are needed.

Exciting new perspectives concern the role of microbiota. Gut dysbiosis induced by chemotherapy and antibiotics appears to be predisposing for fungal infections, especially by Candida spp. New studies will be needed to determine whether the use of probiotics and prebiotics, in association with antifungal drugs, may play a role in the prophylaxis treatment of IFIs.

Despite significant advances in the treatment of patients undergoing HCT, fungal infections still represent an important cause of morbidity and mortality. Exhaustive knowledge of risk factors associated with the occurrence of IFI has a significant impact on clinical practice, as it enables the identification of patients who require a targeted diagnostic approach, including serial monitoring of radiological and microbiological examinations, such as high-resolution CT scans and bronchoalveolar lavage. Early diagnosis and timely treatment represent available criteria for improving the outcome of these infections and patient survival.

References

- Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, Hadley S,

Kauffman CA, Freifeld A, Anaissie EJ, Brumble LM, Herwaldt L, Ito J,

Kontoyiannis DP, Lyon GM, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Park BJ, Patterson TF,

Perl TM, Oster RA, Schuster MG, Walker R, Walsh TJ, Wannemuehler KA,

Chiller TM. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant

recipients: results of the transplant-associated infection surveillance

network (Transnet). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;50(8). doi:

10.1086/651262. https://doi.org/10.1086/651262 PMid:20218876

- Garcia-Vidal

C, Upton A, Kirby KA, Marr KA. Epidemiology of invasive mold infections

in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: Biological risk factors

for infection according to time after transplantation. Clinical

Infectious Diseases. 2008;47(8). doi:10.1086/591969 https://doi.org/10.1086/591969 PMid:18781877 PMCid:PMC2668264

- Morgan

J, Wannemuehler KA, Marr KA, Hadley S, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ,

Fridkin SK, Pappas PG, Warnock DW. Incidence of invasive aspergillosis

following hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplantation:

Interim results of a prospective multicenter surveillance program. Med

Mycol. 2005;43(SUPPL.1). doi:10.1080/13693780400020113 https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780400020113 PMid:16110792

- Pagano

L, Busca A, Candoni A, Cattaneo C, Cesaro S, Fanci R, Nadali G, Potenza

L, Russo D, Tumbarello M, Nosari A, Aversa F; SEIFEM (Sorveglianza

Epidemiologica Infezioni Fungine nelle Emopatie Maligne) Group.; Other

Authors. Risk stratification for invasive fungal infections in patients

with hematological malignancies: SEIFEM recommendations. Blood Rev.

2017;31(2). doi:10.1016/j.blre.2016.09.002 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2016.09.002 PMid:27682882

- Girmenia

C, Raiola AM, Piciocchi A, Algarotti A, Stanzani M, Cudillo L, Pecoraro

C, Guidi S, Iori AP, Montante B, Chiusolo P, Lanino E, Carella AM,

Zucchetti E, Bruno B, Irrera G, Patriarca F, Baronciani D, Musso M,

Prete A, Risitano AM, Russo D, Mordini N, Pastore D, Vacca A, Onida F,

Falcioni S, Pisapia G, Milone G, Vallisa D, Olivieri A, Bonini A,

Castagnola E, Sica S, Majolino I, Bosi A, Busca A, Arcese W, Bandini G,

Bacigalupo A, Rambaldi A, Locasciulli A. Incidence and outcome of

invasive fungal diseases after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A

prospective study of the gruppo italiano trapianto midollo osseo

(GITMO). Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20(6).

doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.004 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.004 PMid:24631738

- Mikulska

M, Raiola AM, Bruno B, Furfaro E, Van Lint MT, Bregante S, Ibatici A,

Del Bono V, Bacigalupo A, Viscoli C. Risk factors for invasive

aspergillosis and related mortality in recipients of allogeneic SCT

from alternative donors: An analysis of 306 patients. Bone Marrow

Transplant. 2009;44(6). doi:10.1038/bmt.2009.39 https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.39 PMid:19308042

- Kousha

M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: A clinical review.

European Respiratory Review. 2011;20(121).

doi:10.1183/09059180.00001011 https://doi.org/10.1183/09059180.00001011 PMid:21881144 PMCid:PMC9584108

- Denning DW. Invasive Aspergillosis. http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/

- Niederwieser

D, Baldomero H, Bazuaye N, Bupp C, Chaudhri N, Corbacioglu S, Elhaddad

A, Frutos C, Galeano S, Hamad N, Hamidieh AA, Hashmi S, Ho A, Horowitz

MM, Iida M, Jaimovich G, Karduss A, Kodera Y, Kröger N, Péffault de

Latour R, Lee JW, Martínez-Rolón J, Pasquini MC, Passweg J, Paulson K,

Seber A, Snowden JA, Srivastava A, Szer J, Weisdorf D, Worel N, Koh

MBC, Aljurf M, Greinix H, Atsuta Y, Saber W. One and Half Million

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants (HSCT). Dissemination, Trends and

Potential to Improve Activity By Telemedicine from the Worldwide

Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (WBMT). Blood.

2019;134(Supplement_1). doi:10.1182/blood-2019-125232 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-125232

- Xiao

H, Tang Y, Cheng Q, Liu J, Li X. Risk prediction and prognosis of

invasive fungal disease in hematological malignancies patients

complicated with bloodstream infections. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12.

doi:10.2147/CMAR.S238166 https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S238166 PMid:32273756 PMCid:PMC7102877

- Pagano

L, Dragonetti G, Cattaneo C, Marchesi F, Veggia B, Busca A, Candoni A,

Prezioso L, Criscuolo M, Cesaro S, Delia M, Fanci R, Stanzani M,

Ferrari A, Martino B, Melillo L, Nadali G, Simonetti E, Ballanti S,

Picardi M, Castagnola C, Decembrino N, Gazzola M, Fracchiolla NS,

Mancini V, Nosari A, Principe MID, Aversa F, Tumbarello M; SEIFEM group

(Sorveglianza Epidemiologica Infezioni Fungine in Ematologia). Changes

in the incidence of candidemia and related mortality in patients with

hematologic malignancies in the last ten years. A SEIFEM 2015-B report.

Haematologica. 2017;102(10). doi:10.3324/haematol.2017.172536 https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2017.172536 PMid:28729301 PMCid:PMC5622873

- Herbrecht

R, Bories P, Moulin JC, Ledoux MP, Letscher-Bru V. Risk stratification

for invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Ann N Y Acad

Sci. 2012;1272(1). doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06829.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06829.x PMid:23231711

- Patterson

TF, Thompson GR 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R,

Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach

WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. Practice

guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016

update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clinical

Infectious Diseases. 2016;63(4). doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw326 PMid:27365388 PMCid:PMC4967602

- Maertens

JA, Girmenia C, Brüggemann RJ, Duarte RF, Kibbler CC, Ljungman P, Racil

Z, Ribaud P, Slavin MA, Cornely OA, Peter Donnelly J, Cordonnier C;

European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL), a joint venture

of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), the

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), the

Immunocompromised Host Society (ICHS) and; European Conference on

Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL), a joint venture of the European Group

for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), the European Organization

for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), the Immunocompromised

Host Society (ICHS) and the European LeukemiaNet (ELN). European

guidelines for primary antifungal prophylaxis in adult haematology

patients: Summary of the updated recommendations from the European

Conference on Infections in Leukaemia. Journal of Antimicrobial

Chemotherapy. 2018;73(12). doi:10.1093/jac/dky286 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky286

- Ullmann

AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K,

Lass-Flörl C, Lewis RE, Munoz P, Verweij PE, Warris A, Ader F, Akova M,

Arendrup MC, Barnes RA, Beigelman-Aubry C, Blot S, Bouza E, Brüggemann

RJM, Buchheidt D, Cadranel J, Castagnola E, Chakrabarti A,

Cuenca-Estrella M, Dimopoulos G, Fortun J, Gangneux JP, Garbino J,

Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Heussel CP, Kibbler CC, Klimko N, Kullberg BJ,

Lange C, Lehrnbecher T, Löffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti

O, Meis JF, Pagano L, Ribaud P, Richardson M, Roilides E, Ruhnke M,

Sanguinetti M, Sheppard DC, Sinkó J, Skiada A, Vehreschild MJGT,

Viscoli C, Cornely OA. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus

diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline.

Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2018;24.

doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002 PMid:29544767

- Gupta

AK, Versteeg SG, Shear NH. Common drug-drug interactions in antifungal

treatments for superficial fungal infections. Expert Opin Drug Metab

Toxicol. 2018;14(4):387-398. doi:10.1080/17425255.2018.1461834 https://doi.org/10.1080/17425255.2018.1461834 PMid:29633864

- The

Lancet Infectious Diseases. An exciting time for antifungal therapy.

Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(7):763. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00380-8 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00380-8 PMid:37391258

- Enoch

DA, Yang H, Aliyu SH, Micallef C. The changing epidemiology of invasive

fungal infections. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 1508. Humana

Press Inc.; 2017:17-65. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6515-1_2 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6515-1_2 PMid:27837497

- Cleveland

AA, Harrison LH, Farley MM, Hollick R, Stein B, Chiller TM, Lockhart

SR, Park BJ. Declining incidence of candidemia and the shifting

epidemiology of Candida resistance in two US metropolitan areas,

2008-2013: Results from population-based surveillance. PLoS One.

2015;10(3). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120452 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120452 PMid:25822249 PMCid:PMC4378850

- Alp

S, Arikan-Akdagli S, Gulmez D, Ascioglu S, Uzun O, Akova M.

Epidemiology of candidaemia in a tertiary care university hospital:

10-year experience with 381 candidaemia episodes between 2001 and 2010.

Mycoses. 2015;58(8):498-505. doi:10.1111/myc.12349 https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12349 PMid:26155849

- Bassetti

M, Righi E, Ansaldi F, Merelli M, Scarparo C, Antonelli M,

Garnacho-Montero J, Diaz-Martin A, Palacios-Garcia I, Luzzati R, Rosin

C, Lagunes L, Rello J, Almirante B, Scotton PG, Baldin G, Dimopoulos G,

Nucci M, Munoz P, Vena A, Bouza E, de Egea V, Colombo AL, Tascini C,

Menichetti F, Tagliaferri E, Brugnaro P, Sanguinetti M, Mesini A,

Sganga G, Viscoli C, Tumbarello M. A multicenter multinational study of

abdominal candidiasis: epidemiology, outcomes and predictors of

mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(9).

doi:10.1007/s00134-015-3866-2 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3866-2 PMid:26077063

- Caggiano

G, Coretti C, Bartolomeo N, Lovero G, De Giglio O, Montagna MT. Candida

bloodstream infections in Italy: Changing epidemiology during 16 years

of surveillance. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015. doi:10.1155/2015/256580 https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/256580 PMid:26064890 PMCid:PMC4439500

- Bitar

D, Lortholary O, Le Strat Y, Nicolau J, Coignard B, Tattevin P, Che D,

Dromer F. Population-based analysis of invasive fungal infections,

France, 2001-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(7).

doi:10.3201/eid2007.140087 https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2007.140087 PMid:24960557 PMCid:PMC4073874

- Denning

DW. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet

Infect Dis. 2024;24(7). doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00692-8 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00692-8 PMid:38224705

- Baddley

JW, Stephens JM, Ji X, Gao X, Schlamm HT, Tarallo M. Aspergillosis in

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients: Epidemiology and economic outcomes.

BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-29 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-29 PMid:23343366 PMCid:PMC3562254

- Rayens

E, Norris KA. Prevalence and Healthcare Burden of Fungal Infections in

the United States, 2018. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(1).

doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab593 https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofab593 PMid:35036461 PMCid:PMC8754384

- Viscoli

C, Girmenia C, Marinus A, Collette L, Martino P, Vandercam B, Doyen C,

Lebeau B, Spence D, Krcmery V, De Pauw B, Meunier F. Candidemia in

cancer patients: A prospective, multicenter surveillance study by the

invasive fungal infection group (IFIG) of the European organization for

research and treatment of cancer (EORTC). Clinical Infectious Diseases.

1999;28(5). doi:10.1086/514731 https://doi.org/10.1086/514731 PMid:10452637

- Pagano

L, Antinori A, Ammassari A, Mele L, Nosari A, Melillo L, Martino B,

Sanguinetti M, Equitani F, Nobile F, Carotenuto M, Morra E, Morace G,

Leone G. Retrospective study of candidemia in patients with

hematological malignancies. Clinical features, risk factors and outcome

of 76 episodes. Eur J Haematol. 1999 Aug;63(2):77-85. Retrospective

study of candidemia in patients with hematological malignancies.

Clinical features, risk factors and outcome of 76 episodes. Eur J

Haematol. 1999;63(2). doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.1999.tb01120.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.1999.tb01120.x PMid:10480286

- Okinaka

K. Candidemia in cancer patients: Focus mainly on hematological

malignancy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Med Mycol J.

2016;57(3). doi:10.3314/mmj.16.003 https://doi.org/10.3314/mmj.16.003 PMid:27581780

- Kontoyiannis

DP, Marr KA, Park BJ, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Walsh TJ, Ito J, Andes

DR, Baddley JW, Brown JM, Brumble LM, Freifeld AG, Hadley S, Herwaldt

LA, Kauffman CA, Knapp K, Lyon GM, Morrison VA, Papanicolaou G,

Patterson TF, Perl TM, Schuster MG, Walker R, Wannemuehler KA, Wingard

JR, Chiller TM, Pappas PG. Prospective surveillance for invasive fungal

infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2001-2006:

Overview of the transplant- associated infection surveillance network

(TRANSNET) database. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;50(8).

doi:10.1086/651263 https://doi.org/10.1086/651263 PMid:20218877

- Dragonetti

G, Criscuolo M, Fianchi L, Pagano L. Invasive aspergillosis in acute

myeloid leukemia: Are we making progress in reducing mortality? In:

Medical Mycology. Vol 55.; 2017. doi:10.1093/mmy/myw114 https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myw114 PMid:27915304

- Cornely

OA, Gachot B, Akan H, Bassetti M, Uzun O, Kibbler C, Marchetti O, de

Burghgraeve P, Ramadan S, Pylkkanen L, Ameye L, Paesmans M, Donnelly

JP; EORTC Infectious Diseases Group. Epidemiology and outcome of

fungemia in a cancer Cohort of the Infectious Diseases Group (IDG) of

the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC

65031). Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Aug 1;61(3):324-31. doi:

10.1093/cid/civ293. Epub 2015 Apr 13. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2015

Nov 15;61(10):1635. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ820.. Donnelly, Peter J

[corrected to Donnelly, J Peter]. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2022 May

30;74(10):1892. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac144. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac144 PMid:35412606

- Al-Bader

N, Sheppard DC. Aspergillosis and stem cell transplantation: An

overview of experimental pathogenesis studies. Virulence. 2016;7(8).

doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1231278 https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2016.1231278 PMid:27687755 PMCid:PMC5160406

- Steinbach

WJ, Marr KA, Anaissie EJ, Azie N, Quan SP, Meier-Kriesche HU, Apewokin

S, Horn DL. Clinical epidemiology of 960 patients with invasive

aspergillosis from the PATH Alliance registry. Journal of Infection.

2012;65(5). doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2012.08.003 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2012.08.003 PMid:22898389

- Neofytos

D, Horn D, Anaissie E, Steinbach W, Olyaei A, Fishman J, Pfaller M,

Chang C, Webster K, Marr K. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal

infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients:

Analysis of multicenter prospective antifungal therapy (PATH) alliance

registry. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(3). doi:10.1086/595846 https://doi.org/10.1086/595846 PMid:19115967

- Puerta-Alcalde

P, Garcia-Vidal C. Changing epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Fungi.

2021;7(10). doi:10.3390/jof7100848 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7100848 PMid:34682269 PMCid:PMC8539090

- Bays

DJ, Thompson GR. Fungal Infections of the Stem Cell Transplant

Recipient and Hematologic Malignancy Patients. Infect Dis Clin North

Am. 2019;33(2). doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.02.006 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2019.02.006 PMid:31005138

- Upton

A, Kirby KA, Boeckh M, Carpenter PA, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis

following HSCT: Outcomes and prognostic factors associated with

mortality. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12(2).

doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.11.069 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.11.069

- Cerveaux

Y, Brault C, Chouaki T, Maizel J. An uncommon cause of acute hypoxaemic

respiratory failure during haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Ann Hematol. 2019;98(10). doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03753-4 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-019-03753-4 PMid:31278450

- Firacative

C, Carvajal SK, Escandón P, Lizarazo J. Cryptococcosis in Hematopoietic

Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Rare Presentation Warranting

Recognition. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical

Microbiology. 2020;2020. doi:10.1155/2020/3713241 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3713241 PMid:33144899 PMCid:PMC7599392

- Pagano

L, Caira M, Nosari A, Van Lint MT, Candoni A, Offidani M, Aloisi T,

Irrera G, Bonini A, Picardi M, Caramatti C, Invernizzi R, Mattei D,

Melillo L, de Waure C, Reddiconto G, Fianchi L, Valentini CG, Girmenia

C, Leone G, Aversa F. Fungal infections in recipients of hematopoietic

stem cell transplants: Results of the SEIFEM B-2004 study -

Sorveglianza Epidemiologica Infezioni Fungine nelle Emopatie Maligne.

Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45(9). doi:10.1086/522189 https://doi.org/10.1086/522189 PMid:17918077

- Caira

M, Candoni A, Verga L, Busca A, Delia M, Nosari A, Caramatti C,

Castagnola C, Cattaneo C, Fanci R, Chierichini A, Melillo L, Mitra ME,

Picardi M, Potenza L, Salutari P, Vianelli N, Facchini L, Cesarini M,

De Paolis MR, Di Blasi R, Farina F, Venditti A, Ferrari A, Garzia M,

Gasbarrino C, Invernizzi R, Lessi F, Manna A, Martino B, Nadali G,

Offidani M, Paris L, Pavone V, Rossi G, Spadea A, Specchia G,

Trecarichi EM, Vacca A, Cesaro S, Perriello V, Aversa F, Tumbarello M,

Pagano L; SEIFEM Group (Sorveglianza Epidemiologica Infezioni Fungine

in Emopatie Maligne). Pre-Chemotherapy risk factors for invasive fungal

diseases: Prospective analysis of 1,192 patients with newly diagnosed

acute myeloid leukemia (Seifem 2010-a multicenter study).

Haematologica. 2015;100(2). doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.113399 https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2014.113399 PMid:25638805 PMCid:PMC4803126

- Busca

A, Cinatti N, Gill J, Passera R, Dellacasa CM, Giaccone L, Dogliotti I,

Manetta S, Corcione S, De Rosa FG. Management of Invasive Fungal

Infections in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell

Transplantation: The Turin Experience. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

2022;11. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.805514 https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.805514 PMid:35071052 PMCid:PMC8782257

- Di

Stasi A, Milton DR, Poon LM, Hamdi A, Rondon G, Chen J, Pingali SR,

Konopleva M, Kongtim P, Alousi A, Qazilbash MH, Ahmed S, Bashir Q,

Al-atrash G, Oran B, Hosing CM, Kebriaei P, Popat U, Shpall EJ, Lee DA,

de Lima M, Rezvani K, Khouri IF, Champlin RE, Ciurea SO. Similar

transplantation outcomes for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic

syndrome patients with haploidentical versus 10/10 human leukocyte

antigen-matched unrelated and related donors. Biology of Blood and

Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20(12). doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.013 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.013 PMid:25263628 PMCid:PMC4343203

- Schwartz

IS, Friedman DZP, Zapernick L, Dingle TC, Lee N, Sligl W, Zelyas N,

Smith SW. High rates of influenza-associated invasive pulmonary

aspergillosis may not be universal: A retrospective cohort study from

alberta, canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020;71(7).

doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa007 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa007 PMid:31905235

- Schauwvlieghe

AFAD, Rijnders BJA, Philips N, Verwijs R, Vanderbeke L, Van Tienen C,

Lagrou K, Verweij PE, Van de Veerdonk FL, Gommers D, Spronk P, Bergmans

DCJJ, Hoedemaekers A, Andrinopoulou ER, van den Berg CHSB, Juffermans

NP, Hodiamont CJ, Vonk AG, Depuydt P, Boelens J, Wauters J;

Dutch-Belgian Mycosis study group. Invasive aspergillosis in patients

admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: a

retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(10).

doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1 PMid:30076119

- Sarrazyn

C, Dhaese S, Demey B, Vandecasteele S, Reynders M, Van Praet JT.

Incidence, risk factors, timing, and outcome of influenza versus

COVID-19-associated putative invasive aspergillosis. Infect Control

Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(9). doi:10.1017/ice.2020.460 https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.460 PMid:32900411 PMCid:PMC8160496

- Magira

EE, Chemaly RF, Jiang Y, Tarrand J, Kontoyiannis DP. Outcomes in

Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis Infections Complicated by Respiratory

Viral Infections in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: A

Case-Control Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(7).

doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz247 https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz247 PMid:31338382 PMCid:PMC6639596

- Baddley

JW, Thompson GR 3rd, Chen SC, White PL, Johnson MD, Nguyen MH, Schwartz

IS, Spec A, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Jackson BR, Patterson TF, Pappas PG.

Coronavirus Disease 2019-Associated Invasive Fungal Infection. Open

Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(12). doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab510 https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofab510 PMid:34877364 PMCid:PMC8643686

- Permpalung

N, Chiang TP, Massie AB, Zhang SX, Avery RK, Nematollahi S, Ostrander

D, Segev DL, Marr KA. Coronavirus Disease 2019-Associated Pulmonary

Aspergillosis in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Clinical Infectious

Diseases. 2022;74(1). doi:10.1093/cid/ciab223 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab223 PMid:33693551 PMCid:PMC7989534

- Bartoletti

M, Pascale R, Cricca M, Rinaldi M, Maccaro A, Bussini L, Fornaro G,

Tonetti T, Pizzilli G, Francalanci E, Giuntoli L, Rubin A, Moroni A,

Ambretti S, Trapani F, Vatamanu O, Ranieri VM, Castelli A, Baiocchi M,

Lewis R, Giannella M, Viale P; PREDICO Study Group. Epidemiology of

Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis among Intubated Patients with

COVID-19: A Prospective Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases.

2021;73(11). doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1065 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1065 PMid:32719848 PMCid:PMC7454393

- Chauvet

P, Mallat J, Arumadura C, Vangrunderbeek N, Dupre C, Pauquet P, Orfi A,

Granier M, Lemyze M. Risk Factors for Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis

in Critically Ill Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019-Induced Acute

Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(11).

doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000244 https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000244 PMid:33205046 PMCid:PMC7665250

- White

PL, Dhillon R, Cordey A, Hughes H, Faggian F, Soni S, Pandey M,

Whitaker H, May A, Morgan M, Wise MP, Healy B, Blyth I, Price JS, Vale

L, Posso R, Kronda J, Blackwood A, Rafferty H, Moffitt A, Tsitsopoulou

A, Gaur S, Holmes T, Backx M. A National Strategy to Diagnose

Coronavirus Disease 2019-Associated Invasive Fungal Disease in the

Intensive Care Unit. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;73(7).

doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1298 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1298 PMid:32860682 PMCid:PMC7499527

- Antinori

S, Galimberti L, Milazzo L, Ridolfo AL. Bacterial and fungal infections

among patients With SARS-COV-2 pneumonia. Infezioni in Medicina.

2020;28.

- Hughes

S, Troise O, Donaldson H, Mughal N, Moore LSP. Bacterial and fungal

coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective

cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clinical Microbiology and

Infection. 2020;26(10). doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025 PMid:32603803 PMCid:PMC7320692

- Nucci

M, Barreiros G, Guimarães LF, Deriquehem VAS, Castiñeiras AC, Nouér SA.

Increased incidence of candidemia in a tertiary care hospital with the

COVID-19 pandemic. Mycoses. 2021;64(2). doi:10.1111/myc.13225 https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13225 PMid:33275821 PMCid:PMC7753494

- Pemán

J, Ruiz-Gaitán A, García-Vidal C, Salavert M, Ramírez P, Puchades F,

García-Hita M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Quindós G. Fungal coinfection in

COVID-19 patients: Should we be concerned? Rev Iberoam Micol.

2020;37(2). doi:10.1016/j.riam.2020.07.001 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riam.2020.07.001 PMid:33041191 PMCid:PMC7489924

- Hueso

T, Ekpe K, Mayeur C, Gatse A, Joncquel-Chevallier Curt M, Gricourt G,

Rodriguez C, Burdet C, Ulmann G, Neut C, Amini SE, Lepage P, Raynard B,

Willekens C, Micol JB, De Botton S, Yakoub-Agha I, Gottrand F, Desseyn

JL, Thomas M, Woerther PL, Seguy D. Impact and consequences of

intensive chemotherapy on intestinal barrier and microbiota in acute

myeloid leukemia: the role of mucosal strengthening. Gut Microbes.

2020;12(1). doi:10.1080/19490976.2020.1800897 https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2020.1800897 PMid:32893715 PMCid:PMC7524297

- Renga

G, Nunzi E, Stincardini C, Pariano M, Puccetti M, Pieraccini G, Di

Serio C, Fraziano M, Poerio N, Oikonomou V, Mosci P, Garaci E, Fianchi

L, Pagano L, Romani L. CPX-351 exploits the gut microbiota to promote

mucosal barrier function, colonization resistance, and immune

homeostasis. Blood. 2024;143(16). doi:10.1182/blood.2023021380 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023021380 PMid:38227935

- Fianchi

L, Guolo F, Marchesi F, Cattaneo C, Gottardi M, Restuccia F, Candoni A,

Ortu La Barbera E, Fazzi R, Pasciolla C, Finizio O, Fracchiolla N,

Delia M, Lessi F, Dargenio M, Bonuomo V, Del Principe I, Zappasodi P,

Picardi M, Basilico C. Multicenter Observational Retrospective Study on

Febrile Events in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated with

Cpx-351 in "Real-Life": The SEIFEM Experience. Cancers (Basel).

2023;15(13). doi:10.3390/cancers15133457 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15133457 PMid:37444567 PMCid:PMC10341225

- Fried

S, Shouval R, Walji M, Flynn JR, Yerushalmi R, Shem-Tov N, Danylesko I,

Tomas AA, Fein JA, Devlin SM, Sauter CS, Shah GL, Kedmi M, Jacoby E,

Shargian L, Raanani P, Yeshurun M, Perales MA, Nagler A, Avigdor A,

Shimoni A. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation after Chimeric

Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy in Large B Cell Lymphoma. Transplant

Cell Ther. 2023;29(2). doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2022.10.026 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2022.10.026 PMid:36343892 PMCid:PMC10387120

- Shadman

M, Gauthier J, Hay KA, Voutsinas JM, Milano F, Li A, Hirayama AV,

Sorror ML, Cherian S, Chen X, Cassaday RD, Till BG, Gopal AK, Sandmaier

BM, Maloney DG, Turtle CJ. Safety of allogeneic hematopoietic cell

transplant in adults after CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv.

2019;3(20). doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000593 https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000593 PMid:31648329 PMCid:PMC6849954

- Little

JS, Weiss ZF, Hammond SP. Invasive fungal infections and targeted

therapies in hematological malignancies. Journal of Fungi. 2021;7(12).

doi:10.3390/jof7121058 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7121058 PMid:34947040 PMCid:PMC8706272

- Quattrone

M, Di Pilla A, Pagano L, Fianchi L. Infectious complications during

monoclonal antibodies treatments and cell therapies in Acute

Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23(6).

doi:10.1007/s10238-023-01000-9 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-023-01000-9 PMid:36715833 PMCid:PMC9885910

- Davis

JS, Ferreira D, Paige E, Gedye C, Boyle M. Infectious complications of

biological and small molecule targeted immunomodulatory therapies. Clin

Microbiol Rev. 2020;33(3). doi:10.1128/CMR.00035-19 https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00035-19 PMid:32522746 PMCid:PMC7289788

- Winthrop

KL, Mariette X, Silva JT, Benamu E, Calabrese LH, Dumusc A, Smolen JS,

Aguado JM, Fernández-Ruiz M. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in

Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted

and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Soluble

immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins,

immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clinical Microbiology and

Infection. 2018;24. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002 PMid:29447987

- Lanini

S, Molloy AC, Fine PE, Prentice AG, Ippolito G, Kibbler CC. Risk of

infection in patients with lymphoma receiving rituximab: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2011;9. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-36 https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-36 PMid:21481281 PMCid:PMC3094236

- Biyun

L, Yahui H, Yuanfang L, Xifeng G, Dao W. Risk factors for invasive

fungal infections after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Microbiology and

Infection. 2024;30(5). doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2024.01.005 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2024.01.005 PMid:38280518

- Papanicolaou

GA, Chen M, He N, Martens MJ, Kim S, Batista MV, Bhatt NS, Hematti P,

Hill JA, Liu H, Nathan S, Seftel MD, Sharma A, Waller EK, Wingard JR,

Young JH, Dandoy CE, Perales MA, Chemaly RF, Riches M, Ustun C.

Incidence and Impact of Fungal Infections in Post-Transplantation

Cyclophosphamide-Based Graft-versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis and

Haploidentical Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Center for

International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis. Transplant

Cell Ther. 2024;30(1). doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2023.09.017 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2023.09.017 PMid:37775070 PMCid:PMC10872466

- Lien

MY, Yeh SP, Gau JP, Wang PN, Li SS, Dai MS, Chen TC, Hsieh PY, Chiou

LW, Huang WH, Liu YC; Taiwan Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry

(TBMTR); Ko BS. High rate of invasive fungal infections after non-T

cell-depleted haploidentical allo-HSCT even under antifungal

prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56(7).

doi:10.1038/s41409-021-01260-7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-021-01260-7 PMid:33782547

- Sun

YQ, Xu LP, Liu DH, Zhang XH, Chen YH, Chen H, Ji Y, Wang Y, Han W, Wang

JZ, Wang FR, Liu KY, Huang XJ. The incidence and risk factors of

invasive fungal infection after haploidentical haematopoietic stem cell

transplantation without in vitro T-cell depletion. Clinical

Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(10).

doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03697.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03697.x PMid:22085092

- Salvatore

D, Labopin M, Ruggeri A, Battipaglia G, Ghavamzadeh A, Ciceri F, Blaise

D, Arcese W, Sociè G, Bourhis JH, Van Lint MT, Bruno B, Huynk A,

Santarone S, Deconinck E, Mohty M, Nagler A. Outcomes of hematopoietic

stem cell transplantation from unmanipulated haploidentical versus

matched sibling donor in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first

complete remission with intermediate or high-risk cytogenetics: A study

from the acute leukemia working party of the european society for blood

and marrow transplantation. Haematologica. 2018;103(8).

doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.189258 https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.189258 PMid:29748438 PMCid:PMC6068036

- Fukuda

T, Boeckh M, Guthrie KA, Mattson DK, Owens S, Wald A, Sandmaier BM,

Corey L, Storb RF, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis before allogeneic

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: 10-year experience at a single

transplant center. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

2004;10(7). doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.02.006 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.02.006 PMid:15205670

- Foord

AM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Boeckh MJ, Carpenter PA, Flowers MED, Lee SJ,

Leisenring WM, Mueller BA, Hill JA, Chow EJ. Late infectious

complications in hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: A

population-based study. Blood Adv. 2020;4(7).

doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001470 https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001470 PMid:32227211 PMCid:PMC7160274

- Pagano

L, Maschmeyer G, Lamoth F, Blennow O, Xhaard A, Spadea M, Busca A,

Cordonnier C, Maertens J; ECIL. Primary antifungal prophylaxis in

hematological malignancies. Updated clinical practice guidelines by the

European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL). Leukemia.

Published online April 9, 2025. doi:10.1038/s41375-025-02586-7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02586-7 PMid:40200079 PMCid:PMC12208874

- Ullmann

AJ, Lipton JH, Vesole DH, Chandrasekar P, Langston A, Tarantolo SR,

Greinix H, Morais de Azevedo W, Reddy V, Boparai N, Pedicone L, Patino

H, Durrant S. Posaconazole or Fluconazole for Prophylaxis in Severe

Graft-versus-Host Disease. New England Journal of Medicine.

2007;356(4). doi:10.1056/nejmoa061098 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061098 PMid:17251530

- Yi

WM, Schoeppler KE, Jaeger J, Mueller SW, MacLaren R, Fish DN, Kiser TH.

Voriconazole and posaconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: A

retrospective study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;16(1).

doi:10.1186/s12941-017-0235-8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-017-0235-8 PMid:28893246 PMCid:PMC5594434

- Amigues

I, Cohen N, Chung D, Seo SK, Plescia C, Jakubowski A, Barker J,

Papanicolaou GA. Hepatic Safety of Voriconazole after Allogeneic

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow

Transplantation. 2010;16(1). doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.015 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.015 PMid:20053331 PMCid:PMC3094157

- Suetsugu

K, Muraki S, Fukumoto J, Matsukane R, Mori Y, Hirota T, Miyamoto T,

Egashira N, Akashi K, Ieiri I. Effects of Letermovir and/or

Methylprednisolone Coadministration on Voriconazole Pharmacokinetics in

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Population Pharmacokinetic

Study. Drugs in R and D. 2021;21(4). doi:10.1007/s40268-021-00365-0 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-021-00365-0 PMid:34655050 PMCid:PMC8602551

- Nakashima

T, Inamoto Y, Fukushi Y, Doke Y, Hashimoto H, Fukuda T, Yamaguchi M.

Drug interaction between letermovir and voriconazole after allogeneic

hematopoietic cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2021;113(6).

doi:10.1007/s12185-021-03105-x https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-021-03105-x PMid:33677768

- Lee

E, Lin A, Su Y, Cho C, Seo SK. The Clinical Significance of the

Drug-Drug Interaction between Letermovir and Voriconazole in Stem Cell

Transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther. 2024;30(2).

doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2023.12.629 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2023.12.629

- Marr

KA, Crippa F, Leisenring W, Hoyle M, Boeckh M, Balajee SA, Nichols WG,

Musher B, Corey L. Itraconazole versus fluconazole for prevention of

fungal infections in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell

transplants. Blood. 2004;103(4). doi:10.1182/blood-2003-08-2644 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-08-2644 PMid:14525770

- Menichetti

F, Del Favero A, Martino P, Bucaneve G, Micozzi A, Girmenia C,

Barbabietola G, Pagańo L, Leoni P, Specchia G, Caiozzo A, Raimondi R,

Mandelli F. Itraconazole oral solution as prophylaxis for fungal

infections in neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancies: A

randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial.

Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1999;28(2). doi:10.1086/515129 https://doi.org/10.1086/515129 PMid:10064240

- Stern

A, Su Y, Lee YJ, Seo S, Shaffer B, Tamari R, Gyurkocza B, Barker J,

Bogler Y, Giralt S, Perales MA, Papanicolaou GA. A Single-Center,

Open-Label Trial of Isavuconazole Prophylaxis against Invasive Fungal

Infection in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell

Transplantation: Isavuconazole for Antifungal Prophylaxis following

HCT. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2020;26(6).

doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.02.009 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.02.009 PMid:32088367 PMCid:PMC8210627

- Khatri

AM, Natori Y, Anderson A, Jabr R, Shah SA, Natori A, Chandhok NS,

Komanduri K, Morris MI, Camargo JF, Raja M. Breakthrough invasive

fungal infections on isavuconazole prophylaxis in hematologic

malignancy & hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.

Transplant Infectious Disease. 2023;25(S1). doi:10.1111/tid.14162 https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.14162 PMid:37794708

- van

Burik JA, Ratanatharathorn V, Stepan DE, Miller CB, Lipton JH, Vesole

DH, Bunin N, Wall DA, Hiemenz JW, Satoi Y, Lee JM, Walsh TJ; National

Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group.

Micafungin versus fluconazole for prophylaxis against invasive fungal

infections during neutropenia in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;39(10).

doi:10.1086/422312 https://doi.org/10.1086/422312 PMid:15546073

- Guinea

J. New trends in antifungalantifungal treatment: What is coming up?

Revista Espanola de Quimioterapia. 2023;36.

doi:10.37201/req/s01.14.2023 https://doi.org/10.37201/req/s01.14.2023 PMid:37997874 PMCid:PMC10793560

- Jacobs

SE, Zagaliotis P, Walsh TJ. Novel antifungalantifungal agents in

clinical trials. F1000Res. 2022;10. doi:10.12688/f1000research.28327.2 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.28327.2 PMid:35136573 PMCid:PMC8787557

- Ordaya

EE, Clement J, Vergidis P. The Role of Novel AntifungalsAntifungals in

the Management of Candidiasis: A Clinical Perspective. Mycopathologia.

2023;188(6). doi:10.1007/s11046-023-00759-5 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-023-00759-5 PMid:37470902 PMCid:PMC10687117

- August

BA, Kale-Pradhan PB. Management of invasive candidiasis: A focus on

rezafungin, ibrexafungerp, and fosmanogepix. Pharmacotherapy.

2024;44(6):467-479. doi:10.1002/phar.2926 https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2926 PMid:38721866

- Wingard

JR, Carter SL, Walsh TJ, Kurtzberg J, Small TN, Baden LR, Gersten ID,

Mendizabal AM, Leather HL, Confer DL, Maziarz RT, Stadtmauer EA,

Bolaños-Meade J, Brown J, Dipersio JF, Boeckh M, Marr KA; Blood and

Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network. Randomized, double-blind

trial of fluconazole versus voriconazole for prevention of invasive

fungal infection after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Blood. 2010;116(24). doi:10.1182/blood-2010-02-268151 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-02-268151 PMid:20826719 PMCid:PMC3012532

- Stemler

J, Mellinghoff SC, Khodamoradi Y, Sprute R, Classen AY, Zapke SE,

Hoenigl M, Krause R, Schmidt-Hieber M, Heinz WJ, Klein M, Koehler P,

Liss B, Koldehoff M, Buhl C, Penack O, Maschmeyer G, Schalk E,

Lass-Flörl C, Karthaus M, Ruhnke M, Cornely OA, Teschner D. Primary

prophylaxis of invasive fungal diseases in patients with haematological

malignancies: 2022 update of the recommendations of the Infectious

Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Haematology

and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

2023;78(8). doi:10.1093/jac/dkad143 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkad143 PMid:37311136 PMCid:PMC10393896

- Fontana

L, Perlin DS, Zhao Y, Noble BN, Lewis JS, Strasfeld L, Hakki M.

Isavuconazole prophylaxis in patients with hematologic malignancies and

hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases.

2020;70(5). doi:10.1093/cid/ciz282 https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz282 PMid:30958538 PMCid:PMC7931837

- Bogler

Y, Stern A, Su Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of isavuconazole compared

with voriconazole as primary antifungal prophylaxis in allogeneic

hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2021;59(10).

doi:10.1093/mmy/myab025 https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myab025 PMid:34036319 PMCid:PMC8487767

- Nguyen

MH, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pappas PG, Walsh TJ, Bubalo J, Alexander BD,

Miceli MH, Jiang J, Song Y, Thompson GR 3rd. Real-world Use of

Mold-Active Triazole Prophylaxis in the Prevention of Invasive Fungal

Diseases: Results From a Subgroup Analysis of a Multicenter National

Registry. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(9). doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad424 https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad424 PMid:37674634 PMCid:PMC10478153

- Douglas

AP, Smibert OC, Bajel A, Halliday CL, Lavee O, McMullan B, Yong MK, van

Hal SJ, Chen SC; Australasian Antifungal Guidelines Steering Committee.

Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of invasive

aspergillosis, 2021. Intern Med J. 2021;51(S7). doi:10.1111/imj.15591 https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15591 PMid:34937136

- Boyer

J, Feys S, Zsifkovits I, Hoenigl M, Egger M. Treatment of Invasive

Aspergillosis: How It's Going, Where It's Heading. Mycopathologia.

2023;188(5). doi:10.1007/s11046-023-00727-z https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-023-00727-z PMid:37100963 PMCid:PMC10132806

- Zurl

C, Waller M, Schwameis F, Muhr T, Bauer N, Zollner-Schwetz I, Valentin

T, Meinitzer A, Ullrich E, Wunsch S, Hoenigl M, Grinschgl Y, Prattes J,

Oulhaj A, Krause R. Isavuconazole treatment in a mixed patient cohort

with invasive fungal infections: Outcome, tolerability and clinical

implications of isavuconazole plasma concentrations. Journal of Fungi.

2020;6(2). doi:10.3390/jof6020090 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6020090 PMid:32580296 PMCid:PMC7344482

- Herbrecht

R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern

WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P, Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin RH, Wingard JR,

Stark P, Durand C, Caillot D, Thiel E, Chandrasekar PH, Hodges MR,

Schlamm HT, Troke PF, de Pauw B; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of

the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the

Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus Amphotericin B for

Primary Therapy of Invasive Aspergillosis. New England Journal of

Medicine. 2002;347(6). doi:10.1056/nejmoa020191 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020191 PMid:12167683

- Marr

KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, Rottinghaus ST, Bow EJ, Cornely OA, Heinz

WJ, Jagannatha S, Koh LP, Kontoyiannis DP, Lee DG, Nucci M, Pappas PG,

Slavin MA, Queiroz-Telles F, Selleslag D, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR,

Maertens JA. Combination antifungalantifungal therapy for invasive

aspergillosis a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2).

doi:10.7326/M13-2508 https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-2508 PMid:25599346

- Cornely

OA, Sprute R, Bassetti M, Chen SC, Groll AH, Kurzai O, Lass-Flörl C,

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Revathi G, Santolaya ME,

White PL, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arendrup MC, Baddley J, Barac A,

Ben-Ami R, Brink AJ, Grothe JH, Guinea J, Hagen F, Hochhegger B,

Hoenigl M, Husain S, Jabeen K, Jensen HE, Kanj SS, Koehler P,

Lehrnbecher T, Lewis RE, Meis JF, Nguyen MH, Pana ZD, Rath PM, Reinhold

I, Seidel D, Takazono T, Vinh DC, Zhang SX, Afeltra J, Al-Hatmi AMS,

Arastehfar A, Arikan-Akdagli S, Bongomin F, Carlesse F, Chayakulkeeree

M, Chai LYA, Chamani-Tabriz L, Chiller T, Chowdhary A, Clancy CJ,

Colombo AL, Cortegiani A, Corzo Leon DE, Drgona L, Dudakova A, Farooqi

J, Gago S, Ilkit M, Jenks JD, Klimko N, Krause R, Kumar A, Lagrou K,

Lionakis MS, Lmimouni BE, Mansour MK, Meletiadis J, Mellinghoff SC, Mer

M, Mikulska M, Montravers P, Neoh CF, Ozenci V, Pagano L, Pappas P,

Patterson TF, Puerta-Alcalde P, Rahimli L, Rahn S, Roilides E, Rotstein

C, Ruegamer T, Sabino R, Salmanton-García J, Schwartz IS, Segal E,

Sidharthan N, Singhal T, Sinko J, Soman R, Spec A, Steinmann J, Stemler

J, Taj-Aldeen SJ, Talento AF, Thompson GR 3rd, Toebben C,

Villanueva-Lozano H, Wahyuningsih R, Weinbergerová B, Wiederhold N,

Willinger B, Woo PCY, Zhu LP. Global guideline for the diagnosis and

management of candidiasis: an initiative of the ECMM in cooperation

with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect Dis. Published online February 2025.

doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00749-7 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00749-7 PMid:39956121

- Slavin

MA, Chen YC, Cordonnier C, Cornely OA, Cuenca-Estrella M, Donnelly JP,

Groll AH, Lortholary O, Marty FM, Nucci M, Rex JH, Rijnders BJA,

Thompson GR, Verweij PE, White PL, Hargreaves R, Harvey E, Maertens JA.

When to change treatment of acute invasive aspergillosis: an expert

viewpoint. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2022;77(1).

doi:10.1093/jac/dkab317 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkab317 PMid:34508633 PMCid:PMC8730679

- Almajid

A, Bazroon A, Al-Awami HM, Albarbari H, Alqahtani I, Almutairi R,

Alsuwayj A, Alahmadi F, Aljawad J, Alnimer R, Asiri N, Alajlani S,

Alshelali R, Aljishi Y. Fosmanogepix: The Novel Antifungal Agent's

Comprehensive Review of in Vitro, in Vivo, and Current Insights From

Advancing Clinical Trials. Cureus. Published online April 28, 2024.

doi:10.7759/cureus.59210 https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.59210

- Shaw

KJ, Ibrahim AS. Fosmanogepix: A review of the first-in-class broad

spectrum agent for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. Journal

of Fungi. 2020;6(4). doi:10.3390/jof6040239 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6040239 PMid:33105672 PMCid:PMC7711534

- Feuss

A, Bougnoux ME, Dannaoui E. The Role of Olorofim in the Treatment of

Filamentous Fungal Infections: A Review of In Vitro and In Vivo

Studies. Journal of Fungi. 2024;10(5). doi:10.3390/jof10050345 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10050345 PMid:38786700 PMCid:PMC11121921

- Maertens

JA, Thompson GR 3rd, Spec A, Donovan FM, Hammond SP, Bruns AHW, Rahav

G, Shoham S, Johnson R, Rijnders B, Schaenman J, Hoenigl M, Morrissey

CO, Mehta SR, Heath CH, Koehler P, Paterson DL, Slavin MA, Fortún J,

Nguyen MH, Patterson TF, Uspenskaya O, Van de Veerdonk FL, Verweij PE,

Aoun M, Georgala A, Alexander BD, Chayakulkeeree M, Mehra V, Miceli MH,

Sikka MK, Solé A, Walsh TJ, Aguado JM, Holland SM, Moussa M,

Rautemaa-Richardson R, Bazaz R, Schwartz S, Walsh SR, Plate M,

Yehudai-Ofir D, Brüggemann RJ, Cornely OA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Vazquez

JA, White PL, Cornelissen K, Ross GG, Fitton L, Dane A, Zinzi D, Rex

JH, Chen SC. Olorofim for the treatment of invasive mould infections in

patients with limited or no treatment options: Comparison of interim

results from a Phase 2B open-label study with outcomes in historical

control populations (NCT03583164, FORMULA-OLS, Study 32). Open Forum

Infect Dis. 2022;9(Supplement_2). doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac492.063 https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac492.063 PMCid:PMC9752288

- El

Ayoubi LW, Allaw F, Moussa E, Kanj SS. Ibrexafungerp: A narrative

overview. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2024;6. doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2024.100245

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmicr.2024.100245 PMid:38873590 PMCid:PMC11170096

- Atalla

A, Garnica M, Maiolino A, Nucci M. Risk factors for invasive mold

diseases in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients.

Transplant Infectious Disease. 2015;17(1). doi:10.1111/tid.12328 https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.12328 PMid:25573063

- Sun

Y, Meng F, Han M, Zhang X, Yu L, Huang H, Wu D, Ren H, Wang C, Shen Z,

Ji Y, Huang X. Epidemiology, Management, and Outcome of Invasive Fungal

Disease in Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

in China: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study. Biology of

Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015;21(6).

doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.03.018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.03.018 PMid:25840339

- Fayard

A, Daguenet E, Blaise D, Chevallier P, Labussière H, Berceanu A,

Yakoub-Agha I, Socié G, Charbonnier A, Suarez F, Huynh A, Mercier M,

Bulabois CE, Lioure B, Chantepie S, Beguin Y, Bourhis JH, Malfuson JV,

Clément L, Péffault de la Tour R, Cornillon J. Evaluation of infectious

complications after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation with post-transplant cyclophosphamide following

reduced-intensity and myeloablative conditioning: a study on behalf of

the Francophone Society of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular

Therapy (SFGM-TC). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54(10).

doi:10.1038/s41409-019-0475-7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0475-7 PMid:30770870

- Oltolini

C, Greco R, Galli L, Clerici D, Lorentino F, Xue E, Lupo Stanghellini

MT, Giglio F, Uhr L, Ripa M, Scarpellini P, Bernardi M, Corti C,

Peccatori J, Castagna A, Ciceri F. Infections after Allogenic

Transplant with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide: Impact of Donor HLA

Matching. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2020;26(6).

doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.013 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.013 PMid:32004700

- Souza L, Nouér SA, Morales H, Simões B, Solza C, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in haematologic patients. Mycoses. 2021;64(3). doi:10.1111/myc.13205 https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13205 PMid:33141969